Caption

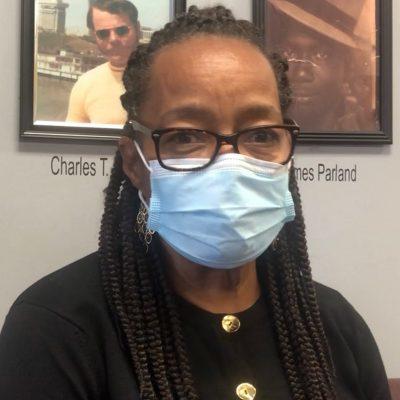

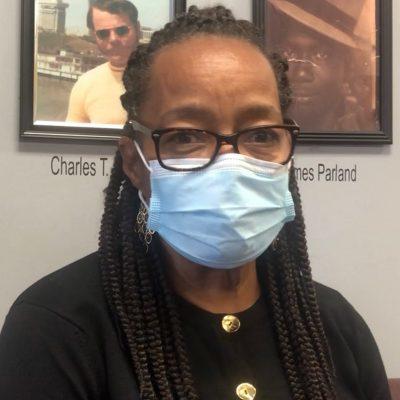

Hattie Fogle was 19 when she went to work at Thiokol. It’s taken decades for her to be able to talk about the explosion.

Credit: Laura Corley/The Current

Laura Corley, The Current

There are no Purple Hearts or Medals of Honor for the dozens killed and maimed while fighting the Vietnam War from Woodbine a half century ago.

Those killed and maimed weren’t wearing uniforms like the thousands of Georgians deployed aboard during the war. They were mostly poor, Black women who worked for $1.65 an hour assembling trip flares for the U.S. Army at the Thiokol Chemical Corp. munitions plant.

People were overjoyed at the prospects of a full-time job, a rare find for women and Black people in Coastal Georgia at the time.

Hattie Fogle was 19 when she went to work at Thiokol. It’s taken decades for her to be able to talk about the explosion.

Workers like Hattie Fogle, who was a 19-year-old single mother when she went to work for Thiokol, didn’t know just how dangerous the job was until that gruesome day 50 years ago when a fire sparked an explosion so powerful that it shook the Earth for miles around.

The blast killed 29 of her coworkers including her brother and a sister-in-law. It maimed her cousin who lost an arm and was badly burned. It scarred the hundreds of others who survived.

“I can still feel a pain from it,” Fogle said, adding that it’s taken years to be able to talk about the catastrophe without weeping. “I’m able to voice it and not break down. You’ve got people that can’t tell the stories for themselves, so you have to be the one.”

The 50th anniversary ceremony honoring victims of the Thiokol explosion is set for 10 a.m. Wednesday at Chris Gilman Stadium in Kingsland. It is being organized by the Thiokol Memorial Project, a museum dedicated to one of America’s worst industrial accidents, but one that is largely unknown and unrecognized even in Georgia.

Ongoing nightmares about charred corpses, the physical agony of burn scars and missing limbs plus an exhausting 17-year court battle with the company and U.S. government kept the survivors from speaking much about the traumas they have endured. Yet as Georgia starts a new reckoning with racial injustice, the survivors have found their voice. They want their sacrifice on behalf of the war effort and workers’ rights finally honored after decades in which their stories and their struggles have been left out of history books.

“These people were poor. Many of them were people of color. Twenty-one women was killed that day. How could you miss that after all these years? Those children grew up without their mothers,” said Jannie Everette, whose 81-year-old mother is one of the Thiokol survivors. She has dedicated the past six years of her life to the small museum in downtown Kingsland to ensure that Georgians don’t forget the catastrophe.

Residents of Coastal Georgia remember 1964 as the year Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. won the Nobel Peace Prize, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. It was also the year the U.S. leader and Georgia Gov. Carl Sanders visited Woodbine for the grand opening of what reporters at the time called the “first Georgia space plant.”

Visitors to Thiokol in 1964 look down into depths of giant static firing pit which is 120 feet deep. The pit was originally used to test rockets for space travel.

The land, some 7,500 acres on Horse Pen Bluff, was a plantation before the development. The site offered deep water access to Cape Canaveral in Florida where the government was starting its space program. Thiokol was part of that endeavor with a $23 million contract to make solid fuel rocket boosters for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

By 1969, communities like Woodbine had not seen much of the promised changes that the Civil Rights Act was meant to bestow. Land was being cleared to make way for Interstate 95. Good jobs were in short supply and Thiokol just began to hire women.

The Vietnam War was a full-blown conflict, chewing up hundreds of American lives each month. So when Thiokol won a contract to supply the U.S. Army with 750,000 trip flares and CS-gas at the Woodbine plant, Fogle remembers the community rippling with excitement about new, full-time opportunities, especially for women. Until the plant opened, she and her kin had been traveling to Brunswick for piecemeal work at King Shrimp. Now, they had a chance to earn a paycheck and help their country.

“It was an opportunity for women to do better,” Fogle said. “I could go to work, come home and provide for my child. There were times when we went to the shrimp factory and if the shrimps weren’t there in my department, I went home early. So there was not a guaranteed 40-hour paycheck.”

Fogle went to work each day along with her brother, sister-in-law and two cousins. Each worked on the factory line where workers transformed raw explosive material into the deadly munitions that U.S. infantrymen would use to defend their own lives.

Fogle’s specialty was putting the safety pins in the trip flares, a job that required using an air gun with a foot pump to insert the pin. One day, that air gun malfunctioned.

“The trip flare blew up in my hand and they had to catch me because I just, because we were told, If somebody hollers, ‘Fire!’ and you hear ‘Boom,’ run. Get out and they’ll tell you when to come back in,” she said. “But when you’ve got something in your hand and it goes off, the first thing I did was start running. … We’d done that many times.”

Survivors remember Thiokol didn’t offer much in the way of safety training. They largely left matters up to the workers. So when sparks would fly, the women working the line almost reflexively evacuated while their male coworkers rushed in to extinguish the flames.

They all returned to work each time, treating the risk as part of the job.

“It was after the explosion that we found out just how dangerous the stuff we were working with was,” Fogle said. “Thiokol didn’t know the danger. The workers didn’t know.”

What Thiokol told its employees is what the U.S. Army had told the company: The magnesium trip flares contained a Class 2 explosive, a flammable material. Only later, when the factory had been reduced to cinders, did it become known that the army had failed to inform the company that the material had been upgraded to a Class 7 explosive, the most dangerous classification. The classifications determine how the materials are handled and stored.

The memo about the upgraded classification never made it to anyone at Thiokol. It had been written on a paper note that was discovered in a bottom drawer of an Army officer’s desk sometime after the disaster.

“The thing that really did it was, this guy just didn’t pass it on,” said Arnold Young, a lawyer for HunterMaclean who sat in on the federal trials on behalf of a company that was not part of the lawsuit. “That’s what caused the disaster … It’s like everything else in the world: somebody just simply screwed up.”

Had Thiokol received the memo, it would have had to make many changes in the way it stored and handled the materials, a key cause of the explosion.

Fires and evacuations were so routine at Thiokol, that when a small flame was spotted on the assembly line in Building M-132 shortly before 11 a.m. on Feb. 3, 1971, many employees on the factory’s morning shift left their stations, but didn’t move very far away from the building.

That mistake would prove fatal.

The flames quickly spread to ignition pellets used to build the munitions and then to the next door curing room where about 8,000 pounds of illuminants made of magnesium and sodium nitrate were being stored. Also in the curing room were 56,322 candles containing approximately 0.3 pounds of illuminant each; 18,472 ignition pellets, and 100 pounds of first fire and intermediate mix, according to court records.

Three to four minutes after the fire broke out, the building exploded with such magnitude that witnesses reported seeing a mushroom cloud from miles away.

The Earth shook up and down the Georgia-Florida coastline.

Fireman search for bodies in twisted wreckage of the Thiokol plant in Woodbine on Feb. 4, 1971.

At the time, few towns in America had what we now know as Emergency Services, but Jacksonville Fire Department was among the first in the country to train its staff on basic life-saving measures like CPR. It sprung into action to help save lives in the Thiokol blaze.

Meanwhile, workers who had cars at the plant drove the injured and dead to 14 different hospitals. Area funeral homes sent hearses to use as ambulances.

Interstate 95 had yet to be completed between Savannah and Jacksonville, and the convoy of vehicles had to traverse the dirt-packed Highway 17 to reach the plant and ferry the wounded to towns in Florida and as far away as Savannah.

More than 600 people from 16 municipalities along with the U.S. Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard responded to the emergency.

Fogle had worked the night shift at Building M-132, and was at home at the time of the explosion. The scenes of the aftermath she described witnessing were akin to a soldier’s trek across a battlefield.

Bodies shrouded with white sheets were laid out in a row at Gilman Hospital in St. Mary’s. Her cousin, Flossie Massey McVeigh, had been burned beyond recognition. Some of her coworkers writhed in agony, some missing limbs.

Her sister-in-law, Betty R. Dawson Burch, also was killed in the explosion.

Her brother, Charles Burch, escaped the plant with their uncle. But then he ran back to the burning building to search for his wife. When the fire had been extinguished, their uncle identified Charles’ corpse by his shoes. His body had been trapped under a fallen beam. The young man had started working only a week earlier and had not even drawn a paycheck.

Fogle said she finds peace in knowing some efforts are being made to remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

“They were doing their civil duty,” she said. “In every army, everybody has a part to play or a part to do. They were actually – we were actually – just doing our part.”

The days and months after the explosion are a blur of pain and suffering for the survivors.

The families of Woodbine were left alone to bury their loved ones and nurse their relatives’ horrific injuries. Few had any health insurance. The wounded had no way to continue earning a living.

The company resumed operations five months after the explosion while some survivors remained in hospital.

Cars lie smashed outside Thiokol Plant (left) and building is destroyed after powerful explosion and fire; debris, charred equipment shown inside the structure.

Later that year, lawyers came to town promising to do right by the workers. They filed a lawsuit against Thiokol on behalf of Flossie Massey and other Thiokol employees, dependents of Thiokol employees or next-of-kin, seeking $550 million in damages.

That kicked off a 17-year legal drama that eventually led to changes in America’s tort reform law, but did little to tamp the raw pain and sense of injustice among the Woodbine families.

The cases started in 1974, but it took three years for Savannah Judge Alexander Lawrence, to issue a ruling. Thiokol and the U.S. government shared liability for the deaths and maiming of the workers, but Thiokol’s payments would be capped by the state’s workmen’s compensation law. The company’s insurance paid out the survivors of the dead factory workers.

The government fought the ruling in appeals courts for the next five years.

Not all the families signed onto the lawsuits. Both them, and the plaintiffs, struggled with debt, and with the crushing realization that the world didn’t care about what happened to them and their community. National events had moved on.

Then came the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger explosion. Thiokol, which had sold off the plant in Kingsland, had pivoted its focus to the U.S. space program. The company, then known as Morton Thiokol Inc., had engineered the rocket booster which caused the fireball above Cape Canaveral.

In the national uproar after that disaster, the company reached settlements with families of the four dead Challenger astronauts within a year. It paid $4,641,000 to settle the claims and the government paid $3,094,000.

The adverse publicity about the company gave leverage to the lawyers of the Woodbine families in their settlement talks. Finally, the law suits ended with roughly $20 million paid out to survivors. Like in most tort cases, 25% of the total went to the lawyers.

Those workers who fought for compensation received varied settlement amounts. Some more grievous injured won six-figure payouts. Others, only tens of thousands of dollars. That’s despite not being able to work again after the explosion.

Many of the plant workers, however, received no compensation.

In the aftermath of the explosion, more than 300 of Thiokol’s 500 workers went back to their jobs. They didn’t join the lawsuits because they needed a way to make a living immediately, said Phyllis Rhone and Emma Gibbs, one of the first workers hired by Thiokol in 1969.

Emma Gibbs, 76, recalls the explosion Feb. 3, 1971, at Thiokol Chemical Corp. munitions plant in Woodbine, Georgia. Twenty-nine people were killed and more than 50 were injured. Gibbs was working at the plant there on Horse Shoe Bluff, making trip flares for U.S. Army troops to use in the Vietnam War. The site is now where Camden Spaceport is planned.

“The war was still going on so we kept making things for them,” said Gibbs, who is now 76. “I didn’t have nowhere else to go and I had some children I had to take care of.”

Gibbs recalled the fear she and her coworkers felt upon returning.

“It was kind of eerie,” she said. “It was scary, because after that you best not even drop a pin on the floor because everybody would go run.”

Rhone, who was a single mother, said her aunt, Celia A. Alberta, was hurt in the explosion and died of her injuries days after. She went back to the factory floor anyway.

“You do what you have to do,” Rhone said. “You just don’t think about it.”

Fogle said her mother forbade her from returning to work for Thiokol. She got a job at the Camden County High School cafeteria.

Fogle’s parents sued on behalf of her brother, but both died by the time the litigation ended. The compensation was divided among the siblings.

Her other brother, Louis Burch, sued on behalf of his wife, Betty R. Dawson Burch. Their son, Tony Burch, was just 8 months old when she was killed in the explosion. He was 17 by the time the lawsuit was settled.

Many victims and their families were so consumed by grief and trauma they were unable to manage their daily lives. Neither the company, nor any other government agency, offered the Woodbine families any counseling.

“If we would have had the help we needed to get through that, to help process the grief, it would have been a lot better for a lot of people,” Fogle said.

Fogle stayed silent about her trauma for decades. So did her neighbor, McVeigh, who wakes up at night in terror reliving the pain of being burned alive.

Everette, the head of the museum, was in high school at the time of the explosion. She was among the few residents of Woodbine who had a chance to escape the horrors of the past.

When she graduated, she joined the Army and then made a career working for the Department of Energy in Washington, D.C.

Jannie Everette at the Thiokol Memorial Project museum in Kingsland.

Everette didn’t think about the explosion every day, unlike her mother, Lucille Washington, who suffered permanent hearing damage, scars on her face and arms, and chronic back pain from her injuries sustained at the Thiokol plant.

Everette’s life changed, though, when her mother traveled from Woodbine to her house in Maryland, and from the guest room she overheard her mother crying in agony.

“I pushed the door (open), and she was down on her knees, and she was saying, ‘Oh, Lord.’ ” Everette recalled. “I said, ‘You want me to take you to the hospital?’ She said, ‘No, no, no.’ She said that all of her coworkers, ‘they’ve been killed and hurt and nobody cared.’”

Thiokol Memorial Project’s Thiokol Memorial Museum in downtown Kingsland.

After retiring from her government job in 2014, Everette moved back home to Woodbine. Since then, she founded the nonprofit Thiokol Memorial Project and dedicated her life to honoring the dead and the survivors of the explosion.

She championed efforts to have memorial markers installed at the former site of the plant on Horse Pen Bluff.

She opened a museum in downtown Kingsland where visitors can see artifacts, pictures, articles, video exhibits.

In 2018, she led lobbying efforts at the Georgia state capitol to erect a sign at Exit 7 on Interstate 95, at Harriet’s Bluff Road that reads, “Patriots of Thiokol Memorial Interchange.”

Still, Thiokol remains a little-known part of state and local history.

The explosion didn’t appear on the Camden County history page on the New Georgia Encyclopedia in its 2018 update. The encyclopedia was created and is maintained by the Georgia Humanities Council in partnership with the University of Georgia Press, the University System of Georgia/GALILEO, and the Office of the Governor.

Patriots of Thiokol Memorial Interchange at I-95 and Harriet’s Bluff Road.

European settlers, plantation owners and military history are among topics covered in a 500-page book about Camden County’s history written in 1994. A third of a page is devoted to Thiokol’s $10 million dollar investment to build a plant here in 1961. Only two sentences are devoted to the explosion.

Fogle said she assumed that horrific day at Thiokol was largely missing from history because, “being a small town like this, maybe people just overlooked or, even they could have felt that these people were not worthy. I can’t say whose fault it is that it fell between the cracks.”

Rhone said she shares some of the blame.

“Even some of our kid’s kids don’t know anything about this,” she said. “We bear some of the responsibilities because we don’t tell them about this, you know, and it should be a part of the history. … This happened right here.”

Everette said that mass tort litigation was rewritten as a result of the disaster at Thiokol.

“Nobody knew how to value the loss of life,” Everette said of the compensation suits from Thiokol workers. “The same legislation that was used for Thiokol was used for 9/11 victims. People didn’t like it, but that’s what the law was.”

The 50th anniversary ceremony honoring victims of the Thiokol explosion is supported by the Georgia Council of the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. It will include a flag presentation and choral performances.

The Current will livestream the event from its Facebook page.

Public schools around Camden County will hold a moment of silence for the victims at the precise time of the blast. Rep. Earl “Buddy” Carter is scheduled to send one of his staff members to the ceremony organized by Everette this year. But the museum director Everette says normally she has a problem maintaining the interest of local elected officials.

That is particularly important since one of her goals is to recognize the survivors with a Congressional Medals of Honor for the work they did on behalf of the Vietnam War.

Everette said former U.S. Sen. David Perdue agreed to help with that effort. In the past, however, she said Carter had been noncommittal, despite emails to his office as far back as 2016 about the medals.

Carter told The Current that he has helped the Thiokol Memorial Project in its efforts to designate the museum as part of the National Parks Service. However, he did not remember any mention of the medals. When he spoke with The Current, he said be glad to help achieve that goal. “We’ll be working on it,” he said.

Everette has not reached out to Georgia’s newly elected senators, Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff.

Late last week, Everette learned the U.S. Air Force had denied her request for a fly over during the 50th anniversary ceremony. The rejection came in the form of a call from a Utah area code followed by an email from the Virginia-based Aviation Support Branch.

“The official guidance for 2020 allows the Air Force to provide aerial event support for air shows, national-level sporting events and events held in honor of the five patriotic holidays,” according to the email. “Patriotic holiday events must have an established military presence, such as a military speaker, military formation, Honor/Color Guard presentation, the National Anthem, etc. Unfortunately, under these provisions, your event is ineligible.”

The denial came as a blow to Fogle and the survivors, who think back to their and their co-workers’ sacrifices as just as meaningful as the men and women who deployed to fight for their county.

“Every life matters and these people on this wall paid the ultimate sacrifice,” Fogle said, referring to the portraits in the museum who died at Thiokol. “They gave their life. They had no idea the danger of what they was working with, but they went to work every day and they gave a good long hard day’s work and they did it for the betterment of their family.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, providing non-partisan, solutions-based investigative journalism without bias, fear or favor with clear focus on issues affecting Savannah and Coastal Georgia.