Section Branding

Header Content

Carbon Dioxide, Which Drives Climate Change, Reaches Highest Level In 4 Million Years

Primary Content

The amount of carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere reached 419 parts per million in May, its highest level in more than four million years, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced on Monday.

After dipping last year because of pandemic-fueled lockdowns, emissions of greenhouse gases have begun to soar again as economies open and people resume work and travel. The newly released data about May carbon dioxide levels show that the global community so far has failed to slow the accumulation of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, NOAA said in its announcement.

"We are adding roughly 40 billion metric tons of CO2 pollution to the atmosphere per year," said Pieter Tans, a senior scientist with NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory, in a statement. "If we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, the highest priority must be to reduce CO2 pollution to zero at the earliest possible date."

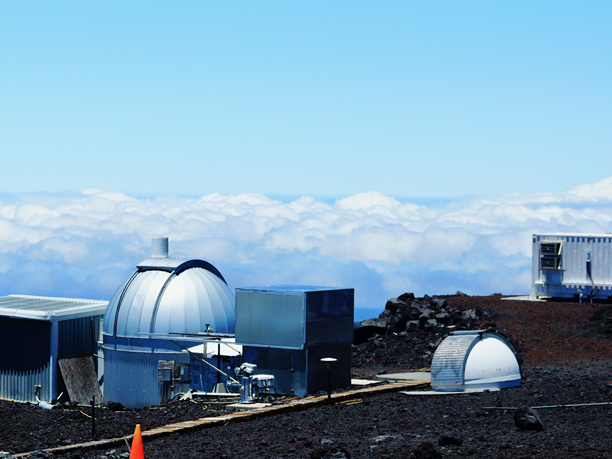

The May measurement is the monthly average of atmospheric data recorded by NOAA and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at an observatory atop Hawaii's Mauna Loa volcano. NOAA's monthly average from its measurements came to 419.13 parts per million, and scientists from Scripps calculated their average as 418.92. A year ago, the average was 417 parts per million.

The last time the atmosphere held similar amounts of carbon dioxide was during the Pliocene period, NOAA said, about 4.1 to 4.5 million years ago. At that time, sea levels were 78 feet higher. The planet was an average of 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer, and large forests might have grown in what is today's Arctic tundra.

Homo erectus, an early human ancestor, emerged about two million years ago on a much cooler planet. At the time, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels averaged about 230 parts per million — a bit over half of today's levels.

Since 1958, scientists with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, and later, NOAA, have regularly measured the amount of carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere at a weather station atop Mauna Loa. Each year, concentrations of carbon dioxide increase enough to set a new record.

"We still have a long way to go to halt the rise, as each year more CO2 piles up in the atmosphere," said Scripps geochemist Ralph Keeling. "We ultimately need cuts that are much larger and sustained longer than the COVID-related shutdowns of 2020."

Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that remains in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. The last century of steep increases in carbon dioxide is driven almost entirely by human activity, mainly the burning of fossil fuels. The effects of climate change are already being felt, as bigger and more intense hurricanes, flooding, heatwaves and wildfire routinely batter communities all over the world.

To avoid even more dire scenarios in the future, countries must sharply cut their emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, scientists say.

The United States formally rejoined the Paris Agreement on climate change in February. Around the same time, the United Nations warned that the emission reduction goals of the 196 member countries are deeply insufficient to meet the agreement's target of limiting global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. Temperatures have already risen about 1 degree Celsius since the mid-1800s, when the use of fossil fuels became widespread.

NOAA scientist Tans suggested, though, that society has the tools it needs to stop emitting carbon dioxide.

"Solar energy and wind are already cheaper than fossil fuels and they work at the scales that are required," said Tans. "If we take real action soon, we might still be able to avoid catastrophic climate change."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.