Section Branding

Header Content

Massachusetts Pioneers Rules For Police Use Of Facial Recognition Tech

Primary Content

Massachusetts lawmakers passed one of the first state-wide restrictions of facial recognition as part of a sweeping police reform law.

The new law sets limits on how police use the technology in criminal investigations. It's one of the first attempts to find middle ground when regulating this technology, but not all privacy advocates agree that regulation is the right step.

Democratic state Sen. Sonia Chang-Díaz was one of the leaders behind this push for criminal justice reform.

"There's some pretty sensible guardrails that can be put around the use of facial surveillance technology while the state does the work of collecting data to understand and get a more fulsome picture of how the technology is being used currently," said Chang-Diaz.

Before the legislation, police could run a state-wide facial recognition search simply by emailing a photograph to the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles (RMV). Law enforcement typically requested searches for suspects for misdemeanor and felony level offenses like fraud, burglary, larceny, identity theft and sexual assault.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts discovered this when the organization filed hundreds of public records requests in an attempt to get a better understanding of how law enforcement was using facial recognition technology. The organization's executive director, Carol Rose, says the records showed police had been using the RMV for searches with little oversight. Rose says that information should be tracked and disclosed to defense counsel when it's used in criminal investigations.

"That's really important because so often this technology is resulting in false positives, and particularly against people of color, because face surveillance technology has a very hard time recognizing black and brown faces."

Police must now have a court order before they can compare images to the database of photos and names held by the RMV, the FBI, or Massachusetts State Police.

"It prevents the use of it by the police when it's not relevant to an investigation, which is an important but fairly low standard. That means [law enforcement] can't track someone in their personal life for personal reasons, like an ex-spouse, and so it prevents the most bald-faced types of potential misuse," said Rose.

While it's a lower bar than the warrant requirement that the ACLU of Massachusetts and other lawmakers had originally pushed for, it's still more restrictions than State Police or FBI face when they use the technology.

The new legislation also requires law enforcement to document their searches and eventually statistics on their searches will be made public. Whether or not the information will be disclosed to defendants is a question that's been put off to future legislation and a new commission.

The new law creates a commission to study due process and facial recognition as well as the technology's ability to identify people of different races, genders and ages and to provide recommendations for future use.

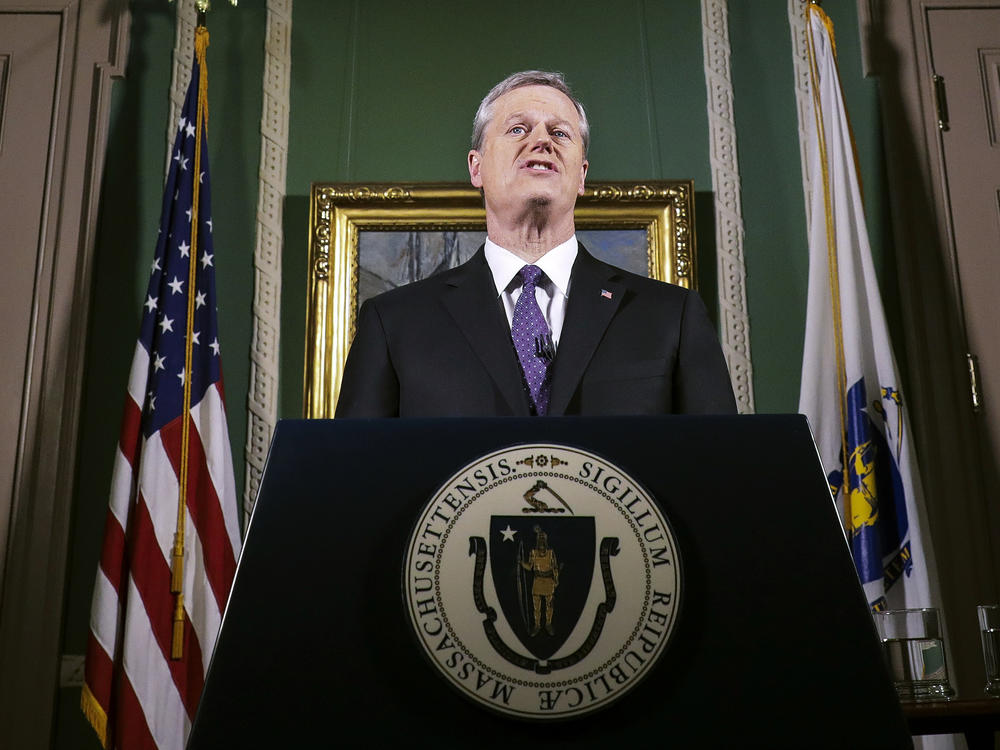

The commission wants to look at what was taken out of the original bill when Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, threatened a veto. The missing requirements included aspects like due process requirements and whether a warrant should be required for a search.

The future of the regulations looked uncertain after Baker came out strongly against facial recognition restrictions specifically.

"I'm not going to sign a bill into law that bans facial recognition," Baker told WBUR in December. In a letter to lawmakers, he said the law "ignores the important role it can play in solving crime."

Chang-Díaz says the original bill was never a ban and included clear instances when law enforcement could use facial recognition technology. Chang-Díaz says she thinks that framing helped the governor loosen restrictions.

"It's just a relatively new issue. There's just not a depth of knowledge about it in the general public," said Chang-Díaz. "There's not a lot of data out there, even for policymakers, about how much is this getting used and in what ways is it getting used by law enforcement."

She says in the absence of that information it's easy for proponents of the technology to use "emotionally charged examples" to support their positions.

These disagreements are part of what makes legislating facial recognition problematic. Baker was quick to point out the tangible benefits. In his defense of the technology, Baker outlined several cases where facial recognition played a key role in solving major crimes.

"If there's something like a child abduction or, God forbid, a murder, we want to utilize every piece of technology that's available to identify the person," said Brian Kyes, president of the Massachusetts Major City Chiefs of Police.

Recently, members of the public used facial recognition to identify suspects in the attack on the Capitol, and it's possible, though not proven, the FBI used the technology as well to sift through video evidence.

Kyes says he has never used facial recognition technology, adding if you talked to 10 different police chiefs you'll probably get 10 different opinions about it. But he says he would hesitate to "shut the door" on a tool that might help law enforcement save a life. He looks forward to the commission's recommendations that the governor and the legislators couldn't agree on.

"Let's really look at this. Let's dig down. Let's see if we can come to a reasonable compromise, and I have all the faith and confidence that the experts will do just that when they put this commission together," said Kyes.

This push and pull between privacy and public safety has led to a patchwork of local regulations across the country. Several cities like San Francisco, Minneapolis and Portland have opted to fully ban law enforcement's use of facial recognition, while a lot of states have no regulations at all.

Massachusetts state Rep. David Rogers, a Democrat, says his state is leading the nation with this legislation. He says U.S. Sen. Ed Markey, also a Democrat, called to ask him how the state legislature managed to pass this law. Markey introduced a moratorium for facial recognition at the federal level last summer.

Chang-Díaz says she thinks the groundswell of support for police reform and racial justice played a key role in the lawmakers' ability to regulate this technology. The fact that facial recognition is often found to have significant error rates toward people of color attracted the public's attention and even elicited an op-ed from the Boston Celtics condemning Baker's attempts at removing facial recognition restrictions from the bill.

"Had we not had this moment of reckoning around police brutality, I don't think that the legislature would have taken up issues around facial surveillance policy on its own had there not been this larger push for reform," said Chang-Díaz.

Not all privacy advocates agree that reform is the best path forward for facial recognition. Even though local law enforcement can only contract with the RMV, State Police, and the FBI, nothing is stopping the FBI or State Police from contracting with a private company, which local law enforcement would then have access to. Some of these private companies, like Clearview AI, have received negative attention for searching public photos available online.

The private facial recognition services are unregulated, and prone to the same kinds of accuracy problems found in government systems. Nathan Sheard, associate director of community organizing at the digital civil liberties group Electronic Frontier Foundation, says even if the technology worked it would be a problem.

"We understand that even if the tool worked 100% accurately," Sheard said, "it would still be a significant threat, and we would still need to ban government use of the technology."

Sheard says people should be able to do things like exercise their First Amendment rights, visit medical clinics or have romantic relationships without fear of being tracked by the government.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.