Section Branding

Header Content

An Author Replies To The Unspeakable In Her 'Elegy' For Lynching Victim Mary Turner

Primary Content

A March 7 story about the trial of Derek Chauvin, the police officer whose May 2020 killing of George Floyd ignited a nationwide racial reckoning, shows why Rachel Marie-Crane Williams' new book is so essential right now.

Despite video footage that shocked the world, the Associated Press reports, "legal experts say the case isn't a slam dunk." That's not news. Not after Ahmaud Arbery, Pamela Turner, Stephon Clark, Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Oscar Grant and all the other African-Americans whose killings have been captured on video, a sickening chronicle spanning decades. Some acts, we've learned, trigger an immediate, agonized reaction in anyone who witnesses them — and yet when those acts are described in a courtroom, something crucial always gets lost. Mere words, especially the kinds of words our legal system relies on to deliver verdicts, literally can't do justice to the case.

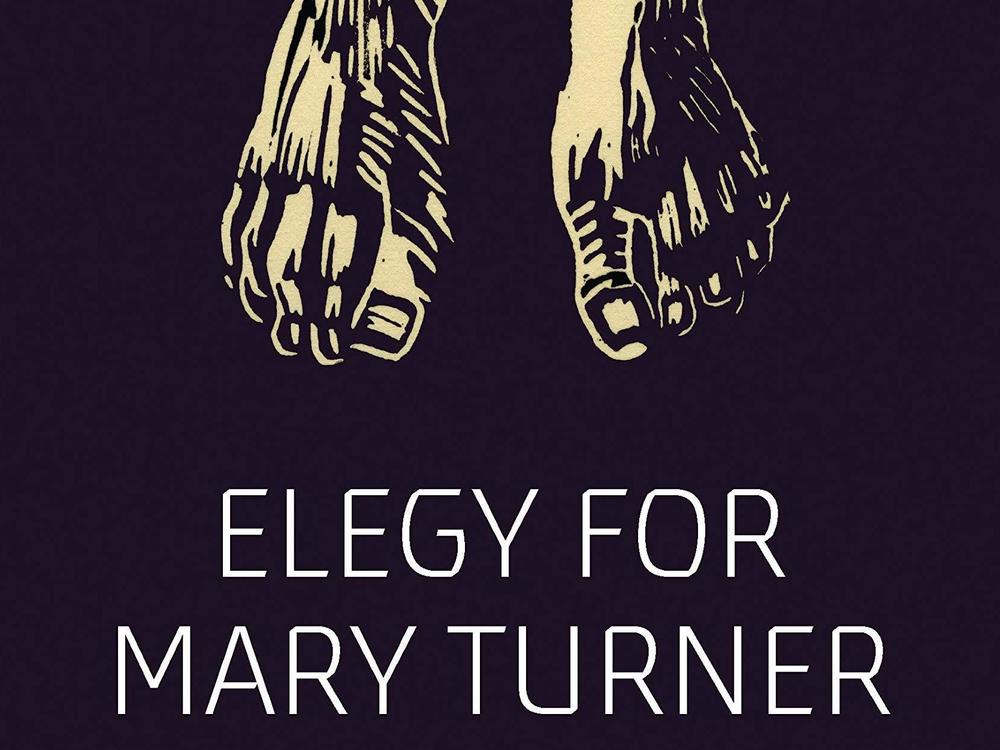

With Elegy for Mary Turner, Williams joins a century-long movement of artists responding to the kind of racist violence that's louder than words. Elegy is a bit of a hybrid of a graphic novel and an art book. Using a mix of original illustrations, archival documents and handwritten text, Williams memorializes 10 black men and one woman, Mary Turner, who were lynched by white residents in Brooks County, Ga., in 1918.

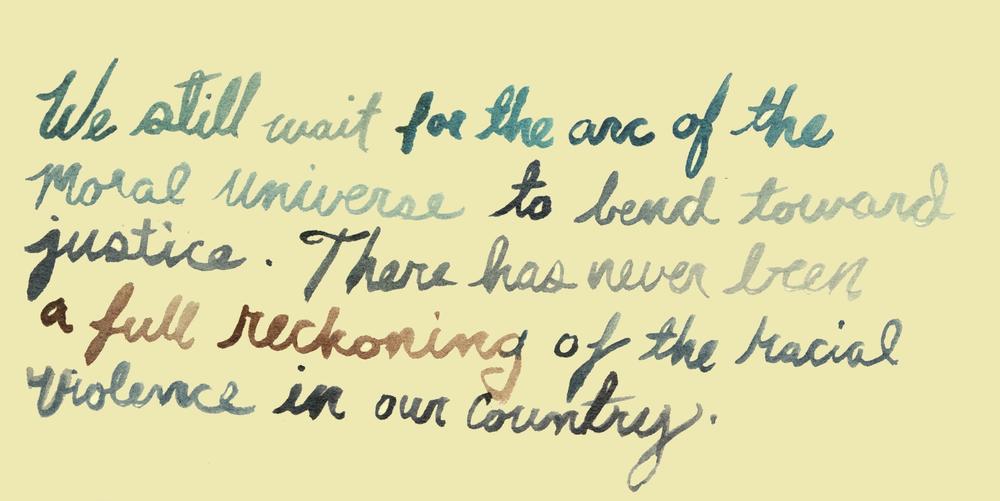

Williams isn't the first artist to turn her attention to Turner's death, or to lynching. The sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller created a work honoring Turner in 1919. Two decades later, Billie Holiday seared the crisis into music history with "Strange Fruit." More recently, the Equal Justice Initiative honored victims with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., which opened in 2018.

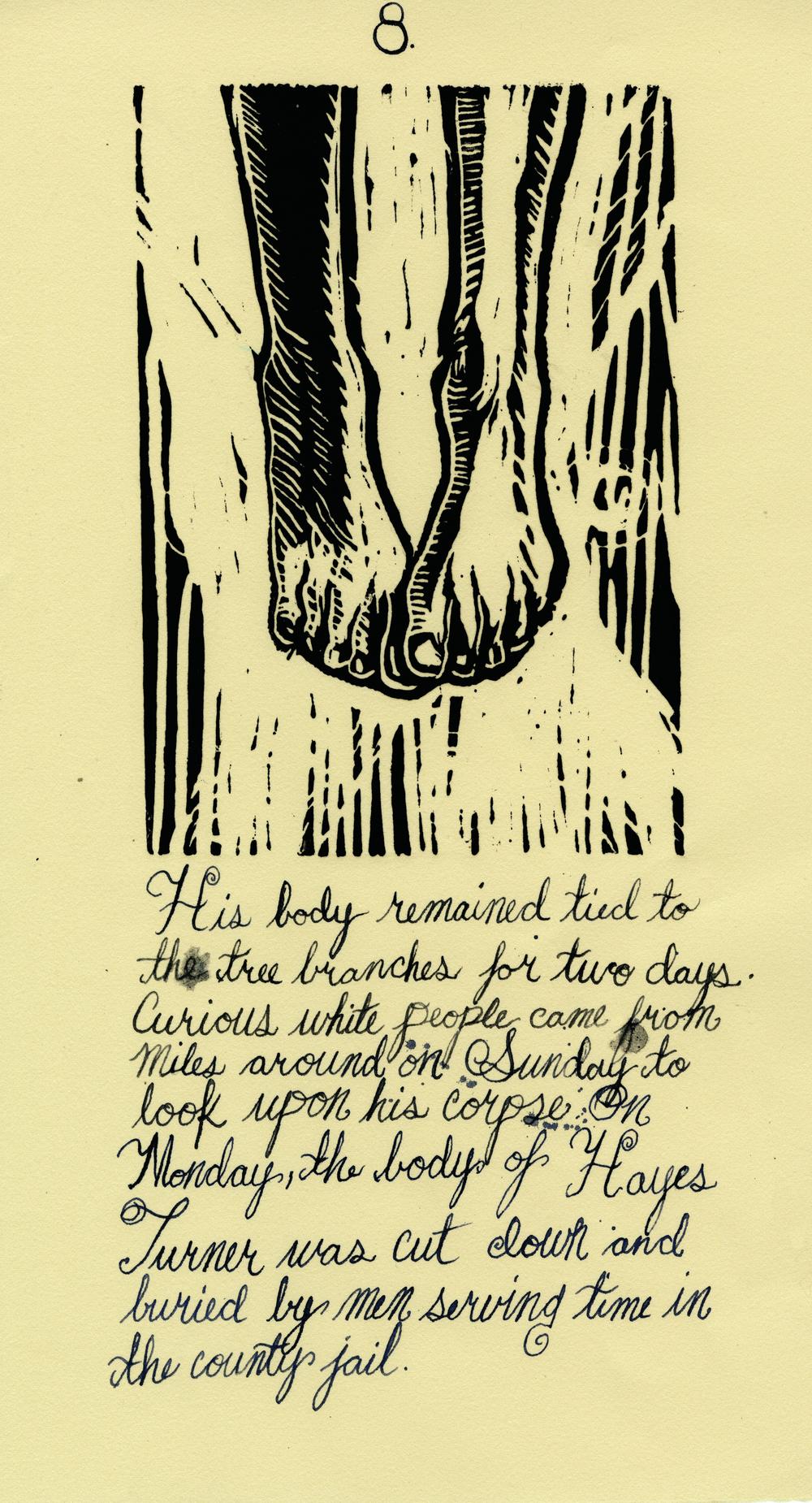

Like the artists whose example she emulates, Williams doesn't just deplore unspeakable evil or try to argue with it. She confronts it in its own realm — the realm of art. Lynching, after all, was no mere retribution. It was ritual. Many lynchings were attended by crowds of hundreds or thousands who'd learned the date and time from the local newspaper. The event was extravagant, theatrical: The astonishingly varied methods the perpetrators dreamed up to desecrate their victims' bodies reflect a grotesque ingenuity. The corpses were often kept on display for days.

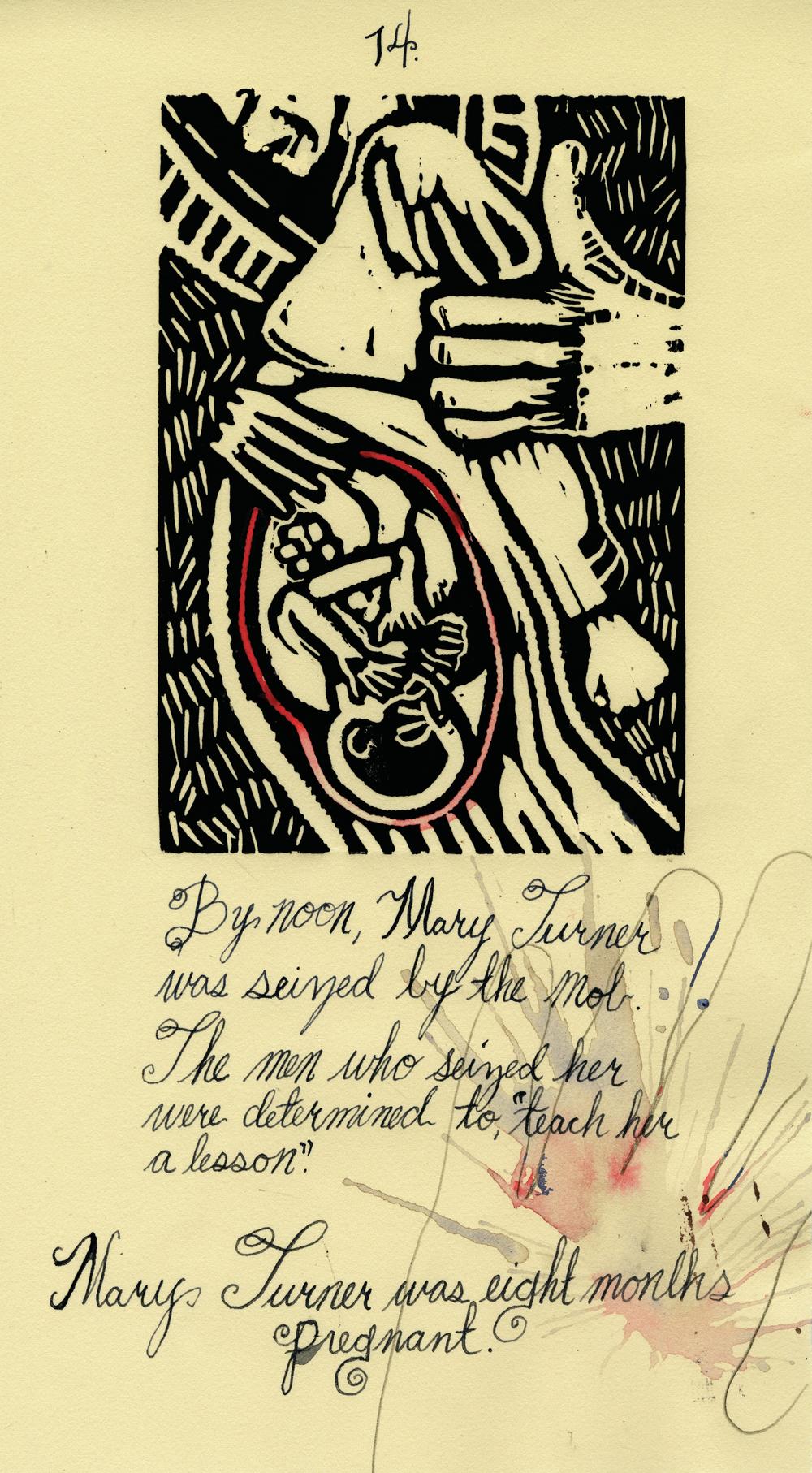

Tersely, Williams describes what happened when the mob seized Mary Turner. (They'd decided to "teach her a lesson" for speaking out against the murder of her husband Hayes, one day earlier, in a wave of violence triggered by the killing of a local plantation owner.) Hanging Turner upside down, they doused her body in gasoline and burned her alive. "When the fire had burned away her clothing, a man took a large butcher knife and slit open her pregnant belly," Williams writes. The 8-month-old fetus fell to the ground, and one man crushed its skull with the heel of his boot.

That's not punishment. It's proof. At a visceral — and thus inarguable — level, lynching showed that racist tyranny was inviolate.

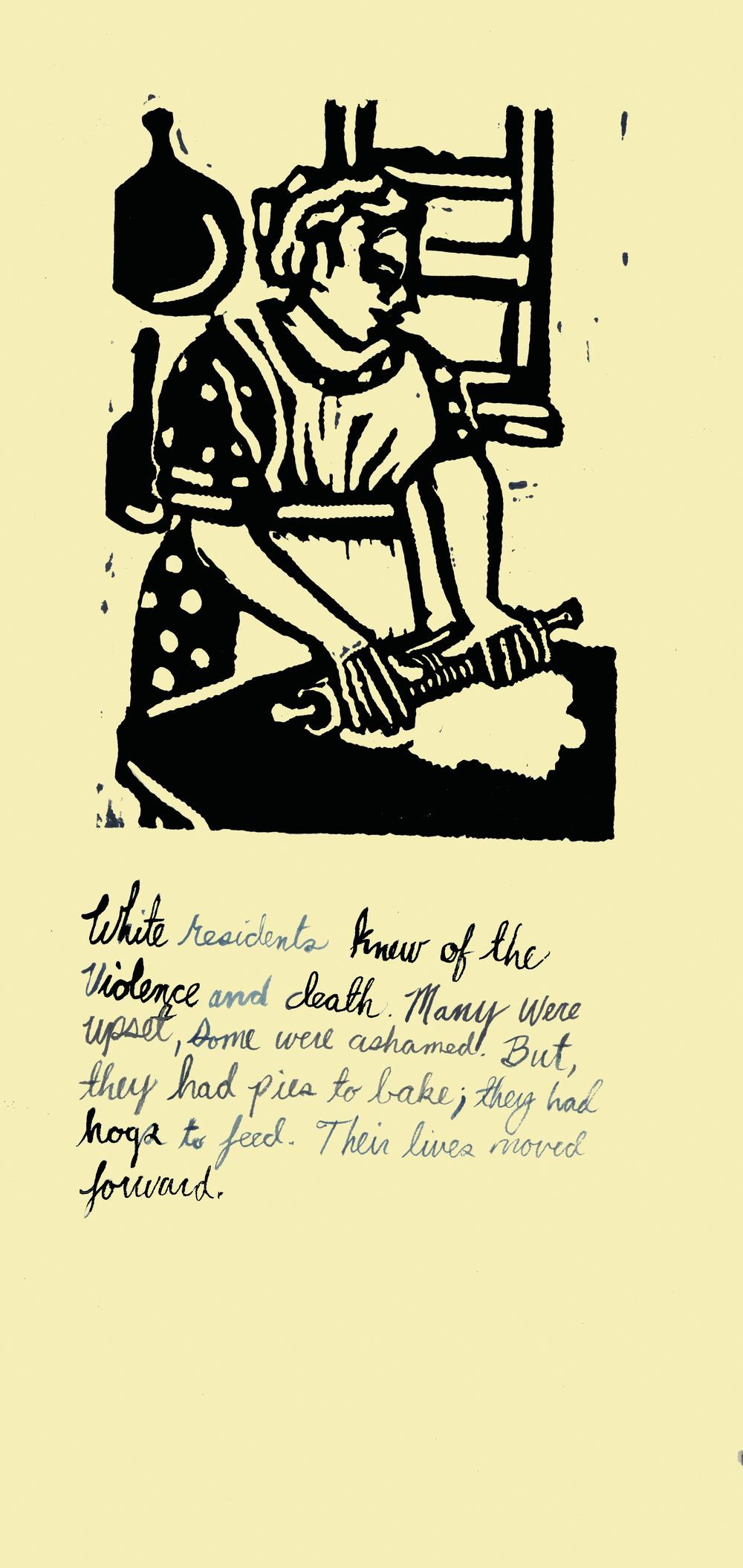

So how do you challenge an evil that transcends language? Williams starts by slowing down. Strikingly, she's chosen to illustrate Turner's story using woodcuts. Unlike sketching with a pen, this method interrupts the flow of emotion with time and technology. You've got to carve a design into a block, wet it with ink (not too much or too little), press it onto paper and watch your image appear in reverse. Williams' brutalist style isn't innovative, but she achieves a variety of effects with it. Some of these illustrations are numbly static; others throb and seethe.

When she does use text, Williams deliberately impedes the reader's eye (and mind). She inscribes two or three sentences per page in awkward, painstaking script. She seems to be deliberately imitating a child's writing style, perhaps to remind the reader of what it felt like to first learn that such things could happen. Her letters are decorative yet irregular, as if she's trying and failing to write in an elegant way. Strange little curlicues pop up here and there. It's a style that's uncannily out of sync with both the chunky illustrations and her factual tone.

She includes a few original documents that "speak" all the louder in the absence of any contextualizing commentary. There's a photo of a wide residential street, idyllic with regularly planted trees and tidy houses, and a page from a farmer's almanac. The latter reveals that Turner was murdered on Pentecost. That's the day on which (as Julie Buckner Armstrong, author of 2011's Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching, points out in an afterword) Christians believe "the Holy Spirit descended on the Apostles in tongues of fire, giving them the power to speak God's message of love in all languages." Mary Turner's killers chose a supremely ironic day for an act that was meant to foreclose the possibility of speech.

Williams' Elegy is a reminder that lynching ultimately failed to do that, and will continue to fail as long as people honor and grieve its victims. Just as importantly, though, Williams demonstrates how to fight the kind of evil that stuns you into silence. If you can't do it with words, go beyond them.

The other side already has — it goes there every day. In a postscript, Turner's great-grandnephew C. Tyrone Forehand tells how Turner's descendants and other activists got a commemorative marker installed in Hahira, Ga., in 2009. "On October 8, 2020, the Mary Turner Project and the Georgia Historical Society had to remove and store the marker due to repeated vandalism," he adds in a footnote. "In its place a large steel cross was erected to temporarily mark the site of Mary Turner's murder."

Etelka Lehoczky has written about books for The Atlantic, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The New York Times. She tweets at @EtelkaL.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content