Section Branding

Header Content

'The Three Greats' Of Mexican Modernism Fought Tyranny With Art

Primary Content

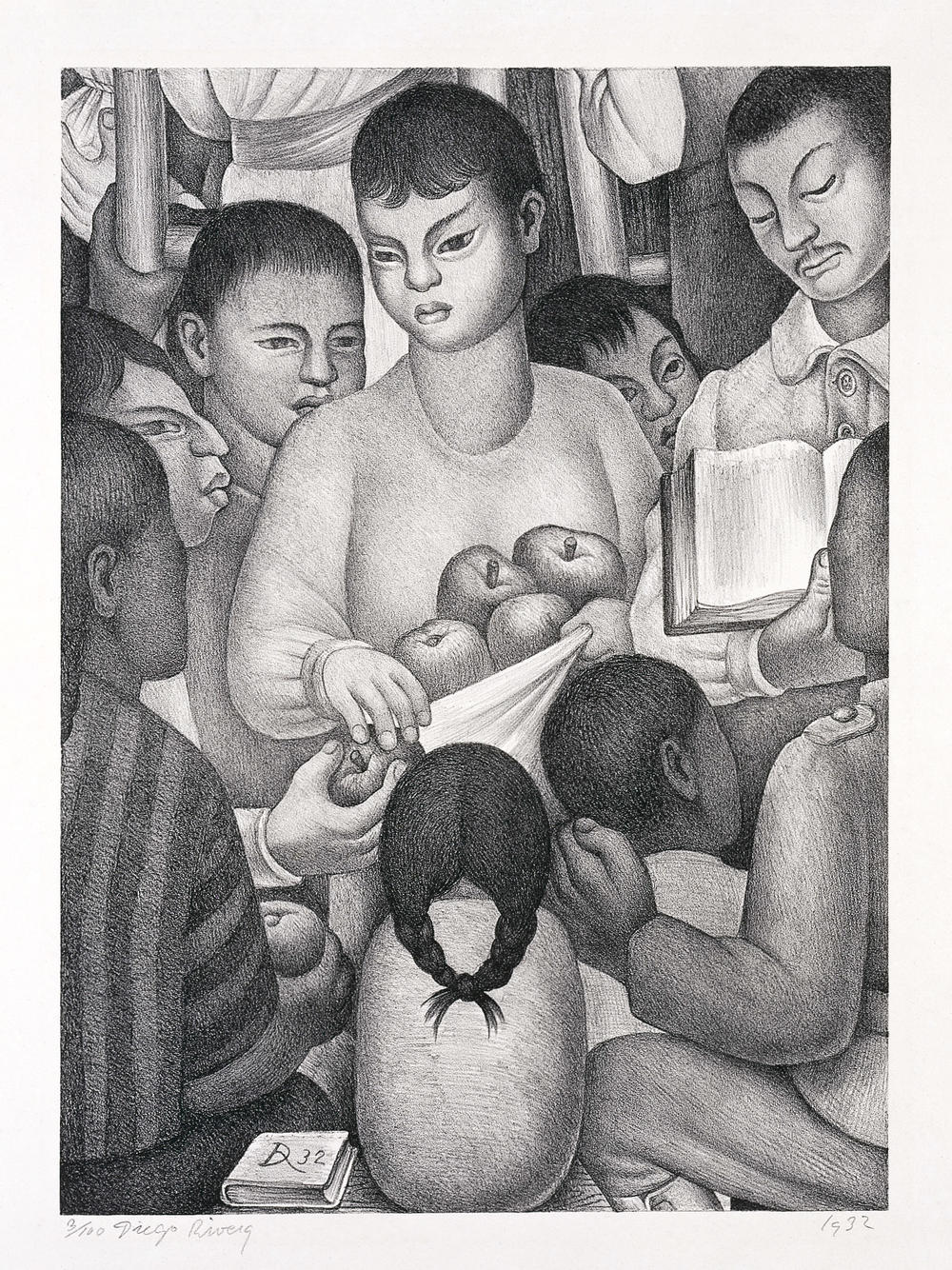

It's such a peaceful image. A woman handing out fruit to a group of young people. But the print is the product of conflict and pain. The bloody, brutal Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) is the theme of an exhibition of prints at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas.

At least a million died, fighting for racial and economic equity. And education. "If you were the wrong color, you were not allowed to go to school," says curator Lyle Williams. Some of Mexico's greatest artists, known as Mexican Modernists, joined the protestors. In the image above, Diego Rivera (Frieda Kahlo's husband) draws Mexicans of all races getting apples along with a revolutionary goal: learning. To Williams, the message is "we work hard. The fruits of our labor are education for all." (Click to see Kahlo's 1931 portrait of herself and Rivera.)

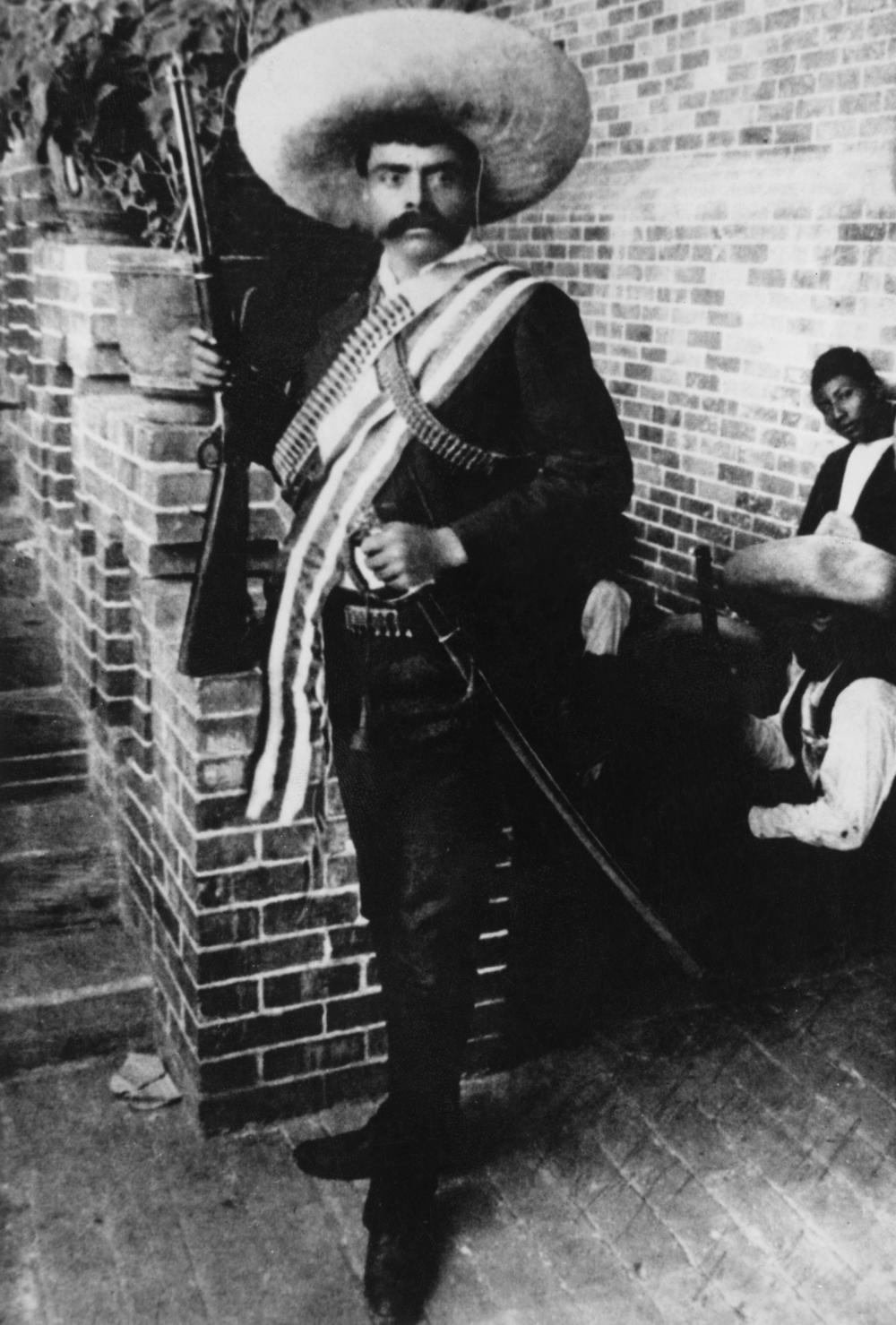

Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, "Los Tres Grandes" (The Three Greats who are the focus of the exhibition) fought tyranny through their art. Revolutionaries like Emiliano Zapata, fought it with guns.

Rivera and Siqueiros drew him in prints. To Rivera, Zapata was noble, heroic. He's dressed in white (so is his horse!). The bandalier across his chest holds, curator Williams' words, "bullets like jewelry." Siqueiros brings Zapata down to earth. He's darker, looks bigger than his small horse. Land reform was Zapata's issue. Only rich families could own land. Farmers had to pay to work it. The Mexican hero fought for redistribution.

Marlon Brando played him in a movie. Brando's Zapata is firmly idealistic in this short clip.

Zapata inspired Brando as he did artists. McNay's curator says the leader was portrayed by loads of artists. "Everybody did him. In fact, to this day people are still creating portraits."

His followers tried to dress like Zapata. The men and women in Orozco's Rear Guard wear sombreros like their hero. And carry guns. The women went off to make revolution with small children on their backs.

Orozco was quite skeptical about war. Curator Lyle Williams says you see it in their slow, sad march. It makes his art more universal. "It represents human suffering, not just the suffering of Mexicans. It speaks to the human condition," Williams says.

The Mexican revolution lasted some 10 years, and many, many families had losses. In the lithograph El Requiem, Orozco shows a family in mourning. Such a quiet quality to the work. Candles. Heads bent. A body inside the dark house. Another universal — mourning. A loved one is gone.

Los Tres Grandes/The Three Greats were all muralists. A poor, illiterate population could learn their country's history and the ideals of the revolution from stories these men painted on walls. The educational murals, commissioned by the post-revolutionary government, made the artists' reputations. People came from all over the world to see them. Small, packable prints, many based on mural details, were a way to reach a wider audience. Art lovers outside of Mexico could own a work like Rivera's Sleep.

Another quiet image. Rivera shows the weight of slumber, the body settling in deeply. The weight of love is here, too. But the toll of revolution is part of the picture. Rivera adopted it from his mural La noche de los pobres (The night of the poor). See the out-stretched hand of the littlest one? Curator Lyle Wiliams says the family has been out all day, begging for money. Now, resting in exhaustion, that daily task still marks their slumber.

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing lively online offerings at museums closed due to COVID-19, or at re-opening museums you may not be able to visit.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.