Section Branding

Header Content

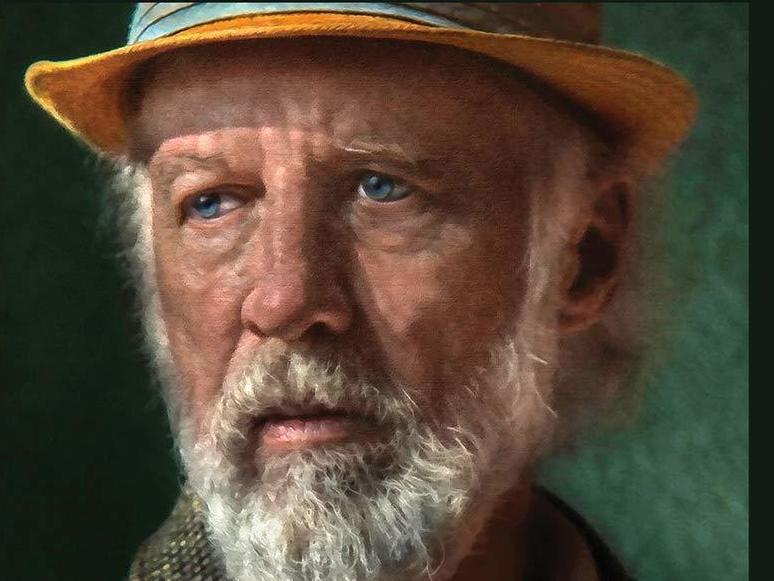

The 'Uncollected Stories' Show Allan Gurganus At His Finest

Primary Content

There aren't too many American authors for whom the publication of a new book is a bona fide literary event, but Allan Gurganus is one of them. The North Carolina author took the book world by storm in 1989 with his debut novel, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, which became a massive bestseller and spawned an Emmy-winning television miniseries adaptation. Only four books followed after that.

Until now. The Uncollected Stories of Allan Gurganus is his first book since 2013, and it's more than worth the wait. The collection is Gurganus at his finest: funny, compassionate, and marked by the author's amazing ability to reflect the lightness — and darkness — in the souls of his fascinating characters.

The collection kicks off with "The Wish for a Good Young Country Doctor," which made something of a splash when it was originally published in The New Yorker last spring. The story is narrated by an antique collector reflecting on his days as an American studies graduate student; he was part of a band of "merry hippie researchers" and "cerebral hucksters" who frequented antique stores in the Midwest, delighting in every kitschy old toy they managed to dig up.

At one store, the student's eye is caught by a 19th-century painting, and he convinces the store's initially belligerent proprietor to tell him about the subject. It turns out to be a portrait of Fredrick M. Petrie, who arrived in a small town called La Verne at the same time as a cholera epidemic. "[T]he doctor was soon the only person brave or fool enough to duck under the quarantine ropes, ignoring warning signs he himself had nailed to doors of those farmhouses worst hit," the store owner explains. Despite the doctor's help, the townspeople turn on him, blaming him for the wave of illnesses. "In La Verne, if we act too kind or smart or interested in much, they'll make us pay. And pay. And pay," the shop owner says.

It's easy to see why the story resonated so much last year with readers who were just weeks into a pandemic of their very own. In 31 pages, Gurganus spotlights the best and worst in America: the selflessness of those who put their own lives in danger to help others, and the inexplicable mean-spiritedness they're too often subjected to in return. It's a story that hits way too close to home, and Gurganus tells it beautifully, with an underlying anger that nonetheless never turns to cynicism.

Much more hopeful is "Unassisted Human Flight," which follows a reporter wrapping up his stint at a small-town North Carolina newspaper with one last big article: a story about an eight-year-old boy who, decades back, was carried by a tornado and left unharmed. The boy, now an engineer in his 40s, initially resists the reporter's entreaties to talk to him, reluctant to revisit the storm that killed his twin brother.

But the reporter persists, and eventually the man agrees to share his story. "But wherever we wind up, in whatever amount, I think we'll exit riding some force to show us out," the engineer tells the reporter. "Death is room-temperature. It has no mass but is a Fact. And nothing's out to torture us except certain other people. No hidden meanness is waiting to trap us."

It's a beautiful story that works chiefly because of Gurganus' gift for writing realistic, but still musical, dialogue. He gets the intonations of Southern speech just right, and never condescends to his small-town characters.

The standout story in the collection is "Fetch," in which a narrator tells the story of witnessing a middle-aged couple taking their Labrador retriever to the beach. The woman appears gravely ill, with her partner helping her walk: "How many months now has he slowed his gait to honor gravity's sudden tax on hers?"

Although the weather is inclement, the man throws a stick into the ocean for the dog to fetch, and it soon finds itself struggling to stay afloat, sending the couple into a panic: "And you soon hear in their torn scraps of sound how they no longer simply tease or coax the animal ashore; theirs have become cries and screams ascending to the pitch of non-believers' prayers."

It's an astounding story (although one that will likely send any dog lovers reading it into a panic attack); Gurganus proves to be a master of pacing, recounting the dog's struggle in exacting, finely observed detail. Remarkably, he tells the story with no dialogue; the narrator only sees the couple communicating in gestures — it's a technique that somehow manages to amp up the tension of the story while still making clear the love the couple have for each other and for their beloved pet.

And like all the stories in the collection, it's full of Gurganus' deep-seated compassion and fascination with — and love for — humanity. This is a remarkable book, and it proves once again why Gurganus is one of the country's most talented and imaginative writers. Coming after a year where nothing went right, and the world was forced to realize that things might not work out in the end, it's a hopeful tonic. As Gurganus writes, "We grant ourselves so little daily hope. Meanwhile, barely noticing, we've already managed wonders."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content