Section Branding

Header Content

President Biden Wants To Replace All Lead Pipes. Flint Has Lessons To Share

Primary Content

Harold Harrington is a master plumber. Fixing people's pipes is what he does. But it was something he found in his own home in Flint, Mich., that disturbed him.

"This came out of my house," Harrington says as he holds a small piece of pipe. "This piece of galvanized was in my basement. It fed my upstairs faucet and this is out of my upstairs bathroom. ... It's full of lead."

Harrington is among the tens of thousands of residents of Flint whose contaminated drinking water cast a spotlight on a threat faced by communities across the United States.

Flint's lead crisis began in 2014 when the city's drinking water source was switched to save money. Water from the new source was not properly treated, damaging old pipes that leached lead into the drinking water.

Lead can cause damage to the brain and kidneys. Of particular concern is the effect lead can have on young children. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says lead exposure may slow development in kids under 7 years old, leading to learning and behavioral problems.

President Biden has proposed a jobs and infrastructure plan of more than $2 trillion that would set aside billions to replace the nation's lead water pipes. When he announced his American Jobs Plan in April, the president pointed to Flint's troubles as a cautionary tale about the dangers of letting infrastructure decay.

"Everybody remembers what happened in Flint," Biden said. "There's hundreds of Flints all across America."

But Flint is also an example of how to fix the problem — and the many challenges along the way that could slow progress.

Since 2016, the city of Flint has inspected 26,819 service lines and replaced 9,941 lead and galvanized pipes.

Harrington has helped, and it has not been easy. In his union local office, Harrington holds an old lead pipe that's twisted like a pretzel after decades underground.

"You're not just going to dig a hole because those have been there longer than the gas lines, the cable lines, the fiber optic lines. You've got tree roots that have grown in the last hundred years," Harrington says.

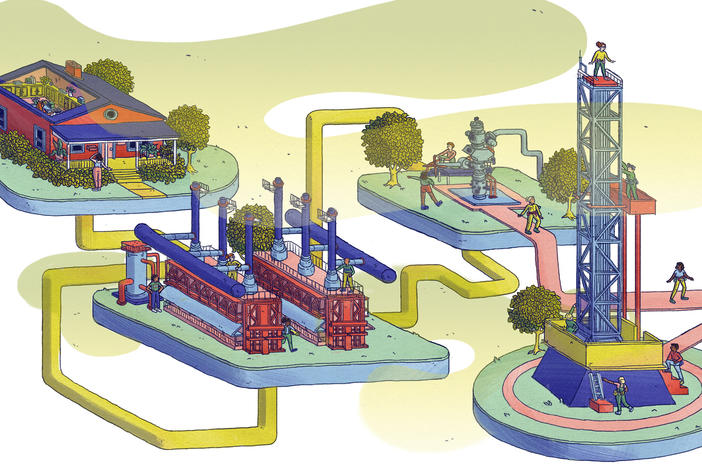

Even determining whether the pipe in the ground is lead, copper or a combination can be tricky. In many cities, old water department records are incomplete or out of date. And for decades, water utilities only replaced pipes to the property line, creating service lines that are a mix of lead, galvanized and copper pipes, which now have to be fully replaced.

"It's a major project," Harrington says, "and every one of them is different."

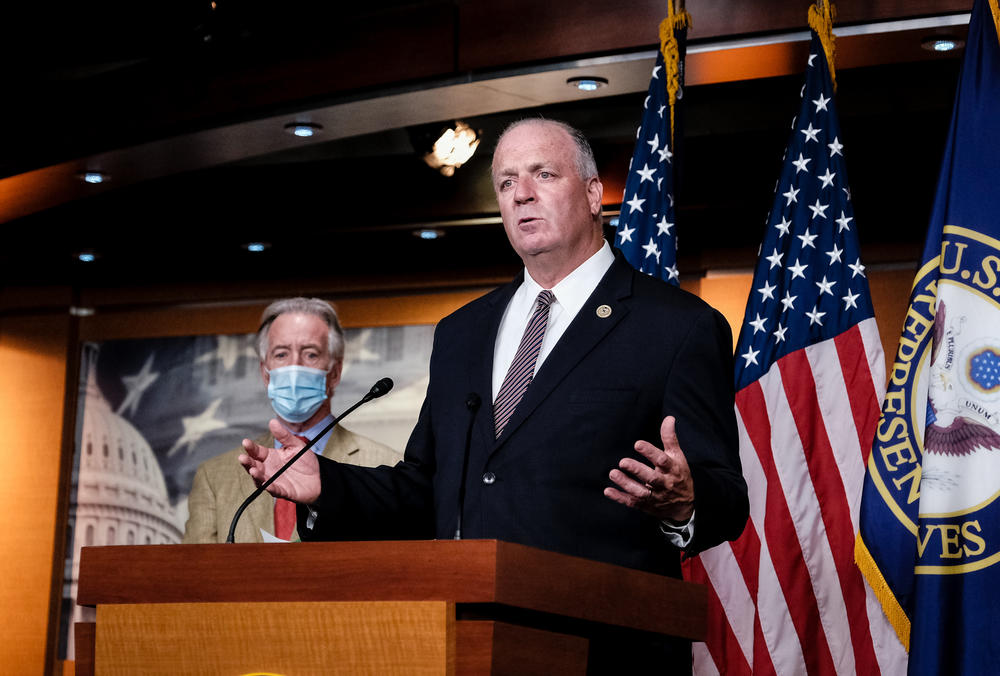

U.S. Rep. Dan Kildee, D-Flint, has spent the past six years channeling federal funds to alleviate lead's long-term effect on his hometown neighbors. He says the crisis could have been averted if the nation had invested more in infrastructure in the past.

"If 10 years ago, $15 or $20 million could have been committed to upgrade the water system in Flint and to get on a path of eliminating lead service lines," he says, "maybe the half a billion dollars that's already been committed could have been avoided."

The Flint water crisis elevated the issue of old lead pipes to the national stage. But public health advocates have been warning for years that the country needed a comprehensive plan to replace lead pipes.

"The Biden plan is way overdue," says Erik Olson, a senior strategic director with the Natural Resources Defense Council. Olson says lead and galvanized pipes continue to be a problem, despite being banned in 1986.

"A lot of people think this is only a problem, say, in Flint or a few big, older cities," Olson says. "But, in fact, it's distributed all over the country and it really is a major public health threat."

Nationwide, the number of lead and galvanized pipes that need to be replaced is estimated between 8 and 10 million. The Biden proposal calls for spending $45 billion, or roughly $5,000 to replace each lead service line.

But the price tag in the end could be much higher. The American Water Works Association, an industry group representing water utilities and manufacturers, pegs the cost at more than $60 billion.

That concerns Allen Overton. He's the pastor of Flint's Christ Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church. Overton joined others who sued to get the city to replace all of its lead service lines. In 2017, a federal judge approved a settlement under which the state of Michigan agreed to spend nearly $100 million to replace all of Flint's lead and galvanized service lines in three years. The pipe replacement program is two years behind schedule but is expected to be completed this year.

As the Biden administration pushes to replicate Flint's pipe replacement experience, Overton worries that more-affluent suburbs would rush in and deplete the proposed federal funding, leaving out disadvantaged communities. He wants money to be earmarked first for communities of color.

"People in brown, Black, African American, Latino communities ... are going to have some disadvantages coming up the ranks," says Overton.

Is replacing pipes the right move?

Some question whether lead service lines should be such a high priority. Lead pipe replacement makes up nearly half of the Biden administration's proposed $110 billion to upgrade the nation's water infrastructure. But by some estimates, the U.S. needs to spend close to $1 trillion to upgrade the entire drinking and waste water system, from water treatment plants to distribution lines.

"A large investment was made in distribution systems after World War II," says David LaFrance, CEO of the American Water Works Association. "Those pipes are all coming of age and they all need to be replaced."

Others point out that water systems can reduce the risk posed by aging pipes without undertaking a vast, complex task of replacing millions of service lines.

"There is an approach to corrosion control which limits and prevents a lot of the leaching of lead," says Michael Shapiro, a former water official with the Environmental Protection Agency. He says it can be done by treating water with anti-corrosion chemicals. But, he says, "Flint showed to an extreme degree, there are limitations to that approach."

Some cities are in no rush

Even with a federal initiative there will likely be those who resist replacing old service lines. And there is even some reluctance in Michigan, which has its own mandate to remove all lead service lines within the next two decades.

The small bedroom community of Mason was founded in south-central Michigan in the mid-1800s. And some of its estimated 1,400 lead service lines date back that far.

On an unusually warm April morning, Mayor Russ Whipple sits in his backyard listening to birds singing. He says Mason has been slowly replacing old pipes during routine roadwork. He bristles at the state mandate and insists there's no need to rush it.

"Our lead almost never reaches the threshold," he says. "When it does, it barely does. And usually we find out that the reason it did was because of a bad test."

Despite his reservations, Whipple says if federal funding becomes available his community will likely apply to avoid passing the costs of pipe replacements on to the small city's water customers.

Just up the road from Mason, in Lansing, the state capital, the city's water utility has already replaced all of its lead service lines. But it took 12 years — and a little arm-twisting.

Dick Peffley is the general manager of the Lansing Board of Water and Light. He says most Lansing residents willingly let utility crews inside their homes and allowed them to excavate their lawns to replace the pipes. But some didn't. To get those reluctant property owners to open their doors, the utility had to use what Peffley describes as "tough love."

"We just finally sent a series of letters saying, 'Listen, we need to get your lead service replaced for your own safety. We might be forced to turn your water off, and we'll turn it on when we put new service in,'" he says. "That letter got their attention."

The city of Flint hopes to soon join the ranks of communities that have replaced all of their lead service lines. Flint Mayor Sheldon Neeley plans to inspect the last 500 service lines this summer. "It's a journey," he says, "and we're completing that journey now."

Copyright 2021 Michigan Radio. To see more, visit Michigan Radio.

Bottom Content