Section Branding

Header Content

Plywood From Boarded-Up Shops Turned Into Art Commemorating Floyd Killing

Primary Content

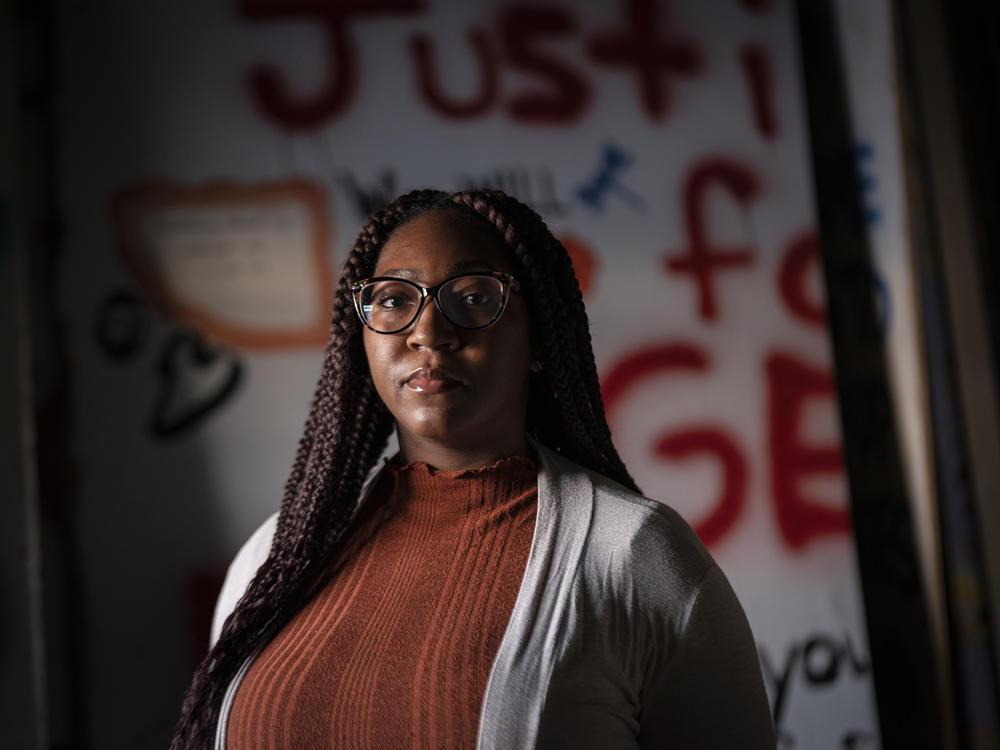

Leesa Kelly unlocks the orange metal gates and then the double doors of a storage unit on the far end of an industrial building in the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District.

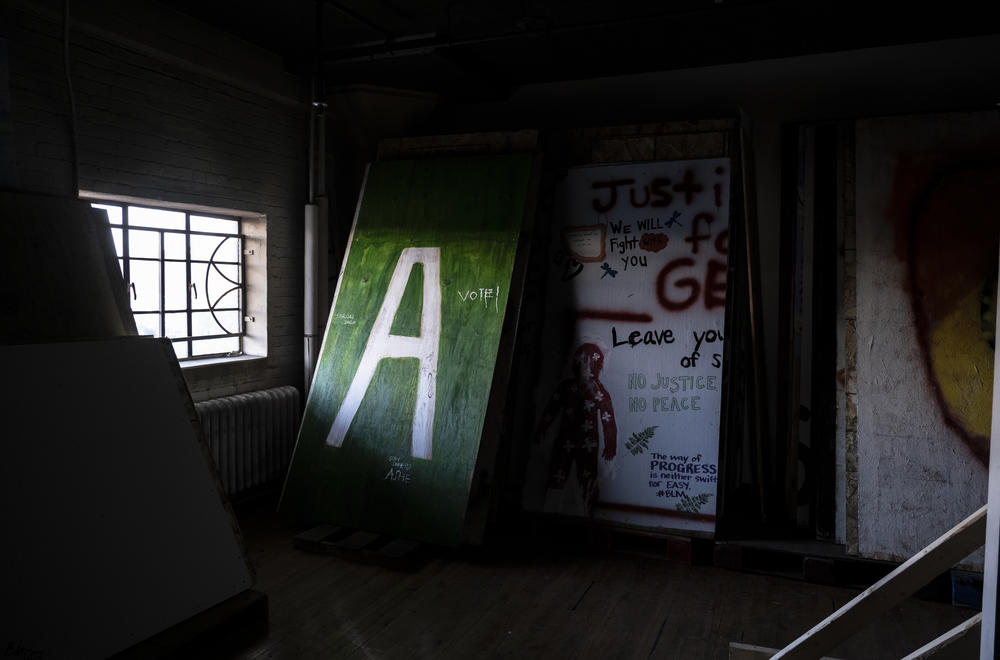

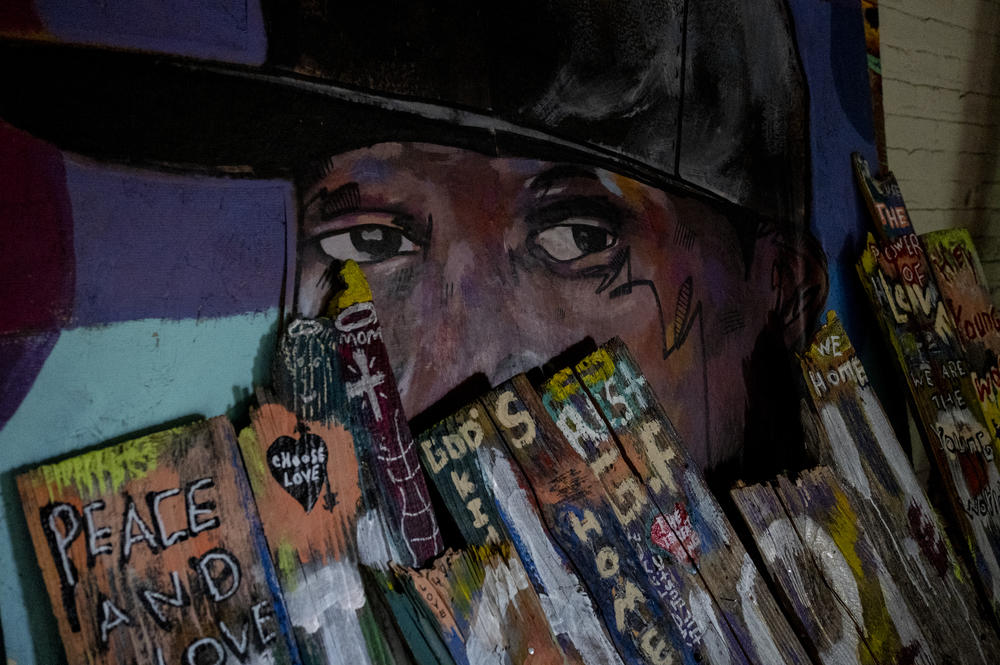

Inside are hundreds of painted plywood boards. There are portraits of Floyd's unsmiling face, others of fists raised in the air. One board is pink with the words, "Black Girl Magic," and another with the plea, "Please Don't Hurt Us."

These are the boards that business owners put up in the midst of mass protests last year after the killing of George Floyd. The video of Floyd losing his life while his neck was pinned to the ground by a police officer's knee sparked protests across this city. Buildings burned, police used less lethal bullets and tear gas on demonstrators. The city was in pain.

"There were a lot of complex emotions at play within people's bodies," Kelly said. "All of a sudden, out of nowhere, there's this blank canvas all around the city and no one kind of had ownership of it. No one knew what to do with it. And so people just started painting."

Boards that were put up to protect buildings from civil unrest became vehicles of expression for devastated and angry Minnesotans — a mural of this summer in art and words.

"If you look around this room, it tells you a really full and complete story of what happened to George Floyd and what happened to our city in the months following his death," Kelly said. "Fifty years from now, when people are wondering what happened with the Minneapolis uprisings of 2020, they can literally come back to these boards and learn the entire history just from what's painted here."

Before George Floyd was killed Kelly was a lifestyle and travel blogger. But his recorded death set her on a journey to find something she could do to help her community. That search led her to these boards.

Where would this recorded history on these temporarily erected planks go? she wondered. So she founded Memorialize the Movement. After a local news article about her work also featured Kenda Zellner-Smith and the similar work she did with her organization, Save the Boards, the pair teamed up in August to collect and preserve these murals that appeared across the Twin Cities in the days and weeks after Floyd's killing. The goal is to share them as a constant reminder of what happened in the summer of 2020.

Right now they're photographing each board and creating a digital archive in partnership with the St. Paul-based University of St. Thomas. Students and researchers from the university are helping collect every bit of information they can on each board: where they hung, when and who painted them. When the archive is done it'll be shared online. Kelly said she's looking for a space for the boards to hang permanently.

In the meantime, an exhibition is planned in collaboration with the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum & Gallery. For three days in May some 200 boards will be on display in Phelps Field Park, a five-minute walk from the site where Floyd was killed.

Now Kelly visits this warehouse every week. On a recent day she walked through the two rooms where piles of boards leaned up against every inch of wall space. They were organized by what part of the city they came from.

She pointed to one pile that once covered windows of a local CVS, about 40 boards in all.

"We decided to give them a stack of their own," she said. "It's one of the only sets of boards that we collected where we were able to identify that the artists were Black women."

It's not easy reading the messages in these rooms, she said. A poem Kelly finds particularly powerful peeks out from the back of one stack:

"NOT THE FIRST MURDER NOR THE LAST

STORMS THAT NEVER SEEM TO PASS..."

"A lot of times I try not to spend a lot of time reading these because I just kind of get emotional and it all comes back and there's a lot of trauma associated with it all," she said.

But she doesn't turn away, because she can't.

"This country is not a safe place for Black and brown people," she said. "It's not a place where we feel good walking down the street by ourselves, or driving in our car, or wearing a hoodie, or eating an ice cream, or holding a cell phone."

She also draws strength from the collection. Her favorite pieces come from the site where George Floyd was killed. These ones are canvas.

"Thousands of messages in dozens of languages from people not just in Minneapolis, not just in the country, but all over the world who came to the square to visit and to pay their respects," she said. "What really moves me about it is that I'm not alone in this. Black people are not alone in this."

Jury selection is underway in the murder trial against the white former police officer Derek Chauvin accused of killing Floyd. It's opening up these wounds again. Wounds, she said, that cannot heal until there is change. On the first day of pretrial motions last week she took three of these boards to a demonstration outside the government complex where the courtroom is housed. Among them, a black-and-white portrait of Floyd's face.

She felt strongly that local officials, the police, even Chauvin, should be confronted with a portrait of Floyd at the start of the trial.

"He may be gone, but we're still here and we're still hurting," Kelly said.

She's hoping the verdict is a conviction and a lengthy prison sentence. That, she said, will tell the world that there are consequences when police take a Black life. But it's rare that police are convicted in cases like these, and she's also afraid that may be the outcome here.

"It will be really bad if he's not convicted because so many people need this. So many people want to see this change. They want to see that precedent set," she said. "On the opposite end of that, so many people want to see him walk free. And right now, everyone's just feeling so strongly about their side. And so I'm scared. I don't know what will happen."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.