Section Branding

Header Content

Here's The Latest List Of The Nation's Most Endangered Historic Places

Primary Content

An unassuming roadside motel that's a spiritual home to the blues. A crumbling Navajo trading post standing right by Monument Valley, and an old filling station that offered refuge to Black travelers during Jim Crow. Campsites — for crusading civil rights demonstrators in the 1960s — and ones that housed Chinese railway workers a century before.

These are among the most endangered historic sites in the U.S. right now, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Every year, the organization issues a list of buildings and other places threatened by development, climate change or neglect.

"This list draws attention to historic places we must protect and honor — not only because they define our past, but also because the stories they tell offer important lessons for the way forward together," said Paul Edmondson, president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, in a statement.

According to the organization, this list really works. Since the National Trust started spotlighting places 34 years ago, it says less than five percent of these endangered sites have been permanently lost. That's more than three hundred, that include Governors Island in New York City, the National Negro Opera Company House in Pittsburgh, the Cathedral Chapel of St. Vibiana in Los Angeles and Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas.

Here is the roundup of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places, listed alphabetically by state. All information below provided by the National Trust for Historic Preservation:

Selma to Montgomery March Camp Sites, Selma, Alabama

In March 1965, as thousands of Civil Rights demonstrators marched from Selma to Montgomery to campaign for full voting rights, three African American farm owners along the 54-mile route courageously offered their properties as overnight camp sites for the marchers, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King, and Congressman John Lewis. These families are among those who Dr. King called the "ordinary people with extraordinary vision" as they risked their lives in support of the Civil Rights movement. Today, several of these sites — the David Hall Farm and Robert Gardner Farm — are still proudly owned by the same families and are situated along the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, but their incredible stories remain largely untold. Many of the farm properties now need stabilization, repair, and interpretation to expand the narrative of this significant landscape in Civil Rights history and share the stories of these families, whose tremendous bravery helped to change American history.

Summit Tunnels 6 & 7 and Summit Camp Site, Truckee, California

The Summit Tunnels 6 & 7 and Summit Camp Site tell the story of thousands of Chinese railroad workers who constructed the Transcontinental Railroad through the Sierra Nevada mountains from 1865 to 1867. These workers, making up approximately 90 percent of the Central Pacific Railroad workforce, risked their lives to cut and build railroad beds and dig tunnels in incredibly difficult working conditions and extremely dangerous terrain and weather — all while being paid less than their white counterparts. Vandalism currently threatens the tunnels, resulting in extensive graffiti, as well as physical damage to cultural and natural resources at the site. The Tahoe National Forest protects the archaeological remains of Summit Camp, but visitors who don't understand its significance are not always respectful of the site's remaining artifacts. Highlighting how Chinese laborers accelerated the development of the American West, and better interpreting and protecting these sites, would honor this important and often overlooked part of our country's history.

Trujillo Adobe, Riverside, California

Constructed in 1862 by the Trujillo family, and today the oldest known building in Riverside, the Trujillo Adobe tells the story of migration and settlement in inland southern California. Lorenzo Trujillo, who built the Adobe in what was then a part of Mexico, was a Genízaro — one of many Native Americans who were captured, sometimes held in slavery, sometimes baptized and raised by Spanish colonists. Trujillo led many expeditions as a scout across the Old Spanish Trail, enabling immigrants to settle inland California, and his home became the beating heart of a community known as La Placita de los Trujillos, Spanish Town, and Agua Mansa. The Adobe is now deteriorated and fragile, protected only by a wooden structure (also in need of repair) that hides the Adobe from view. Local advocates hope to transform the Adobe into a cultural and educational site to recognize and take pride in the multiple cultures that shaped and continue to define the region.

Georgia B. Williams Nursing Home, Camilla, Georgia

The Georgia B. Williams Nursing Home was the residence of Beatrice Borders, a Black midwife who used the space to serve communities in southwest Georgia during the Jim Crow era. Over several decades, Mrs. Borders and her assistants persevered through local and systemic racism to deliver more than 6,000 babies, and the Nursing Home provided the only known birthing center of its kind for thousands of Black women in the rural South during times of challenging economic and living conditions. The vacant nursing home, now uninhabitable, suffers from water damage and deterioration. Local advocates are leading a campaign to rehabilitate the facility as a museum and educational center where they can share Mrs. Borders' story as well as the stories of the children delivered by "Miss Bea."

Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 Order of Moses Cemetery and Hall, Cabin John, Maryland.

Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 Order of Moses Cemetery and Hall were established around 1885 alongside a post-Emancipation Black settlement known as Gibson Grove. Residents, some of whom had been formerly enslaved, established a local benevolent society to care for the sick and destitute, bury the deceased, and provide overall support to the local Black community. In an act of racial injustice, highway construction in the 1960s ran through the Gibson Grove community and took a portion of the cemetery site. Today, foundations are all that remain of Moses Hall, and the planned expansion of the Washington, D.C.-area Beltway further threatens the cemetery, where known burials span from 1894 to 1977. A coalition of neighbors and descendants is leading the effort to save this place by advocating that new Capital Beltway construction avoid the cemetery and hall site.

Boston Harbor Islands, Boston, Massachusetts

The Boston Harbor Islands, now part of a National and State Park, are home to a wealth of historic resources dating back 12,000 years, including the most intact Native American archaeological landscape remaining in Boston, historic Fort Standish, the Boston Light, and more. Storm surges, which are intensifying due to climate change and sea level rise, are causing accelerated coastal erosion resulting in the escalated loss of archeological sites and other historic resources. Protecting these sites before their stories are lost requires greater public attention, funding for mitigation efforts and archeological studies, and strategies to document and protect historic and natural resources from climate-related storm surges.

Sarah E. Ray House, Detroit, Michigan

Sarah Elizabeth Ray was a Civil Rights activist who filed a successful discrimination case after the SS Columbia, a steamboat that carried passengers to Detroit's Bob-Lo Island Amusement Park, ejected her on the basis of race. Her 1948 case was eventually decided in Ray's favor by the U.S. Supreme Court and was an important precursor to the Brown v. Board of Education decision, which struck down the doctrine of separate but equal educational facilities in 1954. Ray's Civil Rights work in Detroit continued over her lifetime. Following the violent confrontations between Black residents and the city's police department in the summer of 1967 in Detroit, Ray and her husband opened a community center called Action House to stabilize their neighborhood, promote racial tolerance, and enrich the lives of local children. They also bought the house next door for their primary residence, where Ray lived until her death in 2006. While the Action House was eventually demolished, Ray's home remains. It is vacant and deteriorated, but still contains her personal papers, photos, books, and memorabilia. The Sarah Elizabeth Ray Project is leading the effort to save the house, conserve its contents, and elevate the story of this little-known Civil Rights activist.

The Riverside Hotel, Clarksdale, Mississippi

In 1944, Mrs. Z.L. Ratliffe opened The Riverside Hotel as a boarding house for Blacks, eventually extending the building to include 20 guest rooms over two floors. As one of the only Black hotels and boarding homes in Jim Crow-era Mississippi, The Riverside played host to a who's who of musical legends such as Muddy Waters, Sam Cooke, Howlin' Wolf, and Duke Ellington, making it central to American musical history as a landmark of the legendary Delta Blues sound and — literally — one of the birthplaces of rock and roll. Owned by the Ratliffe family since 1957, The Riverside is also the only hotel related to blues history that is still Black-owned in Clarksdale. But the building, which has not been operational since storm damage in April 2020, needs significant rehabilitation. The current owners are seeking partnerships and funding to repair and reopen the hotel so it can continue to serve as a destination for musicians, tour groups, and other blues aficionados.

Threatt Filling Station and Family Farm, Luther, Oklahoma

The entrepreneurial Threatt family first sold produce from their 150-acre family farm outside Luther, Oklahoma, in the early 1900s, and over time expanded their offerings to include a filling station (built in 1915), ballfield, outdoor stage, and bar. The filling station was the only known Black-owned and operated gas station along Route 66 during the Jim Crow era, making it a safe haven for Black travelers. The farm also reportedly provided refuge to Blacks displaced by the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The Threatt family still proudly owns the property and envisions revitalizing this site in time for the 2026 Centennial of Route 66, starting Route 66's second century off with a more representative narrative of the legendary "Mother Road." But they need partners and financial support to fully restore the filling station and bar and do justice to its stories of Black entrepreneurship and travel.

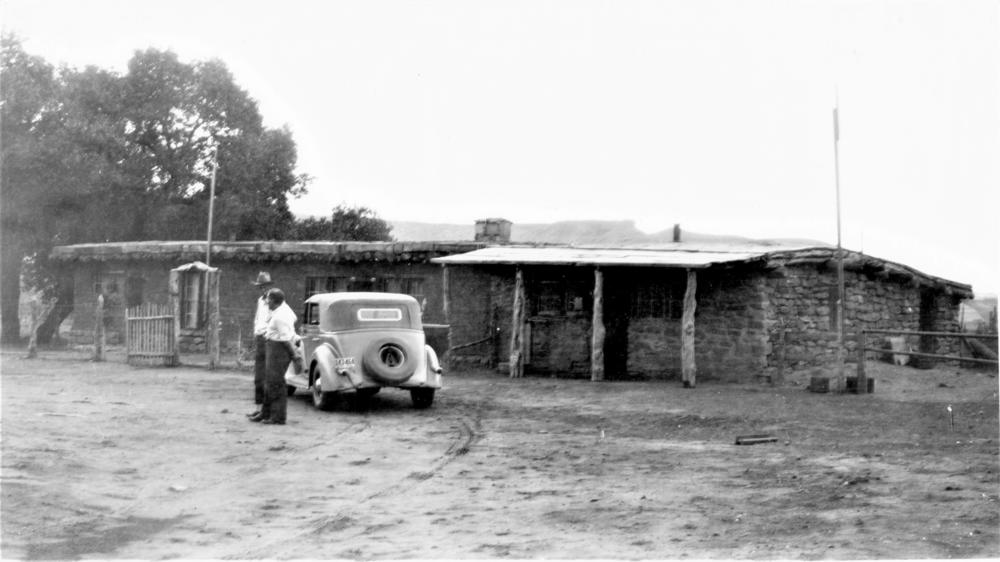

Oljato Trading Post, San Juan County, Utah

The Oljato Trading Post is a rare example of a once-ubiquitous mainstay in Navajo communities — trading posts that offered a wide assortment of goods, provided Navajo producers a place to sell or trade their products, and acted as community centers and social hubs. Built in 1921 by a licensed Anglo trader, the National Register-listed Oljato complex includes a trading room, living area, storage for wares, and a traditional hogan (or sacred home) for overnighters. The trading post is now entirely in Oljato and Navajo hands, providing an opportunity to adapt the trading post in a way that brings more resources, attention, economic opportunity, and social benefits to the tribal communities. However, the deteriorated facility needs $1.3 million for rehabilitation so it can have a new life as a community center and cultural tourist destination.

Pine Grove Elementary School, Cumberland, Virginia

Built in 1917 as a Rosenwald School, the two-room Pine Grove Elementary School served its African American agricultural community as a center for education, programs, and Civil Rights activities during the era of segregation. After it closed in 1964, the building was saved twice by Black community leaders, alumni, and descendants of alumni. However, the proposed construction of a nearby landfill now threatens the Pine Grove Elementary School. According to the Green Ridge Recycling and Disposal Facility, the landfill intends to accept up to 5,000 tons of waste daily and operate 24 hours a day, six days per week. Moreover, the disposal unit will be located within one thousand feet of Pine Grove Elementary School. Advocates believe that the proposed landfill could negatively impact their goal of using the school as a community center.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.