Caption

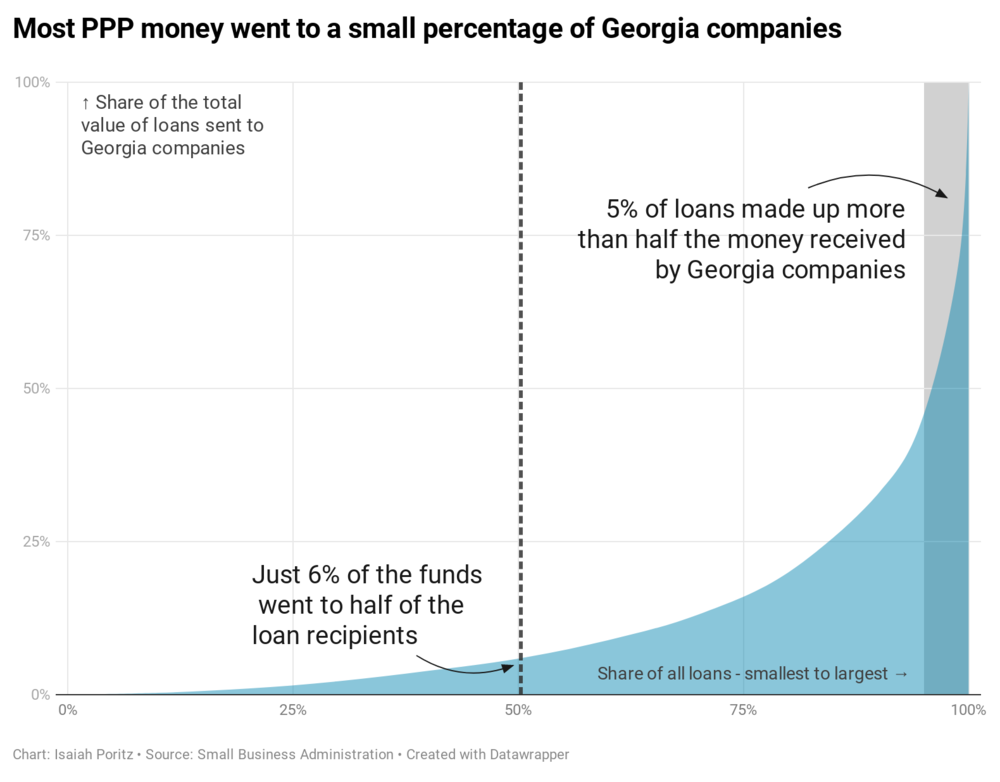

More than half the funds received by Georgia companies as part of the Paycheck Protection Program meant to support small businesses during the pandemic went to large companies, according to newly released data from the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Credit: fca.gov