Caption

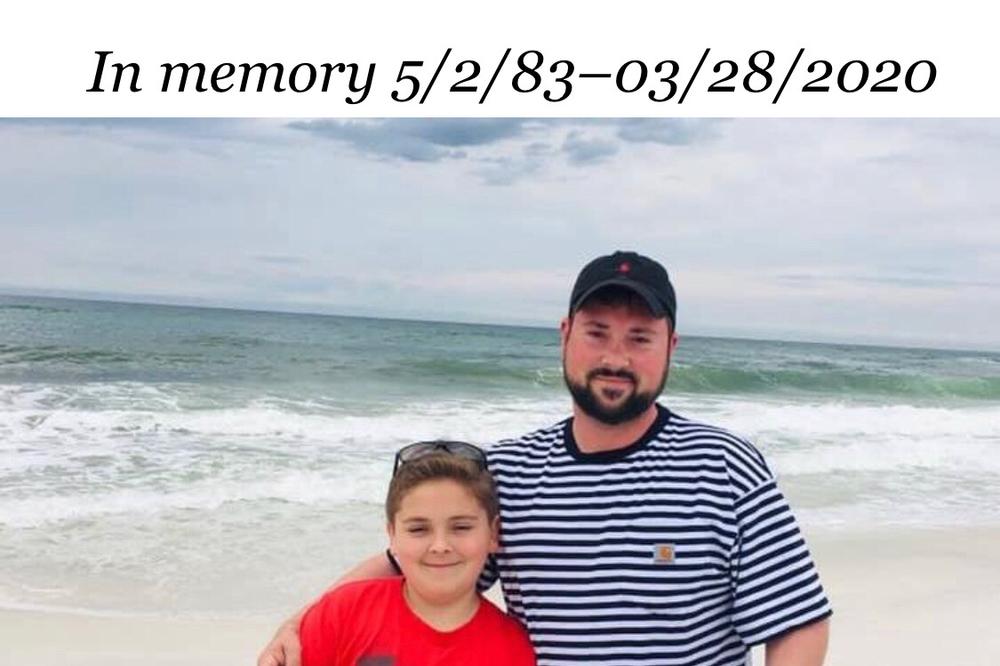

Brandon Little and his sister, Kylee, stand on a shore looking over waves. Brandon's father, James Little, was an early casualty of COVID-19, making Brandon one of many Georgia children who lost a caregiver to the pandemic.

Credit: Contributed