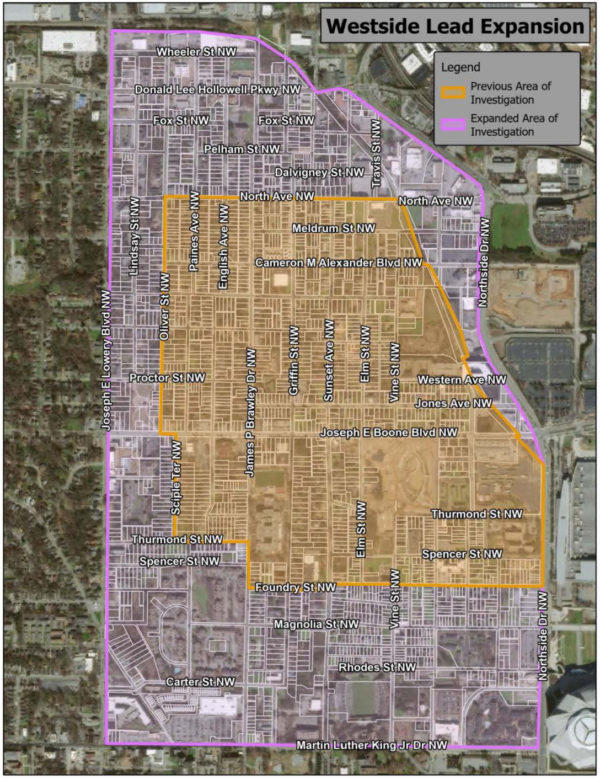

Caption

On a Saturday morning, dozens of volunteers handed out leaflets, telling residents of the English Avenue community about the EPA’s free lead testing of soil, and urging them to get children tested for poisoning.

Credit: Georgia Health News