Caption

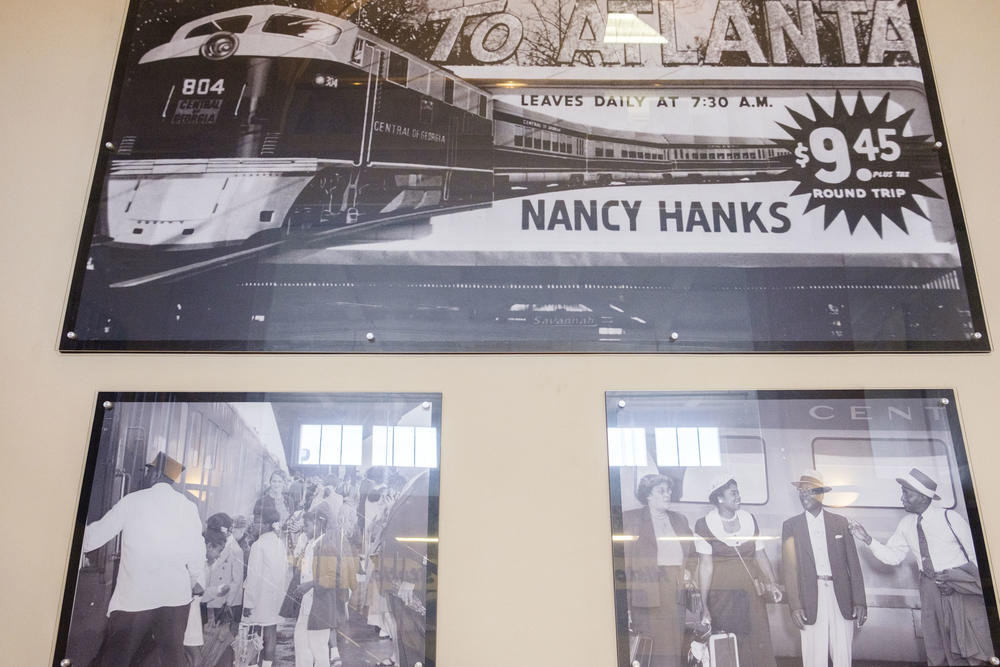

The waiting area of Terminal Station in Macon. Until the 1960s, this is where passengers would have waited to board a train called the Nancy Hanks, running north to Atlanta or southeast to Savannah.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

The waiting area of Terminal Station in Macon. Until the 1960s, this is where passengers would have waited to board a train called the Nancy Hanks, running north to Atlanta or southeast to Savannah.

Stu Nicholson has been trying for decades without success to get Amtrak — or any other passenger rail service — to come to Columbus, Ohio.

As director of All Aboard Ohio, a passenger rail advocacy group, Nicholson helped explore possibilities, like creating a new route from Chicago to Pittsburgh, with Columbus in the middle.

But for now, Columbus, a city with 878,000 people, the second-largest city in the Midwest, has no passenger rail service. It doesn’t even have a station.

That could soon change. A plan Amtrak is floating would not just restore passenger service to Columbus, but also across Ohio and spanning the U.S., from Colorado to Florida to Georgia to Wisconsin.

Georgia’s latest passenger rail plan shows a line stretching from Savannah, through Atlanta and northward to Nashville. It also plots out a line for high-speed rail from Atlanta to Chattanooga, although that technology is falling out of favor.

Archive photos of the last generation of passenger rail between Atlanta, Macon and Savannah adorn the walls of Terminal Station in Macon.

Whether the plan might become reality has yet to be seen, but it’s sparked hope in states and cities that, like Columbus, are now passenger rail deserts.

Amtrak is pitching a vast expansion of its network of routes less than 500 miles long. The railroad wants to create 39 new routes, improve 25 current routes, serve as many as 166 new cities and add shorter-haul routes to 16 new states.

It estimates that it could increase its yearly number of passenger trips by 20 million by 2035, on top of the record high it set in 2019 of 32.5 million.

And on Friday, America’s No. 1 rail passenger, President Joe Biden is traveling to Philadelphia to help Amtrak celebrate its 50th anniversary and no doubt talk up the benefits of passenger rail. Biden, nicknamed “Amtrak Joe,” rode the train back and forth daily to his home in Wilmington, Del., while a member of the U.S. Senate.

“This is the very first time that Amtrak has ever gone on offense in their 50-year history,” Nicholson says. Amtrak has had to defend against budget hawks who wanted to cut its subsidies or eliminate them altogether, he says.

“Consequently, they’ve never had enough of a budget to go out and do what really needs to be done for a long time, which is a major expansion of service.”

Under Amtrak’s vision for Ohio, the route connecting Cleveland in the north to Columbus in central Ohio and Cincinnati in southern Ohio would finally be completed. The number of trains coming to Cincinnati, Cleveland and Toledo every day would increase on other routes, too.

“This was a major pick-your-jaw-off-the-floor moment for a lot of us that have been around passenger rail advocacy … when we found out what Amtrak was planning and what they were proposing,” Nicholson says.

Indeed, Amtrak’s expansion plans set off a flurry of excitement around the country, as people pored over a route map that the railroad produced of potential new routes.

The publicly owned railroad, of course, also benefits from the fact that its most famous passenger — Biden — has proposed a massive infrastructure package that could pay for many of the improvements Amtrak is pushing.

The reason advocates like Nicholson are excited about Amtrak’s proposal, though, goes beyond just the cities and lines on its much-tweeted map. The railroad appears to be trying to avoid some of the pitfalls that stymied previous expansion plans, particularly under President Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus package.

So, for example, the plan does not call for bullet trains or other forms of high-speed rail. The ongoing drama over California’s high speed rail project has tarnished the public’s view of that technology.

Private companies trying to build faster projects in Florida and Texas have also run into opposition from residents who live along their routes but not close enough to a station to use it, something that’s far less of a problem for regional rail.

Amtrak also wants to be in charge of — and foot the bill for — any construction that would be needed to add more routes.

Importantly, it would also pay for the costs of operating the trains for the first two years, before gradually transitioning to a 50-50 split with the state governments along the route. Political leaders have used the issue of state subsidies to oppose Obama-era rail expansions.

Former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, for example, came to power by campaigning against the construction of a route between Madison and Milwaukee. The federal government agreed to pay the $810 million to build the new route, but Walker objected to the state being on the hook for about $7.5 million a year to support its operations.

Nicholson says Amtrak’s plan for bearing the operational costs for the first few years will build political support for the new services and give state governments time to develop a way to pay for it.

In a place like Columbus, for example, state and local leaders could work out a way to capture some of the value created by a new rail station and nearby developments to help pay for the state’s share of the rail service.

Amtrak’s proposed improvements also include many expansions that state and local officials have already been advocating.

The plan, for example, envisions rail service connecting Denver to Colorado Springs and Pueblo in the south and Cheyenne, Wyo., in the north. That route is strikingly similar to a proposal that lawmakers and state transportation officials are studying to introduce a Front Range passenger rail system.

The overall Amtrak proposal includes all three rail projects stopped by Republican governors in the Obama era: Ohio’s Cleveland-Columbus-Cincinnati corridor; a route between Orlando and Tampa in Florida; and the Milwaukee-to-Madison leg in Wisconsin.

The main reason Amtrak’s proposal is so salient right now is because of Biden’s infrastructure push. The president’s American Jobs Plan would include $80 billion to help Amtrak catch up on overdue repairs, replace outdated equipment, make upgrades along its Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington, D.C., and fund its expansion efforts.

The Amtrak proposal is in line with the Biden plan, but the two are separate for now. The White House has only provided broad outlines for how it wants to dole out money in its infrastructure package. It hasn’t yet provided the kind of details Amtrak released, and the final outcome would also likely be shaped by Congress.

“I keep trying to tell people [Amtrak’s] map is not THE map. It is A map. There was a totally different map last September, and there’s likely to be a different one in the next few weeks or months,” says Jim Matthews, the president and CEO of the Rail Passengers Association, a national advocacy group. “There are a lot of proposals. They are all very generous.”

There will also be several chances for Congress to take on Amtrak funding, he notes. The first is whatever it does with Biden’s infrastructure plan.

But Congress will also have to reauthorize the multi-year law that pays for highways, transit and Amtrak, which expires in September. So lawmakers could address it when they handle that bill, too.

Matthews says that Congress has become more receptive to funding Amtrak in just the last few years. As recently as 2015, he says, Amtrak was still fighting lawmakers who wanted to completely eliminate its subsidy.

“The steely knives were out,” he says. “I think we managed to shift the conversation in subsequent Congresses… The conversation among Amtrak critics went from ‘Why do we have Amtrak?’ to ‘Why is Amtrak so bad?’ I know that sounds a little strange, but, honestly, that’s a win.”

The freight rail industry also seems open to expanded Amtrak service, an important consideration because private freight rail companies own most of the track Amtrak trains travel on. (The federal government took over passenger rail service from the private railroads 50 years ago and created Amtrak, as a way to prop up what was then a financially beleaguered rail industry.)

The Association of American Railroads, which represents freight rail companies, says that any passenger rail operations on privately owned tracks should be safe, should not impede freight rail operations, should compensate the freight companies and should have arrangements tailored for each route.

The industry backed Biden’s call for better infrastructure, but it strongly opposes Biden’s suggested way of paying for it with higher corporate taxes.

“Railroads would urge the administration and Congress to abandon these divisive, unrelated funding sources and instead work toward bipartisan solutions to restore the Highway Trust Fund to a true user-pays system,” AAR President and CEO Ian Jefferies said in a statement.

The freight railroads have encouraged Congress to shore up regular funding for Amtrak by moving from fuel taxes to a system where motor vehicle owners are charged for the number of miles they drive, as well as the weight of the vehicles driven.

The railroads have also called on Congress to impose an emissions surcharge on motor vehicles, which could generate money specifically dedicated to funding passenger rail.

“A reliable passenger rail network is the most environmentally-friendly mode to move people over land and is essential to helping address transportation-related emissions,” the group wrote in a recent paper on freight railroads and climate change.

“Intercity passenger rail is the only mode of passenger transportation in the United States that does not receive any dedicated federal funding through a trust fund, leaving Amtrak completely dependent upon annual discretionary appropriations. This fiscal uncertainty makes it difficult for Amtrak to plan its operations and capital needs for the long term,” it added.

Imposing extra fees on heavy vehicles and vehicles that produce more greenhouse gas pollution would make transporting goods by trucks more expensive, and could make freight rail a more attractive option.

Meanwhile, in Columbus, local leaders think they have a compelling case for adding new service if Amtrak can find the funding to do so. That’s true whether the trains go to Cleveland and Cincinnati or to Chicago and Pittsburgh.

“The Columbus region is one of the largest regions in the nation that is not serviced by passenger rail today,” says Thea Ewing, the director of transportation and infrastructure development at the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission.

“We are a growing region too. We’re talking about an area that’s thriving… We are a market that stands ready to receive and make the best of it.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Recorder.