Section Branding

Header Content

The Music Of 'Justice League' Is Its Own Epic Tale Of Death And Rebirth

Primary Content

In some ways, making a movie isn't too different from running a business: At the end of the day, it's just a set of relationships. Financial interests clash with creative ones. The mission depends on who's in charge. And when new management comes in, sometimes people further down the chain find themselves suddenly out of a job, too.

In 2017, when director Zack Snyder left the DC Universe film Justice League in the middle of production, Tom Holkenborg was among the collateral damage. The Dutch composer, better known by his electronica stage name Junkie XL, had worked on two other Snyder superhero blockbusters, as well as genre smashes like Deadpool and Mad Max: Fury Road. But his resume wasn't enough to save him from a chaotic shuffle that included a new director, extensive reshoots and film music giant Danny Elfman, recruited at short notice to take over the music with help from Captain Marvel composer Pinar Toprak.

Holkenborg, now 53, is far from the first film composer to lose his spot at the eleventh hour. But he might be the first to ever get his job back. Four years after he was canned, Holkenborg's name is back in the main credits of Zack Snyder's Justice League, the four-hour epic premiering today on HBO Max. And his equally long score — a colossal mashup of operatic orchestra, rock, synthesizers and wailing vocals — is, for some, as hotly anticipated as the expanded exploits of Ben Affleck's Batman and company.

Justice League was envisioned as the third chapter in a Snyder-helmed trilogy based on DC Comics' brightest stars, which began in 2013 with Man of Steel and the introduction of Henry Cavill as an angsty new Superman. Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) added Affleck's grumpy Dark Knight and Gal Gadot's idealistic Wonder Woman, and Justice League promised an expanding universe, with the established characters recruiting other DC titans to fight an otherworldly evil too great for any of them to face alone.

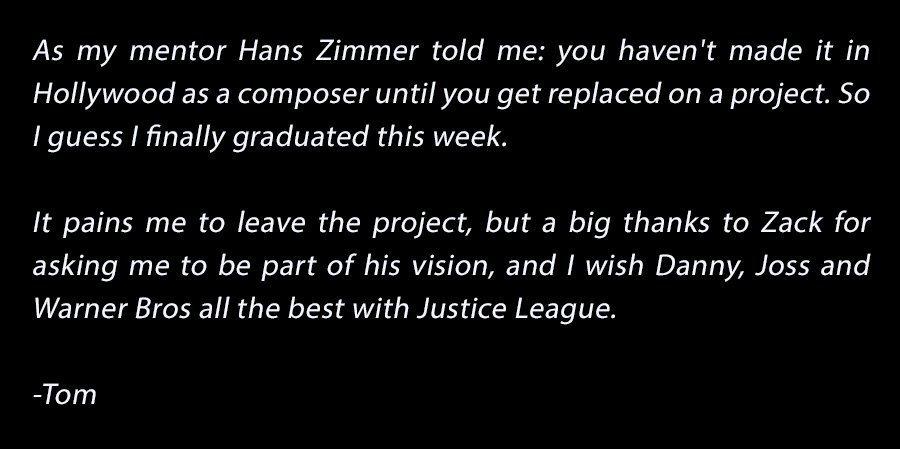

When Holkenborg got the axe, his mentor and Batman v Superman co-composer Hans Zimmer told him, "You haven't made it in Hollywood as a composer until you get replaced on a project." (I recently asked Zimmer what advice he gave his friend when it happened. His answer was succinct: "Drink heavily!") Though it doesn't make the same kind of stir as recasting a lead role, dozens if not hundreds of major films have had their scores tossed out over the years.

Among the most prominent are Alex North's score for 2001: A Space Odyssey, which director Stanley Kubrick dropped in favor of his famous classical mixtape; Bernard Herrmann's aborted final collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock on Torn Curtain; David Shire's electronic score for Apocalypse Now; Phillip Lambro's Chinatown, which Jerry Goldsmith iconically replaced in just 10 days; Goldsmith's own rejected scores for Legend, Babe, Wall Street and a host of other movies; and Randy Newman's jettisoned action score for Air Force One. Pulling a score can be disruptive and, depending when it happens, expensive, given the considerable cost of recording an orchestra. But with the possible exception of John Williams, it seems to happen at least once in every film composer's career.

"You can usually see it coming," says Marco Beltrami, whose distinctions include scoring Logan and World War Z and being fired from the 2007 animated feature TMNT. In Beltrami's experience, it generally isn't a direct rift between director and composer that leads to a score being dropped, but rather circumstances where "other people that are involved that have sway over the director, and they have a different idea about what should happen. Then it can become very difficult. It's almost like you get soured in their eyes, and anything you do is wrong."

In the case of Justice League, it was a confluence of calamities, most definitively recounted in a recent Vanity Fair piece. After Warner Bros.' disappointment with Batman v Superman, Snyder was under pressure to lighten the tone and keep his team-up movie under two hours. Then, during production, came a tragedy: His 20-year-old daughter, Autumn, took her own life. With the fight knocked out of him, Snyder left the project to be with his family.

Holkenborg was heartbroken for his collaborator, whom he first met while working on Man of Steel with Zimmer. It was like "seeing your friend in 10,000 pieces," says the composer. "And at the same time, you know, 'the show must go on, and we must finish this movie.' It was horrible, you know? You don't want a creative process to be like that."

The studio turned to the wisecracking Joss Whedon, known for his work on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Marvel's own super-team franchise, The Avengers. Though credited with merely finishing Snyder's cut, Whedon actually rewrote and reshot as much as 75 percent of the film that was released in theaters on Nov. 17, 2017.

Holkenborg says he had just one meeting with the director. "We did not necessarily have a great click," he says. "I mean, I wasn't sitting there being thrilled to talk to him, because he was quite negative on the cut that was existing and what we worked on together. He was negative about the music that was in there at that point. He was negative about a lot of things in it. And I was like, 'Hey, you're talking about my friend here.' So I wasn't really inclined to take that further. I spoke to Zack that night and said, 'I'm leaning towards not doing it.' But then the next morning, I got a phone call that [Whedon] was going to work with Danny Elfman."

(In recent months, a chorus of others — particularly Ray Fisher, who plays Cyborg in Justice League, and Buffy's Charisma Carpenter — have voiced their own less-than-thrilling experiences working with Joss Whedon, though Holkenborg didn't characterize his own experience as abusive. A representative for Whedon declined to comment on the meeting for this story.)

A campaign to resurrect Holkenborg's score began almost immediately, one of the headline requests of a Change.org petition by a loud legion of fans asking Warner Bros. to #ReleaseTheSnyderCut. The movement gained steam when Snyder confirmed he had preserved his four-hour rough cut of the film, and some of its stars joined the effort to get it out into the world. At the end of 2019, the composer learned that WarnerMedia, which owns HBO Max, was seriously considering investing in Snyder's grand concept. Last May, he got the call: Snyder had a green light, and wanted his maestro back.

If the word "visionary" has been central to Zack Snyder's branding since he first broke through in the 2000s, this Homeric new cut is the ultimate auteurist, blank-check realization of that vision. It features restored sequences that were trimmed or flushed by Whedon, new scenes featuring Batman and Jared Leto's Joker, a deep backstory for Cyborg and shiny new VFX — all in an arty 4:3 aspect ratio and a much darker palette, visually and tonally, than Whedon's edition.

When Holkenborg revisited the music he'd written in 2016 and '17, he realized he'd only scored about 50 percent of that version of the movie, which was only going to be two hours long to begin with. Besides feeling that he'd evolved dramatically as a composer in the intervening years, he also says that when he heard his old score, "I noticed immediately that I came back into that tunnel vision or vortex of negative energy that I felt when we had to quit. And that I didn't want."

So he decided to start over.

That meant six months to write and record four hours of original music, during a global pandemic. Set up in a spare, eight-by-eight-foot room in his house with a computer, a few synths, a drum kit and some guitars, and with no assistants, Holkenborg commenced work on this $70 million redo of a $300 million blockbuster, using the same tools a bedroom pop artist like Billie Eilish might. But there was a major upside to this scaled-down approach: He had only one person to please.

"There was now no team effort of a studio, producers, other people that have something to say about the end product," Holkenborg says. "I had a director that was egging me on twice a week: 'Make sure it's extreme as you want to take it, you know — wherever you feel it's appropriate.' [The timeline] turned it into such an intense experience, and the music became so much more intense than the original ever was."

Like Snyder, back in 2016 Holkenborg was pressured to lighten the tone of his approach. Now, he could lay into as much dark and dense bombast and as many wild, genre-hopping ideas as he pleased. If he wanted to punctuate a funny line by Bruce Wayne with "a really slamming trap beat with a weird synth on top," he could. When Batman jumps out of a ship to kick some alien ass, "instead of starting with sinister orchestral tones, I was like, 'No, no, no, we should do a really cool stoner riff here, with a fuzz box and my old Jimi Hendrix Marshall amp in the back of the room.' And Zack was like, 'Oh, I want to hear that!'" He took a kitchen sink approach, pumping his past lives as an electronic artist, remixer, producer of heavy metal bands, drummer and Hollywood composer into the most ambitious project of his career.

Strings and brass were recorded remotely at AIR Studios in London, under strict COVID safety protocols. Besides further developing Zimmer's memorable piano theme from Man of Steel and the electric cello riff they wrote together for Wonder Woman in Batman v Superman, Holkenborg came up with a new Wonder Woman idea for Iranian singer Delaram Kamareh, a new tragic theme for Cyborg, and a unifying melody for the Justice League itself.

A month ago, he got his first taste of feedback when the track "The Crew at Warpower" was released as an early single. "In less than 24 hours it was like 250,000 people streaming that thing, and just leaving incredibly warm comments. ... That did not happen before in my career," he says. "It was like running a marathon with the best f******crowds along the way the whole time. Everywhere there are people that are cheering for you, and yelling for you."

Rabid movie fans, of course, often yell at people — and there's a fine line between the campaigning Snyder's fans did on behalf of a cherished product and the bullying they and their cultural cousins, devoted to Star Wars and other mega-franchises, do when their wrath is provoked. But at least in Holkenborg's case, the fandom was a source of constant encouragement.

"There were days I woke up in the morning, I didn't know how I was going to finish it," he says. "But only one peek at your social media, with a few hundred more comments filled by DC fans around the world that are so happy that this thing is finally being made — that was the marathon crowd that kept me going."

The success of the movement to release Zack Snyder's Justice League may well lead to other fan-mandated restorations and after-the-fact alterations, but as far as film music it's likely to remain an anomaly. Once in a great while, a shelved score might gather enough cult fascination to be released years later as a standalone album or a Blu-ray bonus feature. But most of the time, once a composer gets fired from a movie, all they can hope for is to find their work another home. That's why Marco Beltrami — who turned a melody from a rejected score he wrote for the 2001 Western Texas Rangers into his main theme for Hellboy — says he has a folder of 100 more unused score pieces on deck. As he puts it, "I am all about recycling."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.