Caption

Jo Ann Gibson, born in Culloden and raised in Macon, was instrumental in organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott that helped spark the Civil Rights Movement.

Credit: Courtesy Montgomery County Archives

|Updated: June 17, 2021 9:49 AM

Jo Ann Gibson, born in Culloden and raised in Macon, was instrumental in organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott that helped spark the Civil Rights Movement.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to move from the front of a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

The following Monday, the first largely successful demonstration to integrate buses across the South began. A Middle Georgia native had been planning the Montgomery Bus Boycott for more than three years, the success of which helped propel the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to prominence.

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, of Culloden, was the president of the Women’s Political Council, which planned the first day of the boycott.

“I think that people were fed up,” Robinson said during an interview for “America, They Loved You Madly” in 1979. "They had reached the point that they knew there was no return — that they had to do it or die. And that’s what kept it going. It was the sheer spirit for freedom, for the feeling of being a man and a woman."

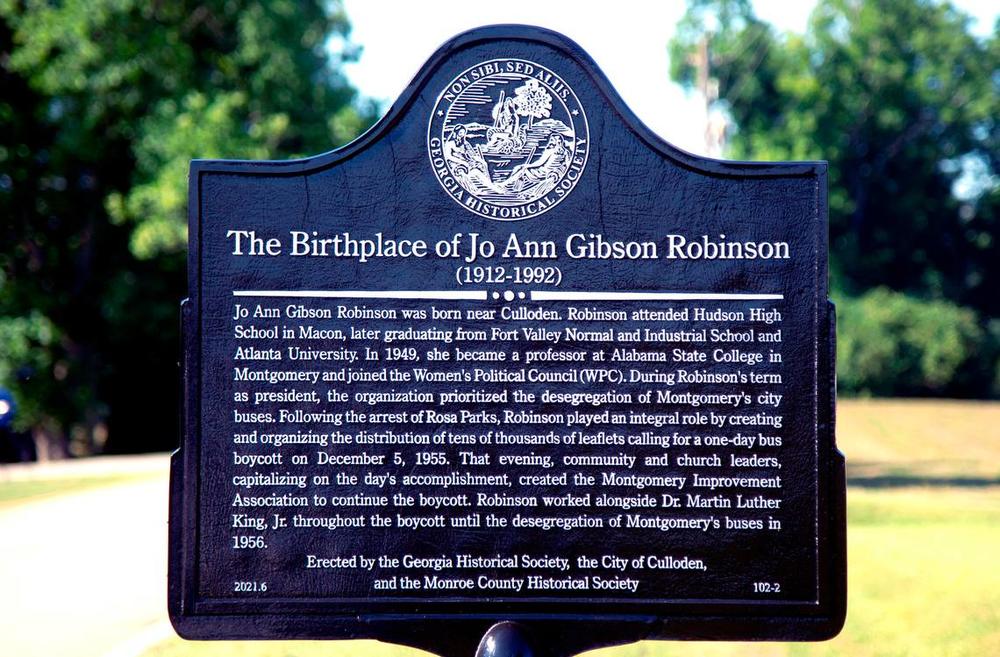

Robinson and her family were honored in Culloden on Wednesday with a historical marker near 3 Old Highway 341 detailing Robinson’s role in the Civil Rights Movement.

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson was honored in Culloden on Wednesday with a historical marker near 3 Old Highway 341 detailing Robinson’s role in the Civil Rights Movement.

Mark Smith, a history teacher at Mary Persons High School who submitted the proposal for the historical marker, said he learned about Robinson in college and was shocked he’d never heard of her.

“I was like, ‘Wow!’ My whole life I’ve never heard of her and not that many people have,” he said. “She did all this amazing work, but yet, she’s kind of forgotten. Rosa Parks and Dr. King you remember from the movement, but not the lady who kick-started the whole thing, and so I said ‘That needs to change.’”

Robinson was born in Culloden, a small town in Monroe County, on April 17, 1912, and she was the 12th and last child to Owen and Dollie Webb Gibson.

After her father died when she was 6, her family moved to Macon, Smith said.

She graduated from Ballard-Hudson High School as the valedictorian and pursued a degree in education at Fort Valley State College (now Fort Valley State University), where she graduated in 1934. She taught at Ballard-Hudson before attending what is now Clark Atlanta University to receive a master’s degree.

After receiving her education, she headed to Alabama State College in Montgomery in 1949.

She died in Los Angeles in 1992.

Smith said Robinson experienced a traumatic event while boarding a bus to Ohio to see family during the Christmas holiday.

After sitting down, tired and ready to start her journey, she realized the bus was not moving and the bus driver was yelling at her.

“The bus driver’s yelling at her to move to the segregated section, and so she’s just frightened with terror and just stays there and the bus driver comes up and yells at her and she just stumbles off the bus, embarrassed and ashamed; and from that point forward she made the integration of buses a personal priority of hers,” Smith said.

She became the president of the Women’s Political Council in 1950, and more than a year before the boycott she wrote a letter to the mayor of Montgomery asking for the desegregation of buses.

Although the boycott is known to have started right after Rosa Parks was arrested, Robinson said in the 1979 interview that the Women’s Political Council in Montgomery had been planning it for years.

After Parks was arrested, Robinson had tens of thousands of leaflets printed to let people know the boycott would start Dec. 5; she had her students at Alabama State College distribute them.

“She organized the distribution of it,” Smith said. "She came up with the leaflet and she basically kicked the whole thing off, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott was the first massively successful resistance in the South."

That Monday night, boycott organizers had a meeting to vote on whether to continue the bus boycott, and Robinson said after the first day, the plan was for the pastors to take over the boycott.

“The people wanted to continue that boycott,” Robinson said in the interview. "They had been touched by the persecution, the humiliation that many of them had endured on buses, and they voted for it unanimously."

During the 13 months of the boycott, Robinson had her car windows broken and watched police pour acid on her car.

“Well, I never reached a point where I was sorry,” she said. "I reached a point where I was scared."

The boycott ended with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that forced Montgomery to integrate the buses and King emerged as the leader of the Civil Rights Movement.

Oscar Webb, Robinson’s cousin, credits Robinson with helping King and other Civil Rights leaders rise to prominence.

“I wanted the world to know what she did, and her legacy because it wasn’t so much about a bus… but it’s about people coming together; because if it was not for her, you wouldn’t have had Dr. King,” he said. “Her legacy is to be the woman who helped propel Dr. Martin Luther King to promise.”

Robinson said in the interview that they held a meeting after the verdict to celebrate their victory.

“We had won self-respect… We felt that we were somebody, that somebody had to listen to us, that we had forced the white man to give what we knew was a part of our own citizenship,” she said. “If you have never had the feeling that this is not the other man’s country, and you are an alien in it, but that this is your country, too, then you don’t know what I’m talking about.

“But it is a hilarious feeling that just goes all over you, that makes you feel that America is a great country, and we’re going to do more to make it greater.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Telegraph.