Caption

Voters wait in line at the Macon-Bibb County Board of Elections during early voting in the 2020 Presidential Election.

Credit: Grant Blankenship

Voters wait in line at the Macon-Bibb County Board of Elections during early voting in the 2020 Presidential Election.

While new U.S. Census data shows Georgia added more than a million people over the last decade, an even larger change in registered voters — and who they vote for — will be key considerations when lawmakers begin assigning residents into new voting districts this fall.

Population figures released this week provide a starting point for determining how Georgia’s 10,711,908 people will be split up into legislative and Congressional districts of equal proportions.

But the political leanings of the state’s 7.6 million active voters — including the five million that flocked to the polls last November — will be an equally important metric in deciding where lines are drawn.

At stake is Georgia’s political future, as these new boundaries can make purple seats redder, vulnerable incumbents safer and will decide who controls the state legislature and, potentially, Congress.

Along with the surge in population, Georgia’s voter rolls have swelled dramatically over the past decade, largely with non-white and suburban voters who have turned a reliably red state into a purple battleground that narrowly elected Joe Biden and two Democratic U.S. senators.

Republican lawmakers in control of the redistricting process will have to balance rapidly diversifying metro Atlanta suburbs with slow-growing rural communities in an effort to preserve their power for the next 10 years.

Bryan Tyson, an attorney who specializes in redistricting and election law for the firm Taylor English Duma, told GPB News earlier this week that rural counties that haven’t kept pace in growth with the metro areas will likely see bigger districts that weaken their influence — especially since districts have equally sized populations, not amounts of voters.

"It's like squeezing a balloon — you squeeze on one side, it's going to pop out the other side," he said. "So if there's a lower population in one part of the state, it's going to have to grow north, which means Atlanta is going to continue to pull districts towards it."

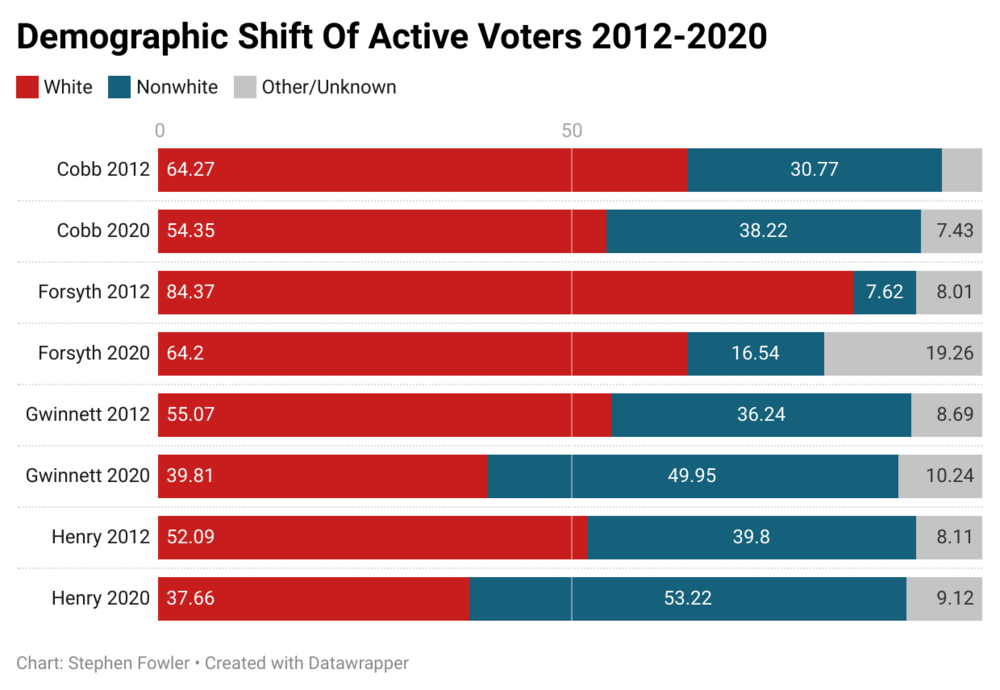

Since 2012, Georgia's voter rolls have grown by 42% and the share of white voters has dropped about 7%.

According to a GPB News/Georgia News Lab analysis, voter registration in Georgia soared to over 7.6 million active voters, adding more than 2.25 million people since 2012, the year of the first elections held on the current district maps. That nearly 42% increase was driven by a surge in nonwhite voters flocking to Atlanta’s suburbs, and in part by the state’s 2016 “Motor Voter” law that automatically registers voters when they interact with the Department of Driver Services.

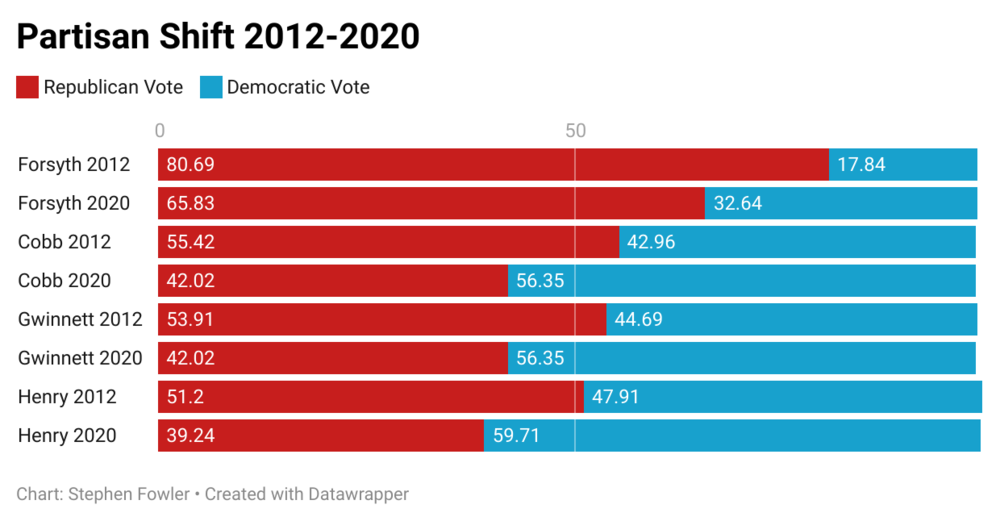

As a result of the influx, three historically Republican metro Atlanta counties — Gwinnett, Cobb and Henry — flipped blue in the 2016 presidential race and by 2020 provided enough votes to help President Joe Biden narrowly win the state and send two Democrats to the U.S. Senate in a January runoff.

Statewide, the share of white voters has fallen nearly 7% since 2012, down to just 52.6% in November 2020. The share of Black voters, a reliable backbone of Democratic support in Georgia, has stayed steady at 30%.

The Secretary of State’s office data on voter demographics used in this analysis includes turnout breakdowns by race and gender, including 146,385 voters classified as “Other” and 688,641 where the race is “Unknown.”

Since 2012, Cobb, Gwinnett and Henry Counties have gone from solid Republican counties to voting for Democrats.

The most notable increase in active registered voters was in Gwinnett County, the second-largest voter population in the state. Voter rolls there grew nearly 57% to more than 622,000. The share of white voters in Gwinnett dropped from 55% to 40% from 2012 to 2020, while the total number of active Hispanic and Asian-Pacific Islander voters each tripled.

Gwinnett’s politics have also shifted, swinging from 54% Republican in the 2012 presidential race to supporting Joe Biden by more than 58% in 2020 and flipping Georgia’s 7th Congressional District, which sits mostly in Gwinnett. The Duluth-based state Senate seat once held by current Georgia Republican Party Chairman David Shafer at the start of the decade is now represented by Democrat Michelle Au, Georgia’s first Asian American state senator.

South of Atlanta, Henry County’s voter rolls grew nearly 50% from 2012 and 2020 to more than 181,000. The number of Black voters nearly doubled in that time as the share of white voters fell by 14%, from a slim majority to just 38% by last fall.

After voting for Mitt Romney by three points in 2012, then Hillary Clinton by four in 2016, Henry shifted to the left more than any other county in the country, voting for Biden by nearly 20 points in 2020.

Cobb County, home base to former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich and long emblematic of Georgia’s Republican-leaning suburbs, saw voter registration increase more than a third since 2012, up to 561,000 people. In that time, the number of nonwhite voters increased by nearly 82% while the number of white registered voters increased only 24%.

The new voters have altered Cobb’s politics as well. In 2012, Romney took 55% of the county’s vote. In 2020, Biden won with 56%.

MORE: Georgia Adds 1 Million Residents, Keeps 14 House Seats After 2020 Census

Within these growing metro counties, precinct-level voter demographics give a clearer picture of how things are changing and where. Of the 10 Gwinnett precincts that saw the largest percentage growth in active voters since 2012, nine are in majority-nonwhite neighborhoods. Much of the growth has been concentrated between Buford Highway and the Interstate 85 corridor in Norcross, Peachtree Corners and Duluth, with already-Democratic areas growing increasingly blue.

Baycreek G, a precinct just outside of Grayson, went from voting 58-41 for Republicans in the 2012 presidential race to 70% Demcoratic in 2020, a 29-point shift. Harbins A, a Dacula precinct split between Democrat Donna McLeod and Republican Chuck Efstration’s House districts, also became majority nonwhite and flipped Democratic over the last eight years. And Sugar Hill A, in Buford, nearly doubled in size, swung 13 points to the left and is poised to flip blue in future elections.

Smyrna 7A in Cobb County went from nearly 80% white and 63% Republican in 2012 to majority nonwhite and supporting Democrats by nearly a three-to-one margin, thanks to a voter population that more than doubled to nearly 6,700.

In Henry County, a surge in Black voter registration, led by the Cotton Indian precinct in Stockbridge, the Lowes precinct in Locust Grove and the McDonough precinct, drove the southern suburb’s change in voting behavior.

Beyond the three counties that flipped, much of Georgia’s population and voter growth has come in the northern exurbs of Forsyth and Cherokee counties, creating the possibility of new state House and Senate seats being created in those areas — likely replacing solid Republican districts in south Georgia with rapidly diversifying communities in metro areas.

Forsyth’s voter rolls grew by 67% since 2012, more than any other metropolitan county. The number of nonwhite voters grew fivefold in that time, including a nearly 600% increase in Asian Pacific Islander voters. The share of white voters in Forsyth dropped by 20% in that time, and the county’s solid-red reputation has faded over the years as well, with Forsyth dropping from 80% Republican in 2012 to 66% in 2020.

The once reliably Republican Brandywine precinct in the southwest corner of the county, next to Alpharetta, voted Democratic in the 2020 election. Next door, the Big Creek precinct has grown from 6,400 to 11,800 active voters, driven by an 8% increase in Asian Pacific Islander share of the electorate. It has shifted nearly 21 points to the left over the last eight years.

In Cherokee County, the white share of the vote dropped from 84% in 2012, to 77% in 2020, as the number of nonwhite voters doubled. After Mitt Romney won Cherokee with 78% of the vote in 2012, Donald Trump won with 69% in 2020.

RELATED: How To Be A Redistricting Watchdog

Just under half of the state’s 7.6 million active voters live in 115 counties that saw their voter rolls grow at a rate slower than the average, primarily in rural areas across middle and south Georgia. The remaining 44 counties account for 60% of the state’s registered voter growth since 2012 and include most of North Georgia, metro areas around Atlanta and Savannah and Valdosta.

With Georgia narrowly flipping in the 2020 election cycle and a contentious race in 2022 that will feature every statewide elected office, the legislature and a U.S. Senate seat, the precincts in which voters are located — and who they vote for — will be crucial factors considered by lawmakers as they redraw the maps that will determine who controls state government moving forward.