Section Branding

Header Content

Antisemitism Spikes, And Many Jews Wonder: Where Are Our Allies?

Primary Content

For Alex Zeldin, it began as a normal Friday.

He was headed to Trader Joe's on New York City's Upper West Side to pick up some food for the Jewish Sabbath.

As usual, he was wearing his yarmulke, or skullcap. When he turned a corner, he realized that a couple of teenagers had started to follow him, spewing antisemitic insults.

"It took me about halfway down the block to realize that the thing that they were commenting on was they kept saying, 'Yarmulke': 'I want to take that yarmulke. I want to hit him in his head and take that yarmulke. That Jewish baby killer,' " Zeldin recalled.

Zeldin's harassers ultimately peeled off, but the fact that they used the term "baby killer" gave him a jolt.

"Calling Jews 'baby killers'? That's the blood libel. That's a thing that was happening in medieval Europe," he said, referring to the age-old, antisemitic lie that accused Jews of murdering Christian children to use their blood in rituals.

Zeldin, who writes a column for The Forward, a Jewish publication devoted to news and progressive thought, notes that "baby killer" invective has gained traction — propagated widely on social media — in response to last month's military conflict between Israel and Hamas, which left dozens of Palestinian children among the dead.

During nearly two weeks of fighting, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) tracked a 75% spike in antisemitic incidents in the U.S., including brazen assaults, vandalism, harassment and hate speech.

"It was like a wildfire that spread much farther than we had anticipated or really seen in the past," said Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO and national director of the ADL. "We were pretty staggered to see how fast this played out."

That antisemitic surge is an alarming trend, one that has also left many Jews wondering where their allies have gone.

"Who is here for us?"

Zeldin has heard from many Jews who feel they've been abandoned by people whom they would expect to be their allies.

"It's definitely a moment of frustration," he said. "A lot of the messaging that Jews have gotten over the last four years ... is you've got to show up. You have to be an ally. You have to speak up for others. And I think a lot of Jews, myself included, very much took that to heart," marching in support of women's and immigrant rights, as well as the Black Lives Matter movement.

But recently, he said, reciprocity has been hard to find.

"I don't think that the general population, and progressives included among that, have a good understanding of what they're looking at when antisemitic violence doesn't have a swastika attached to it," Zeldin said.

He said people find it easier to see and condemn antisemitism when it involves white supremacists chanting, "Jews will not replace us," as they did in the August 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va. Or when a gunman opened fire in a synagogue in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27, 2018, and killed 11 worshippers because he believed a conspiracy theory that claims Jews are helping immigrants resettle in America in order to make the country less white.

But, Zeldin said, when anti-Jewish hate is less glaring or gets twisted up with Middle East geopolitics, "folks struggle to identify it and to understand that it is a severe problem."

Even before the latest flare-up of Mideast violence, some Jews were already feeling abandoned in the fight against antisemitism. Comedian Sarah Silverman talked about it on her podcast in March.

"Stop rolling your eyes, and be our allies," she urged. "It makes me sad to know that so many Jews that I know commit their lives to being allies to so many, to stick their necks out for others, and I'm proud of that. That will always be our way."

"But," she asked, "who is here for us?"

Justice, justice you shall pursue

Rabbi Sandra Lawson approaches that question — "who is here for us?" — from multiple perspectives. As a Black, queer, female rabbi, Lawson is at the intersection of marginalized identities.

"People's allyship should not be conditional," she said. "It should not be 'I showed up for you, or these groups — therefore you show up for me.' You should do it because it's the right thing to do."

And it requires building real relationships, Lawson said.

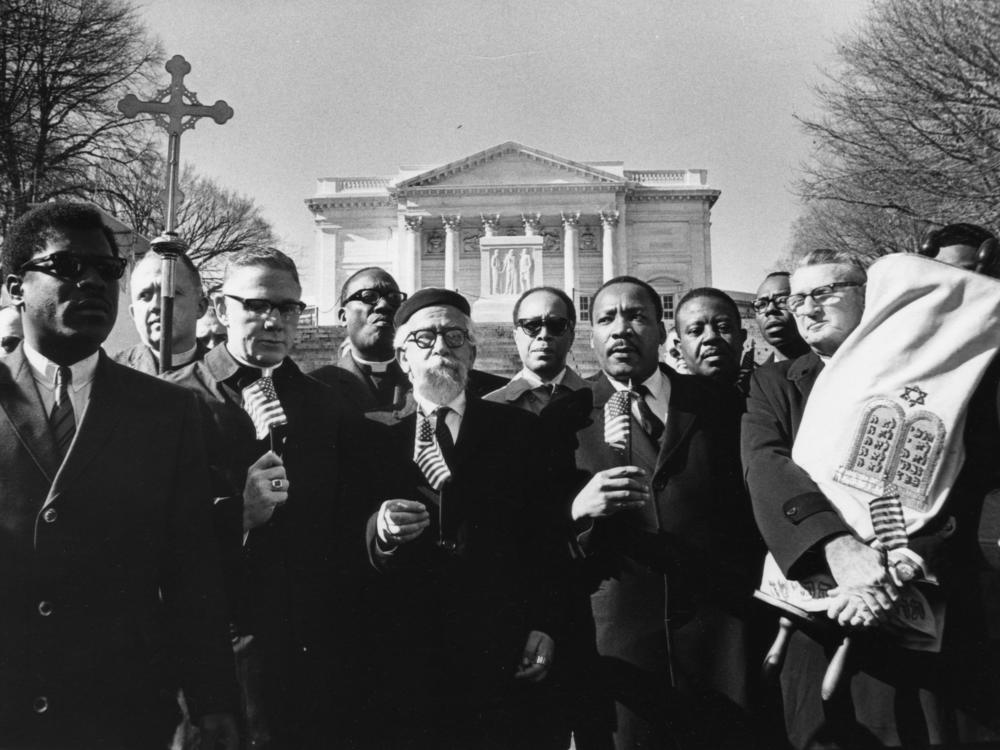

Reflecting on the Jewish theologian Rabbi Abraham Heschel's storied alliance with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the civil rights movement, Lawson pointed out that "what gets left out of the story is that they were actual friends. And so if you want to show up for Black Lives Matter, that's fine, that's outwardly facing. But the hard work is the internal work that you have to do in yourself to understand racism, antisemitism, homophobia. ... And that's the work that people don't want to do."

Lawson is director of diversity, equity and inclusion with the progressive Jewish organization Reconstructing Judaism, and she joined our Zoom call wearing a T-shirt with the message "Justice, justice you shall pursue."

"It's from the Torah," Lawson explained; transliterated from Hebrew, it's tzedek tzedek tirdof.

"The fact that justice — tzedek tzedek — is said twice, it sort of becomes an imperative," she said. "You must do this. You must pursue justice." Below that phrase, her shirt read: "Jewish and anti-racist."

Lawson is an active presence on social media and lately has found herself the target of escalating vitriol, even in response to the most benign things, like a TikTok video she posted where she's napping with her tiny dog.

This was right after the Israeli military launched airstrikes in Gaza, following a barrage of rockets launched into Israel by Palestinian militants.

"It just didn't feel like one individual throwing antisemitic statements at me," Lawson said. "It was like one after another after another after another. I had people say things like: 'Jews were responsible for the slave trade.' 'How can [you] support Israel?' 'Hitler was right.' "

According to the Anti-Defamation League, variations of the phrase "Hitler was right" were tweeted more than 17,000 times in the first week of the fighting between Israel and Hamas.

Responding to the surge in anti-Jewish hate and physical assaults, President Biden issued a statement on May 28 saying, "These attacks are despicable, unconscionable, un-American, and they must stop. I will not allow our fellow Americans to be intimidated or attacked because of who they are or the faith they practice."

While the ADL's Greenblatt praised the president's long-standing commitment on this issue, he was dismayed that high-profile public condemnation had been slow in coming.

"It took too long," he said, "and too much happened before we had leaders speak out. ... We would hope to see, whether you're a college president, you're a chief executive, to stand up squarely and unapologetically for a besieged Jewish community, just like they do for other marginalized groups."

A hierarchy of racism

So, what explains the reluctance?

The British writer and comedian David Baddiel, who is Jewish, offers an answer in a recently published book titled Jews Don't Count. It's aimed specifically at the progressive left.

"I think progressives find it very hard to see Jews as victims," Baddiel said in an interview.

He attributes this aversion to the myth that Jews are rich, powerful and privileged — an antisemitic trope in itself that has also come down through history.

"And the problem is that if you have any trace of that in your consciousness," he said, "and trust me, a lot of people on the left do, then it's hard to think of Jews as being inside that circle of people you need to protect, because the Jews are not in need of protection."

Or, as he put it in his book, Jews find themselves pushed outside of the "sacred circle" that the "progressive modern left [is] prepared to go into battle for."

The key, Baddiel argues, is that antisemitism has to be understood as racism. It has very little to do with religion.

"Because no racist asks whether you keep kosher before they set light to your house," he said. "I am an atheist. It would not have given me a free pass out of Auschwitz. It would also be irrelevant to any white supremacist wanting to kill me."

Baddiel speaks with the weight of family history behind him: His grandparents fled the Nazis with his mother when she was an infant, and many other family members were murdered in the Holocaust.

In Jews Don't Count, he writes, "The sense, perhaps, is that Jews don't need allies."

But, he concludes, "That isn't true: it never was."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.