Caption

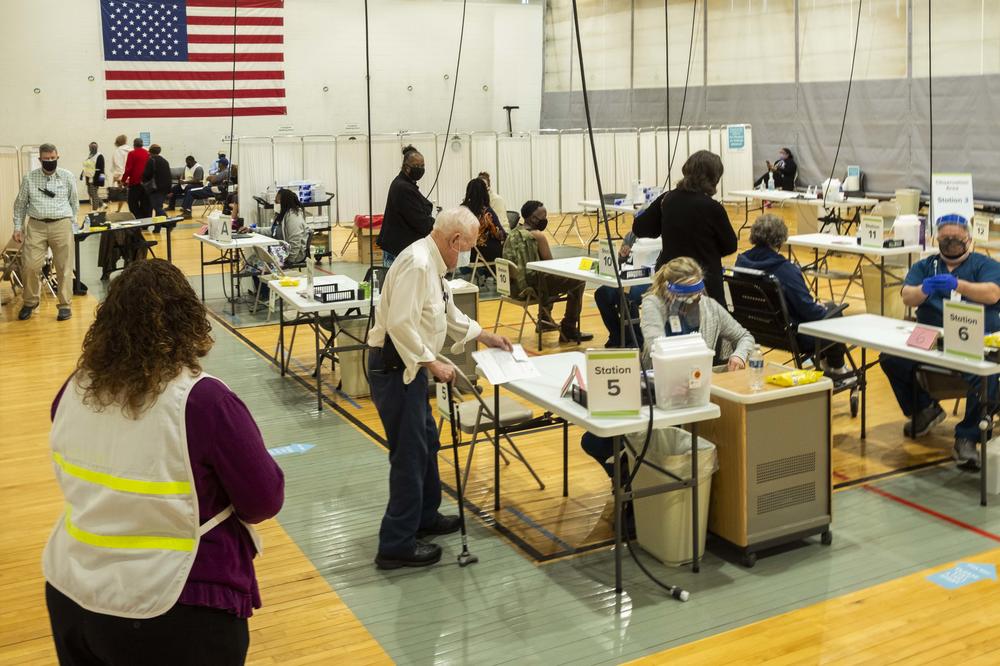

Patients receive doses at the vaccination site in the employee fitness center at Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital in Albany recently.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

|Updated: March 9, 2021 1:53 PM

There is a pair of vaccination machines in Albany, Ga.

The first one is in the employee gym at Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital. There, people run through the COVID-19 vaccination process with assembly-line efficiency.

A beep at the door signals a temperature check, then clerical workers with computer tablets check people in before the main event: a jab in the arm on the basketball court, where an enormous American flag is pinned to the wall.

This scene repeats about 900 times a day.

Compare that scene to a year ago, when the hospital had just recorded its first cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. By the end of March 2020, there were 490 cases in surrounding Dougherty County. And so began one of the first COVID surges in the nation. For a time, Albany was a global COVID-19 hotspot.

Along the way, the city taught the bitter lesson that COVID-19 disproportionately kills Black people. Statistics kept by Phoebe Putney show that around 75% of the almost 300 deaths by COVID in Dougherty County were of Black people.

Will Peterson is the vice president of operations at Phoebe Putney. He said when it came time for the vaccine, these memories loomed large in the community.

“You know, there were so many of us that were just entrenched in this thing for so long that, I mean, you would just wake up some mornings and just wonder: ‘Was it real?’” Peterson said. “You know, ‘Was it a dream?’”

So the hospital prepared. First, it got freezers together for vaccine storage as early as last August. Then as a dry run for quick, fast COVID vaccination, Peterson said the hospital compressed its annual flu vaccine administration, a process that usually takes two months for 5,000 doses, into only two weeks.

“It's also a community that was just waiting for that weapon, waiting for that response,” Peterson said. “You know, waiting for that solution. To do whatever they could do to get back to some sense of normalcy.”

So far the vaccine push in Albany and in southwest Georgia in general has been successful, at least by the standards of the U.S. vaccine rollout. If the region were a U.S. state, it would land near the top of CDC vaccination rankings. CDC data puts Georgia at large at the bottom of those rankings.

Patients receive doses at the vaccination site in the employee fitness center at Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital in Albany recently.

But the relative success comes with a big caveat.

In this majority Black community, where more than 75% of COVID deaths have been among Black people, Black people are being vaccinated half as often as white people. This echoes trends statewide.

The second vaccination machine in Albany is about four miles away from Phoebe Putney, near the airport on the south side of town. This one, staffed by FEMA and the Georgia National Guard, is aimed at getting doses to the most vulnerable people.

On a recent Thursday, an amiable woman in a blue FEMA vest checked people in from their cars.

“Oh my God, you look fabulous, darling!” she exclaimed after a woman confirmed she was old enough for the vaccine. “We can process you like ‘Boom!’ We got nurses waiting with the shots.”

The nurses may have been the only ones waiting. The line of cars in the drive-through site was short despite the acres of blacktop set aside for what was expected to be snarled traffic.

A staffer from FEMA checks people in for COVID-19 vaccination at the mass vaccination site in Albany recently.

It turned out the site was only dosing out about a quarter of what the state intended, while three other mass vaccination sites in the state were having no trouble administering their allotments. So the state moved doses to the most populous region where supply was limited.

“We've actually had Department of Public Safety helicopters come in, fly those doses that would have gone bad on to Atlanta so that they could be used,” Georgia Emergency Management Agency spokesperson Lisa Rodriguez-Presley said.

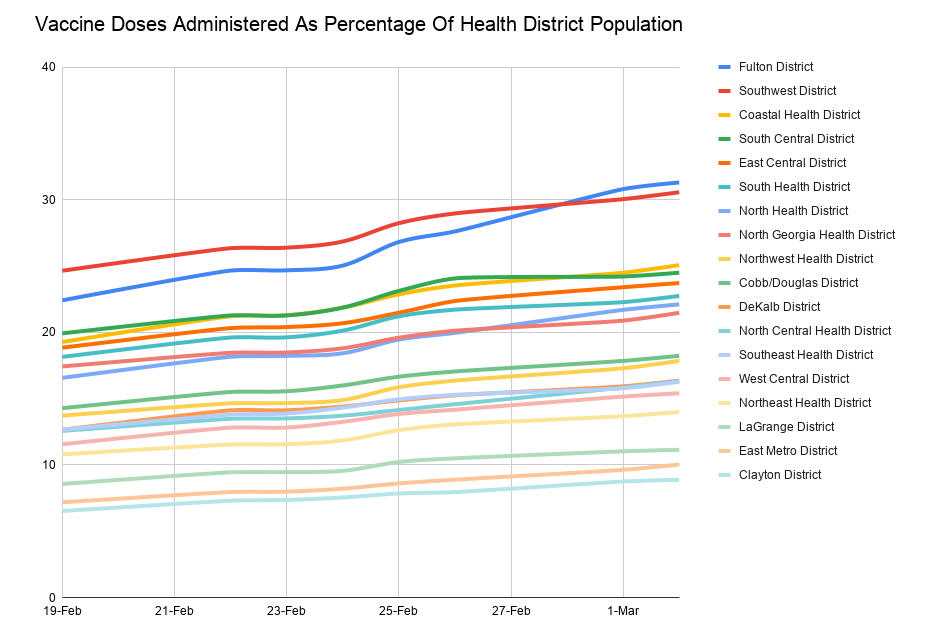

It was only after that shift of materiel that the Fulton Health District overtook the Southwest Health District in the percentage of district's population administered at least one vaccine dose.

The airport site is in Albany City Commission Ward 6, represented by Demetrius Young. He lives close enough to the airport that a conversation in his driveway will be interrupted regularly by a single-engine plane that sounds like it’s just above the roof.

Young began his term on the commission right when the pandemic hit Albany. He said he lost a lot of people last year.

“We were all kind of living with this fear the virus was, you know, going to get you and literally kill you,” he said.

And so you’d think he’d be pushing those living in his ward to get to the airport site and get the vaccine — like public health officials and state leaders have been urging Georgians to do.

But the first-term commissioner takes a completely different tack.

That’s a conversation between you and a doctor, he said. And it’s not his only reason for not advocating for the vaccines.

Albany City Commission member Demetrius Young stands outside his home.

“You have to still think about the motivation,” Young said. “I think, you know, white folks are just ready to get back to normal. And if this gets back to normal, then that’s what they are going to do.”

But Young said “back to normal” would still mean many of his constituents would be really sick. A lot of the COVID comorbidities were epidemic here before COVID-19.

“In this ZIP code, we had the highest rate of diabetes, hypertension,” Young said.

Young said let’s talk about that before we talk about vaccines.

“Until we get ready to have those conversations,” he said, “I don't think you should expect Black folks to just run out and, you know, get in line.

“So it becomes a situation where we can’t allow ourselves to go back to the status quo.”

Something else that’s keeping Black people in Albany from the vaccine is Georgia’s age limit on who can be vaccinated.

So far, the state has largely focused on vaccinating people 65 and over.

That age limit is a wall that many of Dr. Shanti Akers’ patients have been running into. In her Albany practice, Akers sees many of the conditions that are epidemic in Young’s commission ward.

“I have patients in their 20s and 30s with very uncontrolled hypertension to the point that they've already developed renal failure,” Akers said.

Those are patients, again, contending with COVID comorbidities. Akers said these patients tend to be Black, and many want to get vaccinated but haven’t been able to because of the 65-and-older age limit prevents them from signing up.

The number of vaccine doses administered as a percentage of the population of one of Georgia's 18 public health distrticts. Data: Georgia DPH and US Census Bureau

“I mean, it doesn't really help a good number of my patients,” Akers said.

Then there’s the issue of life expectancy.

According to the CDC, life expectancy of white people in Albany ranges from between 75 and 82 years. Meanwhile, Black people in Albany can expect to live between 57 and 75 years.

That means many of the elders in Albany already don’t live long enough to qualify for the COVID-19 vaccine under the existing rules.

Akers says she would like vaccinations prioritized by medical need — instead of age or even race. Or better yet, let’s consider them all.

“I think the best algorithm would be something that sort of gives you a risk stratification based on age, based on race, based on medical problems, and then allows you based on perhaps like a score to determine who is at greatest need,” Akers said.

That’s as long as we have to ration vaccinations, she said.

Dr. Derek Heard says if you can, you need to get in line for the vaccine right now.

Heard was born and raised in Albany and now practices family medicine at Phoebe Putney. He had COVID-19 last November.

Dr. Derek Heard was hospitalized with COVID-19 last year. Now he is a vaccination advocate.

“The first week it felt like a really bad flu, you know, bad fever that wouldn't go away,” he said. “Body aches, just listless, tired. The second week, that's when it got tough. I started getting short of breath.”

Heard ended up in the hospital.

He still gets out of breath climbing stairs. Or when he talks for a long time, which he does a lot these days when he tells his story.

“I tell it every day,” Heard said. “I just told it a few minutes ago.”

It’s the conversation that Demetrius Young in Ward 6 said should happen with doctors instead of him. So Heard tells it to pastors, politicians and, of course, his patients.

And once he does, he asks them to tell the story themselves.

“I say, 'Well, listen, I need you now,’” Heard said. “Go out there, be my microphone. I need you to go out there and tell the people around you that you've had the vaccine, that you're safe, you're not growing horns out of your head. You're not growing a tail out of your back.”

There are also community forums and appearances on local radio stations. But Heard realizes convincing people to get on board with the COVID-19 vaccines will likely be a case of one mind at a time.

Once people are ready, getting the vaccine to them is another problem entirely. Ward 6 Commissioner Young said for many in the ward, transportation is a struggle.

They can’t get to a mass vaccination site, even if it’s just a mile away from them. From their view, it might as well be in another town, Young said.

Those concerns are being heard.

Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital has two RVs kitted out as mobile medical clinics. For now, those will be rolling vaccine sites.

Once the coronavirus is a memory, the mobile clinics will be used to better treat the chronic diseases that made so many in Albany so vulnerable to the worst of COVID-19 in the first place.

It was Peterson’s idea.

“This has been about a three-year dream of mine to mobilize health care,” Peterson said.

It took the pandemic to get the rest of the hospital brass onboard with the operations VP.

“It has been a catapult, unfortunately, that I wouldn't have desired.”