Caption

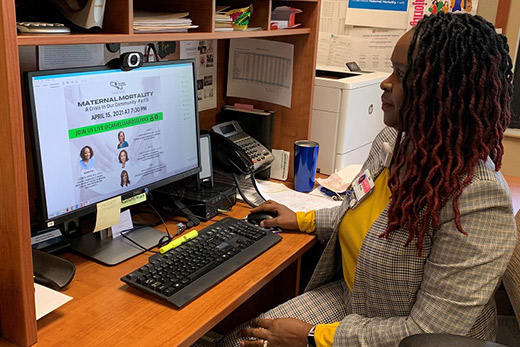

Rose L. Horton, executive director of Women and Infant Services at Emory Decatur Hospital, will help guide the Biden adminstration’s efforts to combat maternal mortality in the Black community as part of a new national stakeholder group.

Credit: Emory University