Section Branding

Header Content

Long-Delayed Medicaid Report Outlines State's Ambitious Strategies

Primary Content

Georgia’s new report on Medicaid quality, which came out more than a year late, says state officials will focus more on addressing health disparities in the public insurance program.

The report, released April 1, is a road map outlining the goals of the Georgia Medicaid program for the next two years.

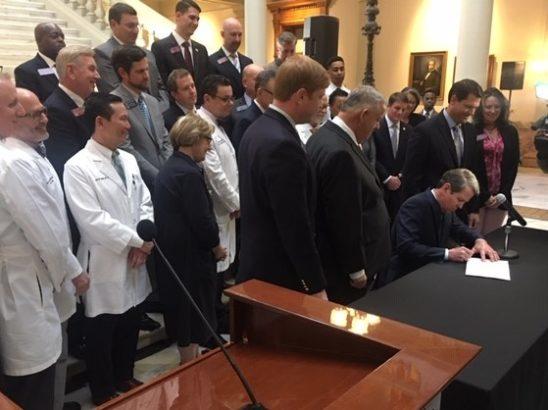

It also mentions, though briefly, the Medicaid waiver plan championed by Gov. Brian Kemp. That plan to extend coverage to more low-income adults is scheduled to launch July 1, but the Biden administration has voiced strong objections to it and could pull the approval that the Trump administration gave to the plan.

In a single short paragraph, the new state report says the waiver plan “would allow approximately 200,000 single, low-income adults to qualify for Medicaid.” But there are eligibility requirements that must be met to gain coverage, including working or being involved in other specified activities at least 80 hours a month. Those requirements would keep the number enrolled at about 50,000, according to projections from the Kemp administration.

And it remains unclear whether the feds will allow the Kemp plan to happen at all.

Trying To Reach The Right Populations

Medicaid and PeachCare provide health insurance to about 2 million low-income Georgians, with the large majority of members getting coverage under health insurance companies. Those companies are paid about $4 billion annually to provide those services.

State Medicaid agencies must publish quality strategies every three years, according to federal regulations. Georgia’s last previous report was published five years ago, in 2016.

The new report outlines a “more population-based” approach to Medicaid, said Fiona Roberts, spokeswoman for the Department of Community Health, which released the report.

The agency says it will collect and analyze data on health disparities – along race, ethnic, gender, language, and special-needs lines – starting this year. Community Health plans to share the data with the Medicaid insurance companies and “create quality improvement activities to address the identified disparities,” according to the report.

“We’re really excited to see the state engaging the [insurance companies] to look at and improve outcomes by race, ethnicity, gender, special needs, etc.,” said Melissa Haberlen DeWolf of Voices for Georgia’s Children, an advocacy organization that focuses on child well-being in the state.

“Georgia has some stark racial and ethnic disparities in our health outcomes, and in order to make any meaningful improvements, the largest health insurer of children in our state [Medicaid] has to play a central role,” said Haberlen DeWolf.

The nearly half of Georgia children who rely on Medicaid or PeachCare for Kids “deserve the same quality of and access to health care as children who are privately insured,” said Haberlen DeWolf.

Strategies to improve Medicaid patients’ access to care include case management, ensuring transportation to appointments, screening patients for lack of proper food or housing and vulnerability to violence, and translation services for those with language barriers, according to the report.

In the past few decades, Georgia has gained many new residents who are not native speakers of English.

The report’s focus on translation is “definitely just a starting point” on cultural competence in health care, said Haberlen DeWolf.

“It’s also critical that families are engaged in a culturally appropriate way – this is particularly important for behavioral health, but really for all medical services. In order to provide true, quality care, one needs to understand a patient’s culture, how to connect with them, and how to best care for them within that context,” she said.

In other words, language translation is not enough.

Saving New Mothers And Infants

Georgia’s Medicaid agency says it aims to decrease maternal mortality rates by 3 percent by the end of 2023. Maternal mortality is defined by the CDC as the death of a woman while she is pregnant or within one year of the end of the pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management. These death rates are unusually high in Georgia.

The agency also aims to improve the state’s prenatal and postpartum care to the national 50th percentile rate. And it wants to decrease Georgia’s rate of low-birth-weight infant deliveries, the report says.

All three of these rates worsened between 2014 and 2019. (Georgia Health News collected and analyzed these measures in a February article.)

Several other measures showed worrisome trends, including immunization rates for children, and blood pressure and diabetes care rates.

One measure that improved was well-child visits. Another was follow-up for children who have been prescribed ADHD drugs.

Working with the Medicaid population brings a share of special challenges listed in the report. These include transitory populations, lack of health literacy, and high “no-show rates” for medical appointments. But these challenges are “neither new nor unique to Georgia,” said Haberlen DeWolf.

“For the next round of performance goals, we really hope to see the [insurance companies] tackling these challenges with creative, community-informed solutions,” she said.

Laura Colbert, executive director of the group Georgians for a Healthy Future, said it’s important to hold the companies accountable, and for the state to be ‘’creative, forward-looking, and progressive when it comes to Medicaid payment and policies.”

“DCH has made meaningful strides in the last several years that give me reason to think it can rise to the occasion and embody all three of these qualities if given support from the governor and Legislature,” said Colbert.

The insurance companies can be charged up to $100,000 per violation for failure to deliver effective services to improve low-birth-weight rates.

In fact, the report now includes a list of potential penalties for the insurance companies if they don’t meet certain targets.

“I’ve never seen those accountability measures so clearly, publicly stated,” said Haberlen DeWolf of the Voices group.

“We will be watching with great interest to make sure that, when need be, accountability occurs, and hope that the plan’s implementation occurs with transparency,” she said.

There is also a limited plan in place to tie the payment an insurer receives to its performance, according to the new report.

This applies only to the Georgia Families 360 program, which covers a small but vulnerable group of 27,000 children and young adults, especially those in foster care and some parts of the juvenile justice system. Only one insurance company – Amerigroup 360 – works with this population.

Under the “value-based payment” plan, up to 5 percent of payments to that company could be withheld depending on how it met certain “performance targets.”

The report does not provide details on what those targets are. It does say that performance will be reviewed in 2022.

The public comment period on the strategy is open until April 30. To comment, contact: Dr. Gloria Beecher (Gloria.beecher1@dch.ga.gov).

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Health News.