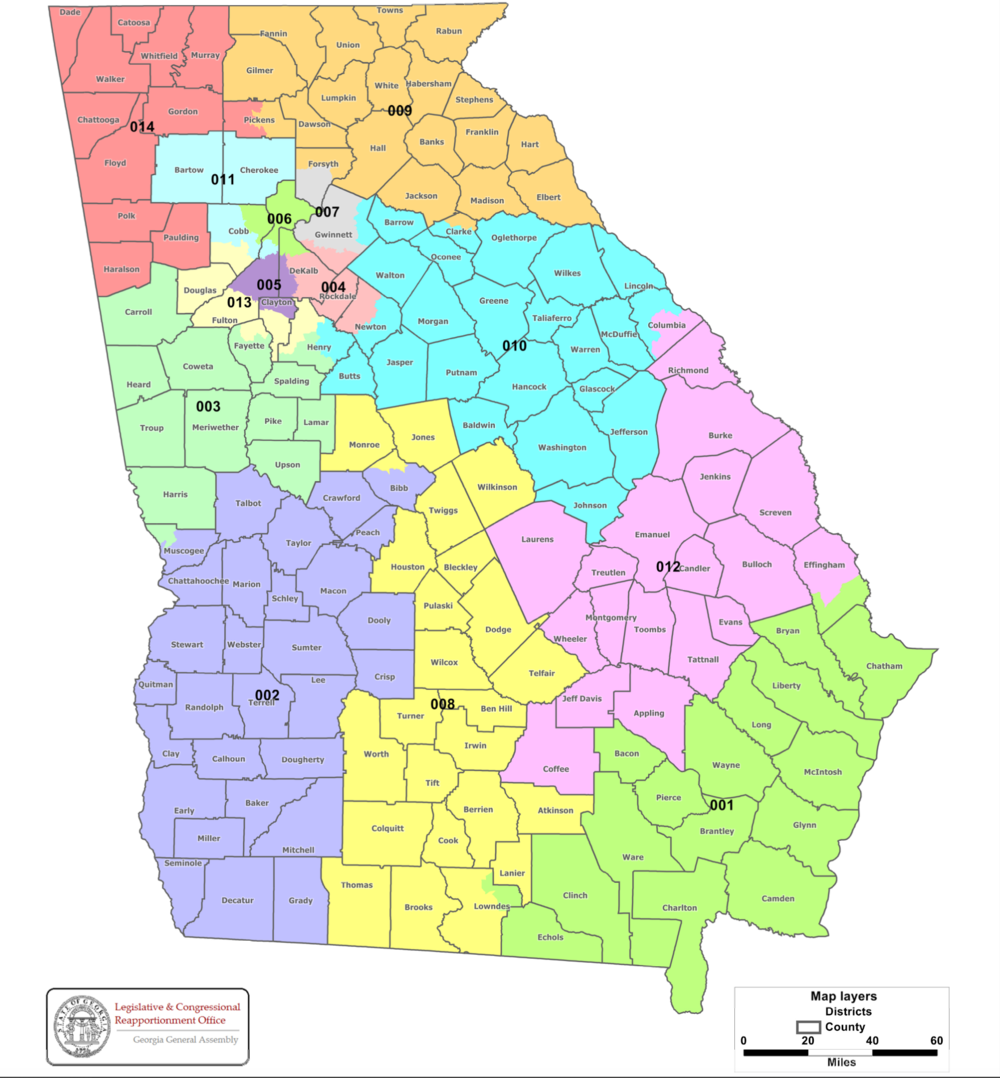

Caption

The Georgia Congressional District map, here in its 2020 configuration, could look considerably different when the Georgia General Assembly — currently controlled by Republicans — conducts its once-per-decade redrawing of the map in 2021.

Credit: Georgia General Assembly