Section Branding

Header Content

'Perseverance' And Poetry Help A Writer Bridge Multiple Worlds

Primary Content

For people who are deaf the world is often split in two: A world where sound is taken for granted, and another with its own rich culture of deaf history and sign language.

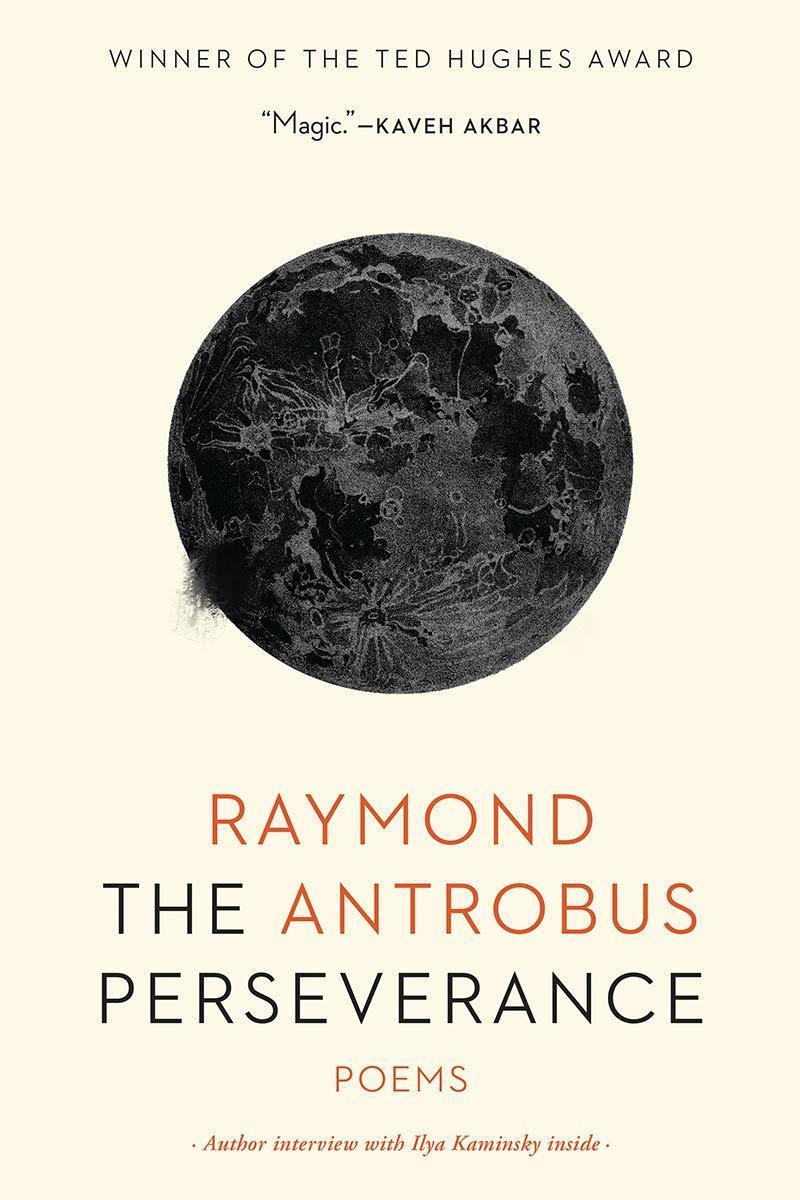

Poet Raymond Antrobus has always had to navigate between these two worlds, something he examines in his debut collection The Perseverance, out in the United States just in time for National Poetry Month.

Antrobus was born in East London to a Jamaican father and British mother. And he was deaf, but no one realized it for the first seven years of his life.

At first, his parents assumed he had learning difficulties — perhaps dyslexia — until one day Antrobus' mother bought a new telephone for the house. It was loud, and his parents noticed that he was the only person that never responded to it, even when he was in the same room.

"So it was the telephone that kind of diagnosed my deafness," Antrobus says.

At 11, he enrolled in a deaf school, where he started learning sign language. And after graduation he went straight into the workforce. "I had a lot of jobs," he says. "But I was losing a lot of my jobs because I left school pretending I was a hearing person."

Antrobus realized that passing as a hearing person wasn't helping him, so he decided to turn to poetry for solace. It was a medium he'd been dabbling in since he was in school. "My grandfather was a poet, a preacher, and I think that was part of grounding me," he says. "For me, poetry always had a place where I could go to listen or to be heard or to belong."

Antrobus also remembers a teacher in school who always encouraged him to write and knew he used to carry around what she called "the big red book."

"She'd be like, 'Raymond, where's your big red book?' and she never corrected [the poems]," he says. "So it always had this kind of space where I could just be."

And when his father died five years ago, his relationship to poetry became stronger. He started seeing a therapist who helped him think about his childhood while writing most of the poems in his debut.

In fact, the title of his book, The Perseverance, is actually the name of a pub where his father used to hang out.

"I have quite a few poems about seeing my dad in the pub and as a kid, realizing how many memories I had of being left outside the pub," Antrobus says. "And the version of my dad that went into the pub was different from the version of my dad that came out."

The poet has since grappled with the idea that maybe some of his mental health issues were rooted in the fact that he never really knew what version of his dad to anticipate.

His relationship with his father shows up in many poems. Here's an excerpt from one:

My Dad never called me deaf,

even when he saw the audiogram.

He'd say, you're limited,

so you can turn the TV up.

Antrobus explains that this was because his father's understanding of deafness was rooted in a different time, a different place. "I would go to Jamaica as a kid with him. And I remember him saying to me, 'You know, you're lucky you're not in Jamaica," he says.

He explores that idea further, later in that same poem:

He didn't mean to be cruel.

He was thinking about his friend

at school in Jamaica who stabbed

Another boy's eardrums with pencils.

Dad never saw him in class again.

Maybe that's what he was afraid of;

that the deaf disappear, get carried away

bleeding from their ears.

As a kid, Antrobus says he was glad that he lived in London, where he had access to hearing aids and deaf schools. But since writing the book, he has returned to Jamaica and worked with deaf Jamaicans.

"I've learned a little bit of Jamaican sign language and I've seen the kind of deaf schools that they've got in Jamaica," he says. "And there are some really great ones." Growing up, Antrobus recalls, he wasn't taught much about deaf culture or the richness of sign language — on top of his late diagnosis — so learning about deaf life in Jamaica helped ease some of his fears.

He explores this upbringing in his poem "Dear Hearing World." Here is an excerpt:

... I was pronouncing what I heard

but your judgment made all my syllables disappear,

your magic master trick hearing world — drowning out the quiet,

bursting all speech bubbles in my graphic childhood,

you are glad to benefit from audio supremacy ...

Fellow deaf poet Ilya Kaminsky, who didn't get hearing aids till he moved to the United States from the USSR at 16, relates to this experience of deafness being ostracized. And he appreciates how Antrobus considers language.

"He's meditating both in English with all the colonial history of English language," Kaminsky says, "and also on sign language, which is very much part of its own unique and distinct culture and history."

Kaminsky is also personally moved by the way Antrobus' poems speak to the senses. "The poems are alive on the page, but also in the palms. The poems are alive on the hands, but also in the ears."

It's this duality that Antrobus now celebrates. When he recently returned to his old school, he saw his old teacher from back in the day — the one who knew about his "big red book". And she said to him, "So, have you accepted that you're a deaf person yet?"

He has. And it was poetry that helped him do it.

"It was never really a thing where I sat down and thought, oh I'm a deaf poet I'm going to write about how I experience sound," he says. "Poetry was a way for me to just write what my truth was. I think there was a kind of listening I had to do to myself and my own history and to give back to the page."

This story was edited for radio by Reena Advani and adapted for the Web by Jeevika Verma and Petra Mayer.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.