Section Branding

Header Content

Citizens Work To Expose COVID's Real Toll In Nicaragua As Leaders Claim Success

Primary Content

Editor's note: The fight against disinformation has become a facet of nearly every story NPR international correspondents cover, from vaccine hesitancy to authoritarian governments spreading lies. This and other stories by correspondents around the globe focus on different tactics to combat disinformation, the impacts they've had and what other countries might learn from them.

MEXICO CITY — COVID-19 is ravaging Latin America, but one country, Nicaragua, insists it's tackling the pandemic better than any of its neighbors.

There's just one problem: Doctors and critics of the government say Nicaragua's numbers are fake.

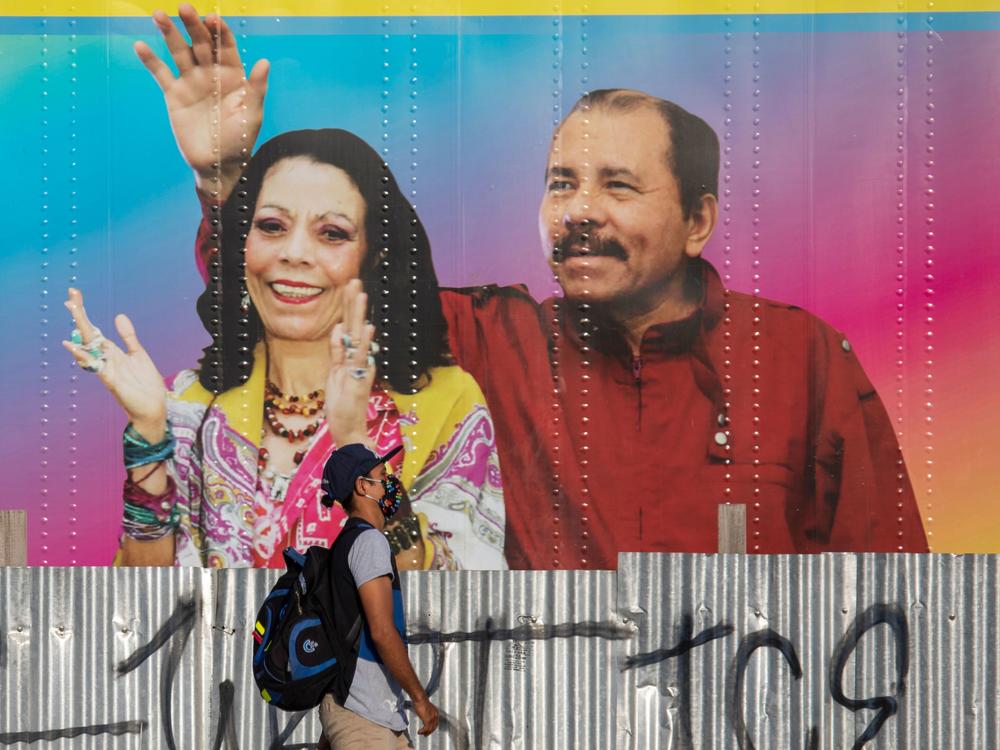

They accuse the Central American country's longtime president, Daniel Ortega, of hiding the pandemic's real toll, and are struggling to get the real numbers and data out to the public.

That's a difficult feat as much of broadcast and print media in Nicaragua is controlled by the government and members of Ortega's family. News reports are filled with Ortega's supposed successes at battling the coronavirus and bringing vaccines to the impoverished country.

"Thanks to God and for the wisdom of our president for his handling of the pandemic," says an elderly woman highlighted in a recent TV report, holding her just vaccinated arm at a clinic.

But contrary to the narrative playing out in state media, Ortega has long downplayed the coronavirus. From the beginning, he has denounced lockdowns and mask mandates. His wife, Rosario Murillo, who is also vice president, encouraged large gatherings. Early in the pandemic, health care workers said they were even barred from wearing protective gear, so as not to alarm the public.

At this year's May 1 International Workers' Day ceremony, the first couple pumped their fists in the air as the international workers anthem played to a small maskless crowd. Ortega brought up the virus — although not the coronavirus.

"The most terrible virus that has infected our planet is the virus of capitalism," said the 75-year-old leader. He blasted rich countries for hoarding vaccines.

Only about 2% of Nicaragua's population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccines donated from Russia, India and the United Nations-backed COVAX program. Last month, the Nicaraguan government secured a $100,000 loan from the Central American Bank for Economic Integration to buy more vaccines.

On paper, the country of 6.5 million people has done an amazing job controlling its coronavirus outbreak. The government said it confirmed 97 new cases of infection in the week up to Tuesday, and 5,649 cumulative cases since the start of the pandemic. It omitted the total fatalities from COVID-19. The World Health Organization puts Nicaragua's official COVID-19 death toll at just 184.

Almost all the other Central American countries, even those with smaller populations than Nicaragua, report deaths in the thousands.

That's where the Observatorio Ciudadano, or Citizen's Observatory, stepped in. Every week through its network of health workers and community activists, the group compiles a detailed list of new cases and deaths it says are from COVID-19.

"The government was deliberately hiding information," says the observatory's spokesperson. NPR has agreed not to use the spokesperson's name, as they fear retaliation from the Ortega government, which has stepped up detentions and attacks against opponents in recent years.

Late in 2020, the legislature — filled with Ortega loyalists — passed a law criminalizing news not authorized by the government. The so-called cybercrime law hands down hefty prison terms for anyone publishing what authorities deem "fake" news on social media or news outlets. This has created a hostile environment for critics and independent news outlets.

The observatory spokesperson says the group knows it's taking a big risk publishing such data but had to "step up and fill this vacuum of information, because we believe that only with solid information can the public be protected and lives saved."

In its latest report for the week up to May 5, the observatory said it counted 15,257 suspected cases and 3,180 suspected deaths due to COVID-19. There is very little coronavirus testing done in Nicaragua, so the observatory relies on the sharing of health records and death certificates to try to verify suspected cases, the spokesperson says.

"But I have to say that every day there are less and less people willing to work with us because of the repression those in the health sector face for speaking out," the spokesperson says.

In May 2020, amid a devastating wave of infections in the country, and a surge of burials done in the dead of night, 700 health workers signed a letter urging the Ortega government to acknowledge the level of community spread of the coronavirus and to impose stricter measures against it. "Deaths could have been avoided," the letter said. "The state cannot continue to evade its responsibility over Nicaraguans' health."

According to Human Rights Watch, three weeks later, the Health Ministry fired as many as 10 public health workers who had signed the letter.

Dr. Carlos Quant, an infectious disease specialist who had worked at the public hospital Manolo Morales in Managua for 20 years, was escorted out the door. "I wasn't even allowed to get my belongings from my office," he tells NPR.

Quant says the government continues putting out false information. "The official figures have no credibility, but the Citizen's Observatory does," he says. The grassroots group's data are reliable and sound an alarm when there is an outbreak, he adds. Independent media use its figure as do private schools and businesses when determining whether to close down or not.

At a busy Managua bus stop, a 25-year-old restaurant worker says it's tough getting good information on the pandemic. He only gives his last name Velázquez for fear of reprisals from the government.

"I don't believe the government, they don't give out exact numbers just vague proclamations," says Velázquez.

Since last October, the government has reported just one COVID-19 death per week. However, an independent investigation of data through August 2020 showed that more than 7,500 deaths than the previous year. The Health Ministry's own data put the number of excess deaths between 2019 and 2020 at nearly 10,000.

NPR's requests for interviews with the health minister and the vice president, who is also the government's spokeswoman, went unanswered.

The spokesperson for the Citizen's Observatory says the group will keep countering the government's disinformation as long as they can.

"It's important to find ways to get the word out about the pandemic," the spokesperson says, "it's the only way we can protect and take care of ourselves."

Wilfredo Miranda Aburto contributed to this report from Managua, Nicaragua.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.