Section Branding

Header Content

Timeline: What Trump Told Supporters For Months Before They Attacked

Primary Content

This week's Senate impeachment trial for former President Donald Trump centers on his role in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, when thousands of rioters disrupted Congress, killing and injuring Capitol police officers and others in the process. The crowd had come directly from an event where Trump had spoken to them.

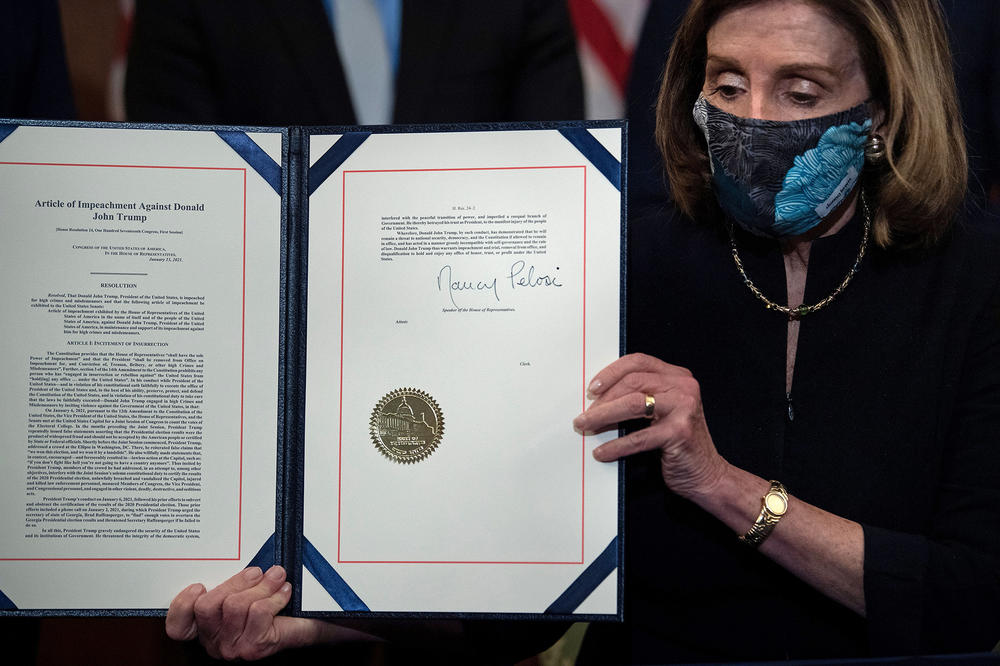

But the acts at issue stretch back much earlier than Jan. 6. In a legal brief filed last week, prosecutors from the House of Representatives, which impeached Trump in January, specified actions by the president many months before that day. In the trial, set to begin on Tuesday, the impeachment managers will seek to prove that his actions directly incited the insurrection.

The ex-president's lawyers argue that Trump "did not direct anyone to commit lawless actions" and that his comments on Jan. 6 are protected by the First Amendment. In its own brief filed Monday, Trump's defense team also claims the Senate does not have the right to try a president who has left office — a point many constitutional experts disagree with.

The defense claims that Trump's months of constant comments about election fraud before Jan. 6 "were, at most, only abstract discussions that never advocated for physical force."

Still, the record shows at least eight months of incendiary statements leading up to the violence at the Capitol. Here, according to an NPR review, are some key moments.

Apr. 7, 2020: Attacking the election

Trump made one of his first false claims about the security of mail-in ballots.

"Mail ballots are a very dangerous thing for this country, because they're cheaters," he said. "They go and collect them. They're fraudulent in many cases." In reality, mail-in ballots had been used safely by several states for years, with insignificant instances of fraud. The president himself had voted by mail.

April 7 was a momentous day: the date of Wisconsin's presidential primary. Voters were standing in long lines despite the risk of coronavirus. The state Supreme Court had rejected an effort to extend absentee balloting in the pandemic. Other states were debating vote-by-mail measures for the fall election.

June 25: The chorus

Attorney General William Barr followed Trump's lead. He questioned mail-in ballots, raising the specter of counterfeiting — even though he acknowledged in an NPR interview that his concern had no basis in fact.

"Did you have evidence to raise that specific concern?" he was asked.

"No," Barr replied. "It's obvious."

July 19: "I'm not going to just say yes"

By midsummer, Trump was consistently behind in polling against Democrat Joe Biden. The president told Fox News that "mail-in voting is going to rig the election."

Interviewer Chris Wallace responded, "Are you suggesting that you might not accept the results of the election?"

"I have to see," Trump replied.

Wallace tried again. "Can you give a direct answer: Will you accept the election?"

Trump replied: "I'm not going to just say yes. I'm not going to say no."

Aug. 19: "I appreciate" people who believed a conspiracy theory

At a White House briefing, a reporter asked Trump what he thought of the QAnon movement, adherents of an elaborate, false conspiracy theory. The FBI had previously warned that this conspiracy would likely cause people to "carry out criminal or violent acts."

Trump replied: "Well, I don't know much about the movement other than I understand they like me very much, which I appreciate."

Sept. 29: "Stand back and stand by"

At a presidential debate, moderator Chris Wallace asked Trump if he was willing to denounce white supremacists. Instead, he told the Proud Boys — which the Southern Poverty Law Center has classified as a hate group associated with white nationalism — to "stand back and stand by."

Ryan Goodman, editor of the website Just Security, tracked the group's online reaction as part of research for its own timeline of the attack. " 'Stand by' is thought of as a signal to them that's actually quite positive," and they vowed to stand by for orders from him, Goodman said.

Trump later said he meant for them to "stand down."

Nov. 3: Election Night

The president was widely expected to claim victory on election night, when he might be leading in early ballot counts. At a White House event at 2:30 a.m. ET as ballot counting continued, including in crucial swing states, he falsely claimed victory: "We were getting ready to win this election. Frankly, we did win this election."

In the days that followed, Trump supporters mobbed ballot-counting sites.

Nov. 7: Biden wins

News networks, including NPR, accurately reported that Joe Biden had won the election, based on state and local vote tallies across the nation. Rather than acknowledge the result, Trump's allies launched dozens of baseless lawsuits, often over minor issues that would not have changed the election even if true.

Nov. 9: Republicans offer cover

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell did not repeat the president's false claims of fraud — but still defended the president's refusal to concede: "A few legal inquiries from the president do not exactly spell the end of the republic."

He was speaking on the Senate floor, where rioters who believed the election falsehoods would be standing less than two months later.

Nov. 19: The hair dye incident

In court, Trump's lawyers, including Rudolph Giuliani, pointedly told judges that he and his team were not alleging fraud; they could be punished for lying in court. Outside courtrooms, it was different. Lawyers Giuliani and Sidney Powell held a press conference at the offices of the Republican National Committee.

"I know crimes," GIuliani said. "I can smell them. You don't have to smell this one. I can prove it to you 18 different ways," though he never did.

What seemed like hair dye ran down his face as Powell spun out an elaborate theory linking ballot fraud to the long-deceased Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez.

Dec. 1: The warning

Gabriel Sterling, a Georgia election official, made an appeal directly to the president at an Atlanta news conference: "Stop inspiring people to commit potential acts of violence. Someone's going to get hurt. Someone's going to get shot. Someone's going to get killed."

Dec. 14: The Electoral College votes

Presidential electors met in their state capitals and cast their votes for president. A last-ditch lawsuit to disrupt the count, supported by numerous Republican state attorneys general, had been dismissed by the Supreme Court.

Dec. 15: An unsuccessful effort to rein in Trump

McConnell signaled that the time for the "few legal inquiries" had passed. "Today I want to congratulate President-elect Joe Biden," McConnell said.

Dec. 19: "Will be wild!"

Trump tweeted about the upcoming joint session of Congress, where the electoral votes submitted by the states were to be formally counted. "Big protests in D.C. on January 6. Be there. Will be wild!" It was one of several times he promoted a rally his allies were organizing.

Dec. 30: The objection

Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley announced he would object to the certification of the election on Jan. 6. Republicans in the House had already indicated they would object, but it was necessary for at least one senator to join House members to force debate; Hawley's move assured this.

Jan. 2, 2021: The phone call

Trump phoned Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, asking him to change the state's vote total by just enough votes for Trump to prevail by a single vote. "There's nothing wrong with saying that, you know, um, that you've recalculated." NPR and others reported the call the next day.

Raffensperger stuck with the accurate results.

Also on Jan. 2, before the call was public, the Proud Boys announced that they would attend the Jan. 6 protest.

Ted Cruz and other senators released a statement saying they would join Hawley in raising objections to the vote count on Jan. 6.

Jan. 4: The campaign speech

In a failing effort to win two Senate seats for his party in Georgia, the defeated president talked extensively about his false claims of fraud and said he would "fight like hell."

Jan. 6: Midday

As Congress began formally counting the Electoral College votes, the president, his lawyer and other allies addressed a crowd that included Proud Boys, assorted extremist groups and numerous people wearing QAnon paraphernalia.

"Let's have a trial by combat!" Giuliani proclaimed.

"You'll never take back our country with weakness," Trump said. "You have to show strength and you have to be strong." After a brief mention of peaceful protest, Trump released a crowd that he had been priming with lies for most of a year, and sent them toward the Capitol.

2:24 p.m.

Trump issued a tweet denouncing then-Vice President Pence, who was overseeing the vote count in the Capitol. Pence had declined Trump's demand that he disrupt the count, insisting on following his duty under the Constitution.

Immediately afterward, "The crowd goes wild about calling Pence a traitor," said Ryan Goodman of Just Security. Goodman's website compiled time-stamped video of a rioter inside the Capitol shouting on a phone: "Can I speak to Pelosi? Yeah, we're coming, b****. Oh, Mike Pence? We're coming for you too you f****** traitor."

"Bring out Pence," others chanted.

Robert Pape, who studies political violence at the University of Chicago, says that numerous rioters told reporters at the time, and the FBI afterward, why they had attacked: They believed Trump told them to.

4:17 p.m.

After lawmakers appealed to Trump to call off the attackers, Trump eventually released a video that repeated his election claims, but also called for peace: "So go home. We love you. You're very special."

Rioters followed the president's instructions and began to disperse. Congress eventually reconvened that night and formally certified Biden's election.

6:01 p.m.

In one of his last tweets before his account was removed from Twitter, the defeated president appeared to justify and celebrate the attack: "These are the things and events that happen," when what he falsely called an election victory is stolen. "Go home with love and in peace, remember this day forever!"

It would not be until a week later, the day the House impeached him, that Trump delivered an unequivocal denouncement of the attack.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.