Section Branding

Header Content

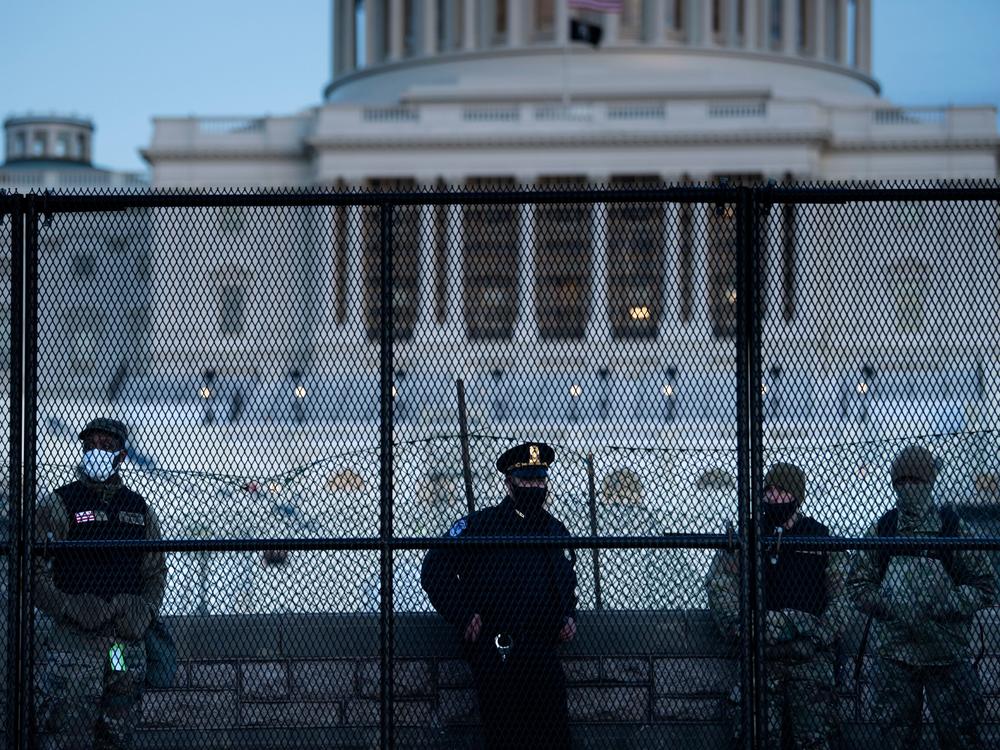

'The Worst I've Seen': Capitol Police Face Scrutiny For Lack Of Transparency

Primary Content

The U.S. Capitol Police have close to 2,000 uniformed officers, more than the Atlanta Police Department.

The agency's annual budget is around half a billion dollars, which is larger than the budget for the entire Detroit Police Department.

But until the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, few Americans were likely aware of the police force dedicated to protecting Congress.

Not anymore.

Capitol Police are now facing widespread criticism for the failure to prevent a pro-Trump mob from storming the building and putting members of Congress, the vice president, congressional staff and their own officers at serious risk. And advocates for government accountability say the Capitol Police's penchant for secrecy only exacerbated these failures.

When it comes to transparency, the Capitol Police are "the worst I've seen," said Daniel Schuman, policy director for the group Demand Progress.

The Capitol Police still have not publicly identified the officer who fatally shot Ashli Babbitt, the 35-year-old Air Force veteran killed during the Capitol riot, or provided a thorough account of the shooting.

Babbitt was seen on video inside the Capitol carrying a backpack, and was flanked by rioters using a pole and a helmet to try force their way past a barricaded door into the Speaker's Lobby. When Babbitt attempted to climb through a smashed window, a Capitol Police officer fired a single shot, killing her. Babbitt, it was later determined, was unarmed.

The Department of Justice announced on April 14 it had closed its investigation into the shooting and would not file any charges against the officer, a decision praised by the officer's attorney. "His actions stopped the mob from breaking through and turning a horrific day in American history into something so much worse," the attorney, Mark Schamel, told NPR in a statement. Schamel noted, "The officer has faced serious and credible death threats since January 6." A spokesperson for the Capitol Police said the officer remains on paid administrative leave.

Babbitt's widower, meanwhile, told NPR he plans to sue the agency, in part, to get more information.

It is "highly unusual" for a police department to keep the identity of an officer involved in a fatal shooting confidential for so long, said Philip M. Stinson, a professor at Bowling Green State University, who tracks police shootings. But, as Stinson added, the Capitol Police aren't "a typical police department."

In practice, the Capitol Police are more of a hybrid police force and protective service. Officers make stops over traffic violations or outstanding warrants near Capitol Hill and sometimes even arrests for marijuana possession at the nearby Union Station. At the same time, the Capitol Police also provide security for members of Congress and their staff.

Unlike many police departments, Capitol Police lack a dedicated civilian oversight board, which could act as a watchdog for the agency, issuing regular reports on uses of force or officer discipline. Capitol Police do have an inspector general, who can investigate problems within the agency. But that office's reports typically remain hidden from the public. The inspector general's reports on the Jan. 6 attack have still not been made publicly available.

While police departments across the country have entire units dedicated to answering requests for public records — such as incident reports, arrest statistics, disciplinary records or bodycam footage — Capitol Police are exempt from the federal Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA.

Since the Capitol riot, Capitol Police have taken some steps to change the agency's longstanding reputation for secrecy, including hiring additional staff for the communications office and issuing more public press releases.

But more meaningful changes will likely require Congress to act. Leading members of the House of Representatives told NPR that they are considering a variety of reforms. Advocates said changes are urgently needed, because the absence of transparency creates the potential for problems to fester inside the Capitol Police.

"Policing is a governmental institution. And in a democracy, we do not leave it to government to determine whether government is doing a good job," said Seth Stoughton, a former police officer and professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law. "If the public doesn't know what happened or what steps the agency is planning on taking to ensure that it doesn't happen in the future, then we really don't have any public or democratic accountability there."

Babbitt's family speaks

Aaron Babbitt said he found out that an officer had shot and killed his wife, not from the Capitol Police but from TV news.

His wife, Ashli Babbitt, had traveled to former President Donald Trump's rally in Washington, D.C., alone, while Aaron stayed behind at their home in San Diego. Ashli Babbitt had served more than a decade in the military, and received the Iraq Campaign Medal, indicating she served there in support of the U.S. war. Later, she became an avid Trump supporter. Her social media feed included references to the debunked pro-Trump conspiracy theory QAnon, and she retweeted a message calling for Mike Pence to be charged with treason.

Aaron Babbitt was not keeping close tabs on the events in Washington, he said, when he got a frantic call from a friend. Video of the shooting at the Capitol had been posted online. The friend was "basically in tears, saying they think they'd just seen a video of Ashli, and it looked like she was hurt," Babbitt said.

He said he tried calling hospitals in the Washington area to try to get more information but got nowhere.

Then the news broke on TV.

"I heard the reporter on the TV say that the woman that was shot at the Capitol had passed away," Babbitt said, and his memory gets "pretty dark and hazy after that."

Babbitt said later that night, he spoke with a detective from the Metropolitan Police Department, who eventually confirmed that his wife had died. But "I've never spoken with anyone from the Capitol Police department," he said.

When the Justice Department closed its investigation into the shooting on April 14, Babbitt said he only received the roughly 800-word press release by way of explanation.

Babbitt has retained an attorney, Terrell Roberts III, and has said he plans to sue the Capitol Police. Babbitt said he believes that the officer should not have shot his wife and instead could have used some sort of less-lethal force — whether a baton, pepper spray or stun gun.

Another impetus for the lawsuit, he and his lawyer told NPR, is to obtain additional information about the officer's identity and track record with the Capitol Police.

In general, "we support the police," Babbitt told NPR. "My wife's car is sitting in my driveway right now with two 'thin blue line' stickers on it."

But he called the Capitol Police a "rogue" department and said he primarily blames Congress for the lack of transparency.

"They sit back and they completely refuse to release the name of their own police officer that was involved in a shooting of an unarmed woman," Babbitt said. "It's absolutely ridiculous."

Schamel, the officer's attorney, called Babbitt's planned lawsuit "meritless." He argued in a statement to NPR that it is standard practice for an officer's name to remain confidential when part of a protective detail for top government officials — as opposed to officers who do more typical police work.

"The officer's name is not the story here, and revealing it would add nothing," Schamel said.

"The officer is a decorated veteran with a distinguished, long-term career with the United States Capitol Police," Schamel said, adding, "Thankfully, this was the first time the officer used deadly force in protecting Members of Congress."

The Capitol Police declined to comment on the legal threats brought by Aaron Babbitt and his attorney. But in a statement, the agency said, "The Department is not releasing the officer's name, which is also standard procedure when there are concerns for an officer's safety, as there is in this case."

Potential congressional action

Rep. Rodney Davis of Illinois is one of the leading congressional Republicans overseeing the Capitol Police as the ranking member of the House Administration Committee. Davis was present at the Capitol on Jan. 6 and was also among the members of Congress attacked by a gunman during a practice for the Congressional Baseball Game for Charity in 2017. He praised the rank-and-file Capitol Police officers as heroes. But he's critical of the agency's leadership and said that lack of transparency, and the political nature of the board members who oversee the agency, can cause serious problems.

The Capitol Police Board is made up of three voting members: the House sergeant-at-arms (nominated by the House speaker), the Senate sergeant-at-arms (nominated by the Senate majority leader), and the Architect of the Capitol (nominated by the president).

It is this board, rather than the police chief, that holds much of the power over important day-to-day decisions, from Capitol security to firing officers. But the public almost never hears from the board. And a 2017 report from the Government Accountability Office found that many in Congress also believe "the board does not operate in a transparent manner." Davis said the full board had not testified together before Congress since 1945.

Davis said the testimony of Steven Sund, now the former Capitol Police chief, showed how politics can improperly infect police decision-making.

Sund testified that on Jan. 4, two days before the riot, he went to the House sergeant-at-arms to request National Guard assistance. In Sund's account, the House sergeant-at-arms, then Paul Irving, disagreed. "Mr. Irving stated that he was concerned about the 'optics' of having National Guard present and didn't feel that the intelligence supported it," Sund testified. (Irving disputed that characterization in his own testimony.)

"The optics issue, in my opinion, is 100% politics," Davis said.

The inspector general for the Capitol Police also testified that the agency failed to train members of its Civil Disturbance Unit adequately, neglected to plan fully for the possibility of violence and denied requests to use less-lethal weapons that could have dispersed the rioters.

Davis argued that the Democrats need to push the Capitol Police Board more aggressively for answers about how it spends taxpayer money.

"The Democrats in charge have no intention of putting them in front of us to upset them or to get the answers we need about their agency's role prior to Jan. 6," Davis said.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren of California, the top Democrat on the House Administration Committee, accused Republicans of "grandstanding" and noted that all of the members of the Capitol Police Board in office on Jan. 6 were originally nominated by Republicans.

She and Davis, however, agree about the need for reform.

"I do think transparency should be enhanced both for the public but also for the Congress," Lofgren said. Still, she said she needs to give "careful consideration" to specific proposals.

For example, Lofgren said she is still evaluating whether FOIA should apply to the Capitol Police, and whether the inspector general reports should be made public. She said she had concerns about publicizing sensitive law enforcement information.

One idea Davis and Lofgren agree on is that Capitol Police should largely focus on their protective role and shift away from routine police work.

"They've done drug busts at Union Station, and I'm not sure that's what we need the Capitol Police to be doing," Lofgren said. "I think they need to be more like the Secret Service and less like the Metropolitan Police Department."

Stoughton, the police use-of-force expert at the University of South Carolina, told NPR he's concerned that politics will get in the way of a comprehensive and honest review of the Jan. 6 attack, including the fatal shooting of Ashli Babbitt.

"I'm worried that that's not going to happen in this case, or I'm worried that it's going to happen in a very superficial way," said Stoughton, who also testified for the prosecution in the murder trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

Already, there are signs that a thorough, bipartisan investigation into the Capitol attack — similar to the 9/11 Commission — may be impossible in the current political climate. And that lack of transparency may mean the problems laid bare by the insurrection may not get fully addressed.

"The Capitol Police leadership failed their staff, they failed Congress, and they let the Capitol be overrun by a rabble," said Schuman of Demand Progress. "They didn't put the systems in place where those of us on the outside and those on the inside could hold them accountable, so that when the tests came, they were ready for it."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.