Section Branding

Header Content

The Ant-icipation Is Over: 'Juan Hormiga' Is Here!

Primary Content

I've been watching a lot of foreign-language television lately. (Confession: I do love good television.) It seems that all of a sudden there is a plethora of non-American shows to watch, and it's wonderful. One night I may watch a Danish show, another night a show from Sweden or Mexico. The style is so different from what one normally finds on American television that I can't get enough. And luckily for me, the world of children's books is following suit.

I had never heard of Gustavo Roldán before the book Juan Hormiga arrived at my door. I didn't know about his El erizo, the story of a hedgehog who needed an elephant's help getting an apple off a tree, or Cómo reconocer a un monstruo, that teaches kids to recognize monsters (they may have a nose which looks like an eggplant). No, the Argentinian-born, Barcelona-based Roldán is an author I didn't know, not even a little.

Then along came Juan Hormiga.

While Roldán's books have been translated into many languages, English, at least American English, has not been one of them until now. Published in its original Spanish in 2012, Juan Hormiga is finally available in English, and thank goodness!

Juan Hormiga, translated by Robert Croll, is, in a word, hilarious. Juan Hormiga is the one red ant among thousands of black ants, but it's not his being red that sets him apart from the rest of the colony. While every other ant is as industrious as you might expect, busily collecting food or digging tunnels, that's just not Juan Hormiga's forté. No, Juan has some extra-special talents:

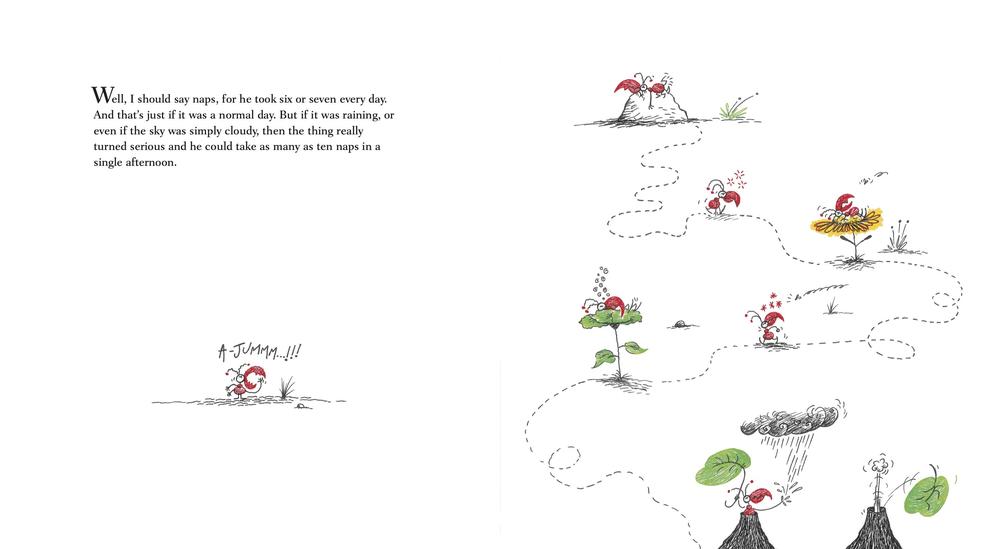

"If there was one way in which Juan Hormiga was second to none, it was his way of taking a nap.

Well, I should say naps, for he took six or seven every day. And that's just if it was a normal day."

To quote Peter Falk in The Princess Bride, isn't that a wonderful beginning?

But it gets better.

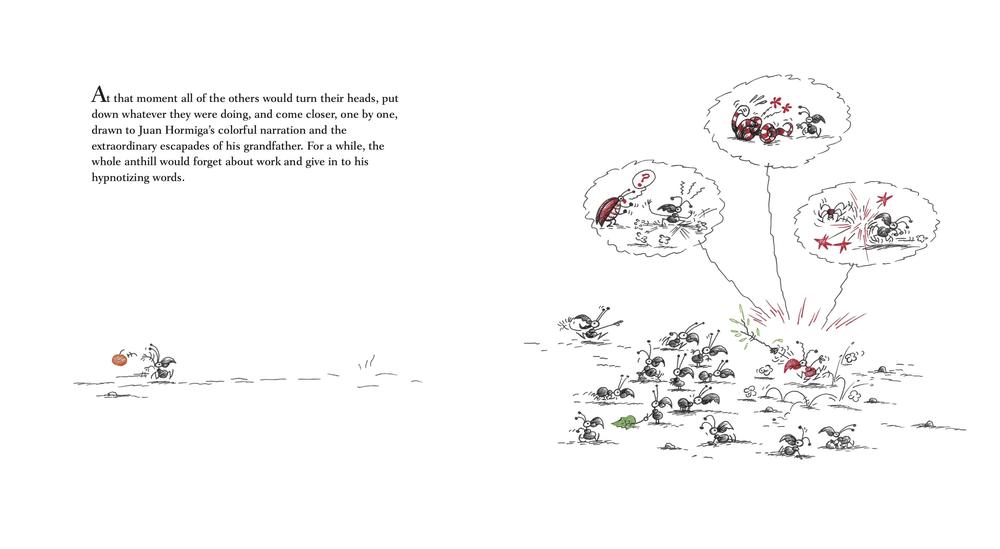

All those industrious black ants could have resented the lazy Juan Hormiga. They could have denied him tunnel privileges or picnic scraps, but no, the other ants "didn't seem to mind too much." Naps are not Juan's only talent: He's also a storyteller, a born storyteller. Juan is such a good storyteller that whenever he starts to tell a story, which seems to be whenever he's awake, all the other ants forget about their work and come close to listen to Juan recount his grandfather's adventures far beyond the world of the anthill.

Roldán's illustrations — whimsical, charming, fun, adorable, the whole nine yards of illustration and description — show wide-eyed ants at rapt attention as Juan Hormiga bounces and dances, his grandfather in bubbles above his head, fighting snakes and beetles and spiders (always winning, of course). How can the ants possibly work when Juan is telling such wonderful stories?

But alas, soon the ants have to tell stories for themselves.

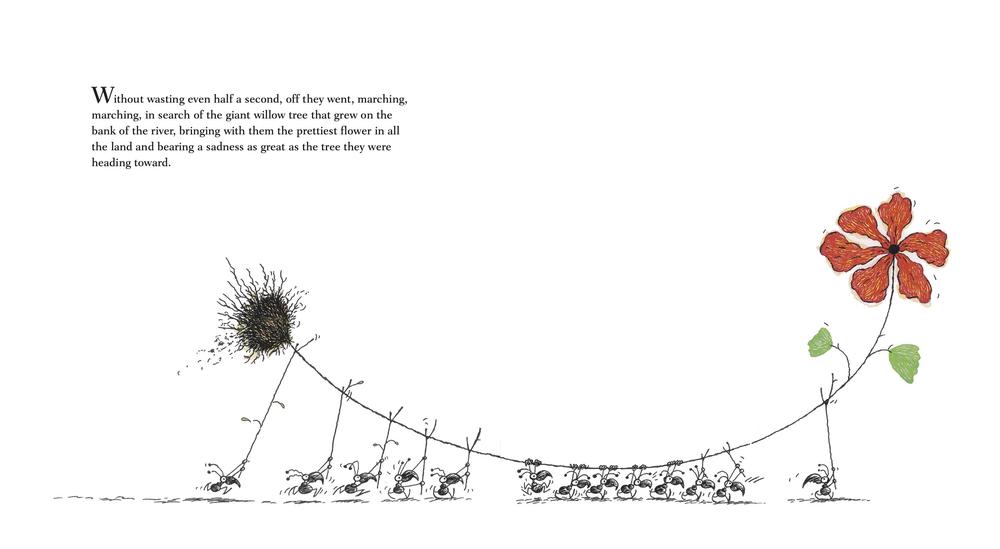

Juan Hormiga decides he's not satisfied with his grandfather's adventures — he wants to tell stories of his own, so he sets out from the anthill with a determined announcement of his departure and a little cloth bundle of food.

Oh, Juan is gone for a long time! Hours and hours, he is gone. The other ants speculate on where he is and what he is doing. Is he crossing the river? Is he dangling from a spider's thread? Oh, Juan Hormiga, you are terribly brave, and strong, and determined.

It's at this point at which my kids start bouncing up and down on their beds. Go, Juan, go!

But Juan! (this is the point at which my kids get concerned, no matter how many times we've read the story). There is a huge rainstorm coming!

Back at the colony, the ants, seeking high ground to escape the rising waters, fear the worst for Juan. He's out there, somewhere in the world on his adventures, and only the worst must have befallen him.

"The ants took a moment of silence in homage to the valiant Juan Hormiga."

There are a lot of pages left in the book after this, so don't worry too much for Juan Hormiga; his naps come in handy.

It's hard to put into words what makes children's stories from other countries different from American children's stories. Certainly, European fairy tales historically have had a much darker tone than American fairy tales, as have fairy tales from other regions. There tends to be quite a bit more of the fantastical in the English tradition of writing for children, for sure. Language, cultural, and historical context have a lot to do with what gives stories their flavor, and it's no different with the Spanish Juan Hormiga.

Does Juan Hormiga seem rooted in a fable-telling tradition? Yes. Does it seem born of a culture in which nap-taking is not frowned upon? Absolutely. (That's definitely not American.)

But is Juan Hormiga still familiar? Yes. Roldán calls it his answer to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which his mother read to him when he was a child, and he follows the tradition of his own father, who told him and his sister stories of his own childhood adventures.

It's been years and years since I've read Tom Sawyer, but what I do know is that Juan Hormiga is a jewel of a story. It has everything my kids and I want from a book: silliness, adventure (kind of), daring (kind of), a cliffhanger (kind of), a satisfying ending (truly!). And best of all, I can finally read it!

Juanita Giles is the founder and executive director of the Virginia Children's Book Festival. She lives on a farm in Southern Virginia with her family.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.