Section Branding

Header Content

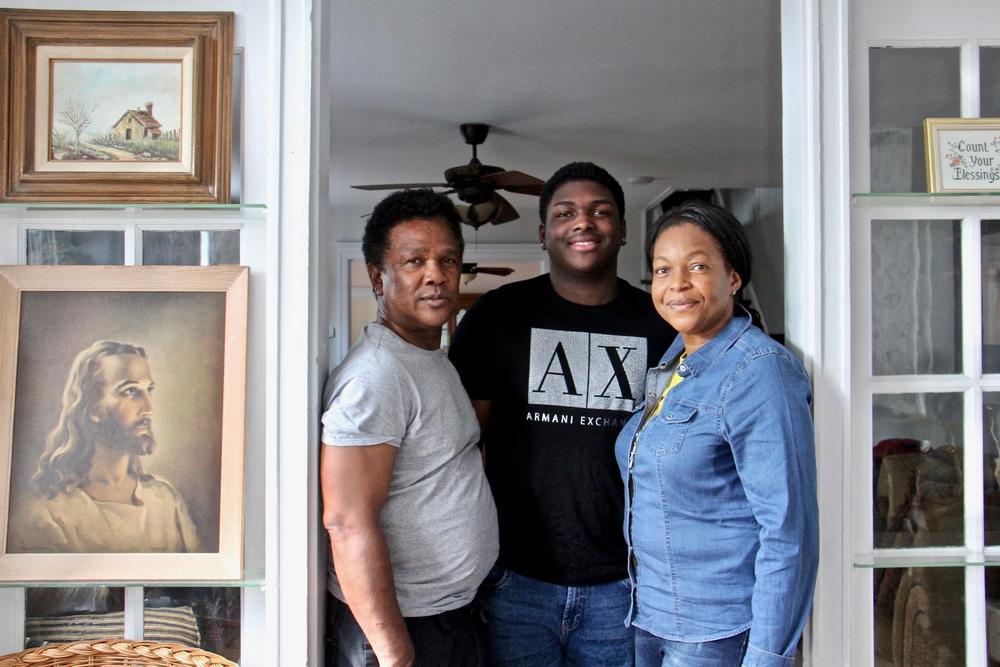

'All Our Opportunity Was Taken Away': Sanctuary Family Slowly Restarts Life

Primary Content

After more than two years living in churches to avoid deportation to Jamaica, Clive and Oneita Thompson noticed some basic life skills had deteriorated.

The first time Oneita went to take out money from an ATM, she said, "'Wait a minute, what do you do again?' ... I truly did not remember how to use my card."

Sometimes, when Oneita wakes up in the morning, she needs to remind herself the family is free.

"I always have to tell myself that it's real," Oneita said last week, about five months after the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) sent a letter to the couple, saying that it would remove the last hurdle for them to get green cards.

Across the United States, dozens of undocumented immigrants took sanctuary in churches during former President Donald Trump's administration, because ICE has guidance to avoid arrests in these and other "sensitive locations." The practice of taking sanctuary occurred under the Obama administration as well, but with fewer people protected from deportation under Trump, the numbers surged.

Those numbers have since dropped significantly, down from a peak of around 50 to just 12 people, according to Church World Service, a group that tracks public sanctuary cases.

For a time, Philadelphia had more undocumented immigrants in sanctuary than any other city, including the Thompsons, according to CWS. As the administration changed priorities or their individual immigration cases advanced, all three Philadelphia families walked free.

The Thompsons' experience shows how even when an immigrant succeeds in staying in the United States by taking sanctuary, the process can be a setback in years of work establishing a secure life here.

Before taking sanctuary in 2018, the couple had spent 14 years in the United States, growing a family and their careers in a small town in southern New Jersey.

They had fled Jamaica after Oneita's brother was killed and their farm was burned. In Cedarville, N.J., they put down roots — Clive worked at a dairy factory and packaging plant and Oneita at a nursing home — but the U.S. government never granted their asylum requests. Rather than leave the country when ordered to, they spent 843 days hiding out in two churches.

While in sanctuary, the Thompsons qualified for a green card through family sponsorship, but it didn't automatically grant them freedom. Now, restarting their lives after two years of virtual house arrest, they've come to find new challenges.

"All our opportunity was taken away," Clive said. "How are we going to start life back over again? It was like a puzzle."

That puzzle is still missing some of its old pieces. Oneita had been taking classes towards becoming a registered nurse when the family went into hiding. Now, many of those credits have lapsed and her nursing assistant license has expired.

"Sometimes I look online, and I saw like people who was going to school with me and they already graduated," she said. "It just feels terrible."

Clive's and Oneita's work permits and driver's licenses have also not been restored.

Even though ICE now supports their path to a permanent residency, a different agency is responsible for handling their green card application — the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. The USCIS website shows backlogs of one-to-two years for processing green card applications, and wait times anywhere from two to 12 months for work authorization applications.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the agency closed its offices and suspended certain services, moves which immigration advocates say contributed to more people losing status and fewer people naturalizing.

"The U.S. immigration is not set up to let people work while they're waiting for paperwork," said Peter Pedemonti, co-founder and director of New Sanctuary Movement, the group which helped place the Thompsons in sanctuary and supported their efforts to win freedom. In some cases, that means immigrants must work under the table or depend on the support of others while their applications move through the system.

Leaving sanctuary, he continued, "it's not a magic fairytale ending."

Before moving out, each family makes a fundraising plan, according to Pedemonti, based on the costs they will have when leaving.

The Thompsons have their own email list of supporters, and a robust fundraising network built up over two years in sanctuary. They also hold fundraisers where they cook Jamaican dinners for a crowd. During the pandemic, that turned into takeout meals. Their most recent dinner, on April 8, raised around $1,400, said Oneita.

Moving out of the church meant not just more of the organizing work they did inside, but also adjusting to the reality of life in a pandemic.

"It didn't feel like the world we left, out there," Oneita said.

Their youngest, Timmy, was 12 when they moved into sanctuary. Now he's 15 and a head taller. Living in a church and attending middle school in a new place was hard, said his parents. He was bullied at his last school.

Then, this year, he had to attend ninth grade virtually, which Timmy said was yet another adjustment.

"It was kind of hard at the beginning, especially since it's my first year in high school, but I'm getting through it," he said.

His family decided to rent a home in Philadelphia, instead of returning full-time to New Jersey, in part to keep him from having to change schools again. They are still paying the mortgage on their New Jersey house, and plan to split their time going forward.

Time pressed on in the church, and their family changed in the process. Their two youngest children, Christine, now 18, and Timmy, moved into sanctuary with them. Christine plans to start nursing school in the fall. Their older son, Clive Jr., started a film degree at Columbia University, and dreams of becoming a famous director. CJ has pulled directly from his family's experience in sanctuary for inspiration for a screenplay.

For him, the recent developments mean "finally being able to move past worrying about my family and how they're doing," CJ said. "A lot of weight [is] taken off my shoulders knowing they're in an actual house now."

Leaving sanctuary also left the Thompsons with a profound appreciation for the good in other people, for the strangers who became supporters, and then friends.

"We are so grateful for them, and even to this day, they're still in our life. They check on us every day, even though we are not in the church," Clive said.

Sitting in their new living room, Clive and Oneita are looking forward, not back, and planning a big celebration for when they finally get their green cards with everyone who came into their lives during sanctuary.

"Once I have money, I'm going to par-tay!," Oneita said with a laugh.

Copyright 2021 WHYY. To see more, visit WHYY.