Section Branding

Header Content

Chinese Ship Deployment Roils South China Sea

Primary Content

China has provoked international alarm by massing ships in the South China Sea near a reef claimed by both China and the Philippines. This week, Manila formally protested what it called a violation of "its sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction." The United States and Western allies backed the Philippine call for China to immediately withdraw what appears to be a flotilla of fishing vessels.

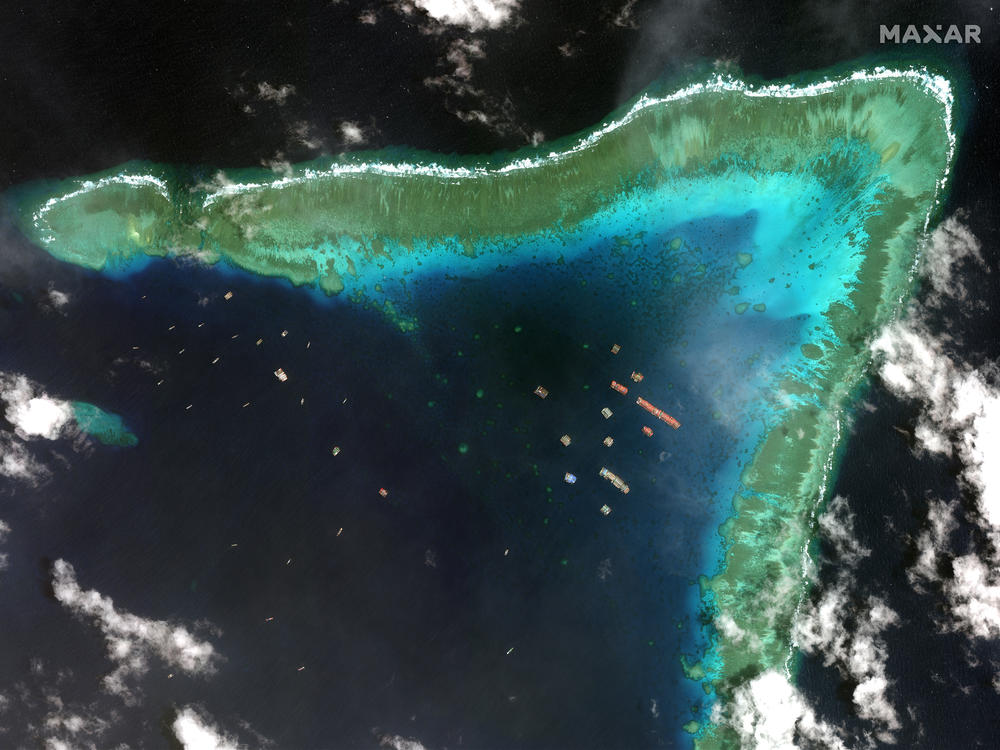

Satellite imagery obtained by NPR from Maxar Technologies shows Chinese vessels moored in the crook of the boomerang-shaped coral bar known as Whitsun Reef — also called Julian Filipe Reef in the Philippines and Niu'e Jiao in China. It lies 175 nautical miles west of the western Philippine province of Palawan, well within the country's 200-mile exclusive economic zone.

The images show Chinese boats, some lashed 10 abreast together, lingering in the waters of the reef that lies just beneath the surface. The Philippine coast guard reported spotting 220 vessels on March 7.

China claims much of the South China Sea for itself and has built several artificial islands, as have some of the other claimants to the contested waters. But the scale of China's building far exceeds that of other countries, and this latest move has drawn international concern. It's raised fears that China perhaps aims to occupy and reclaim Whitsun Reef while intimidating its regional rivals.

"On Monday, a reconnaissance flight by the Philippine Air Force showed that 183 of them were still there. So, you basically have around 200 vessels that have been there for weeks now," says Jay Batongbacal, director of the University of the Philippines Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea.

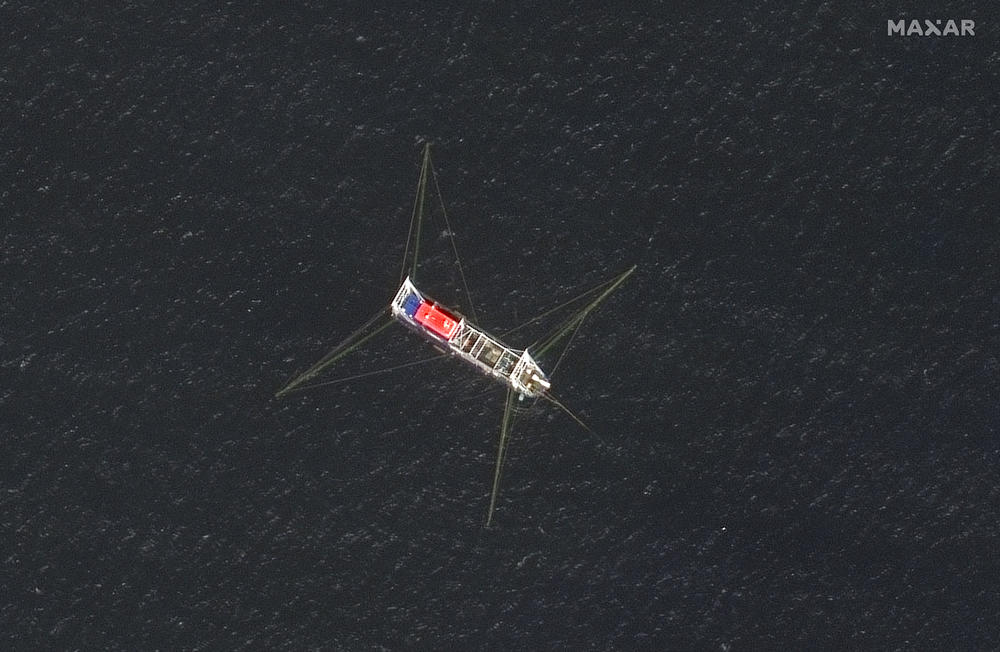

"Satellite photos also show that the decks of these vessels are very, very clean. It's as if they're brand new," Batongbacal says.

Gregory Poling says that's suspicious. Poling runs the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. He says the boats, tied up "with military precision" beside each other, "are not fishing," they're parked.

"You can't trawl while sitting still. So, if these were commercial fishermen, they'd all be bankrupt," Poling says.

The reef where the Chinese ships are massed lies on the northern edge of a larger atoll known as Union Banks, inside the sprawling Spratly Islands chain, known for its disputed ownership. Historically Union Banks has been a fishing ground for Filipino fishermen.

Poling says Whitsun Reef lies within a mile of two of existing Chinese bases and four small Vietnamese outposts. "So, it's a pretty congested area," he says. "And for China, it seems like they are now using Whitsun Reef as an anchorage, a safe place to harbor around this bigger area called Union Banks."

The Chinese have denied they are up to anything unusual and said that its "fishing vessels" were merely sheltering from "rough seas."

Batongbacal says there have been no "adverse weather conditions" in the area in the weeks the Chinese have been there.

What's China doing?

"One big worry, of course, is that they might be preparing to occupy the reef ... in order to construct another artificial island," says Batongbacal, adding, "We've seen it happen before."

He says the episode bears the earmarks of China's takeover of Mischief Reef in the 1990s. Today the reef is China's biggest outpost in the South China Sea. Mischief sits on the eastern edge of the seven artificial islands China has built in the Spratly archipelago.

Batongbacal says back then, China said that it was using the reef to shelter fishermen. By 2015, he says the Chinese had built one of the world's largest artificial islands, which "now hosts a full-blown military base," all protected by "missile emplacements."

Controlling the waters?

Whitsun is unlikely to become another artificial island, believes Poling. "China's goal is to control the water, the seabed, the airspace. And so they don't really need an eighth outpost to do that. What they need is an overwhelming dominance when it comes to the number of vessels in the Spratlys," he says.

Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan also claim parts of the South China Sea. China's claims to nearly all of the waters were rejected by a ruling in a tribunal at the Hague in 2016.

Poling says to assert its vast claim, Beijing increasingly uses its fishing fleet as a maritime militia.

"They're a force multiplier for the China Coast Guard and the Chinese Navy," says Poling, aiding with surveillance, or supplies, or to keep away rival claimants. "But most dangerously, they are used as a coercive element. So you put a whole bunch of them in an area where you want to bully one of the neighbors without actually shooting anybody."

A statement released Monday by Beijing's Embassy in Manila said, "There is no Chinese Maritime Militia as alleged. Any speculation in such helps nothing but causes unnecessary irritation."

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has gone out of his way to not irritate Beijing, and Batongbacal says Duterte has been "very, very accommodating" to China in the South China Sea. "The Chinese are emboldened."

Indeed, Poling says China's maritime intimidation is discouraging oil and gas exploration, and jeopardizing fishermen. It's getting "harder and harder," he says, not to see this an "implicit threat" that carries the added risk of miscalculation.

This week, Philippine National Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana called the Chinese move a "clear provocative action" of "grave" concern. "We call on the Chinese to stop this incursion and immediately recall these boats violating our maritime rights and encroaching into our sovereign territory," his statement read.

Poling says the Chinese are not likely to disperse. "Once China moves in, it doesn't leave. It might decrease the number. It might play nice for a little while, maybe it ratchets down the tension for short term political gain, but it is unlikely to vacate this reef," he says.

The U.S. embassy in the Philippines chimed in: "The PRC uses maritime militia to intimidate, provoke, and threaten other nations," adding, "We stand with the Philippines, our oldest treaty ally in Asia."

Japan, Australia, the U.K. and Canada lent support, saying the Chinese flotilla was threatening regional security.

Poling says the unified call for China to withdraw shows "a realignment of international fears and anxieties about Beijing's maritime claims."

He says that if the international community is going to draw a line in the sand, or try to "compel or cajole" China into compromise, "it has to do so now." The "space for compromise," Poling says, "is getting worrying small."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.