Caption

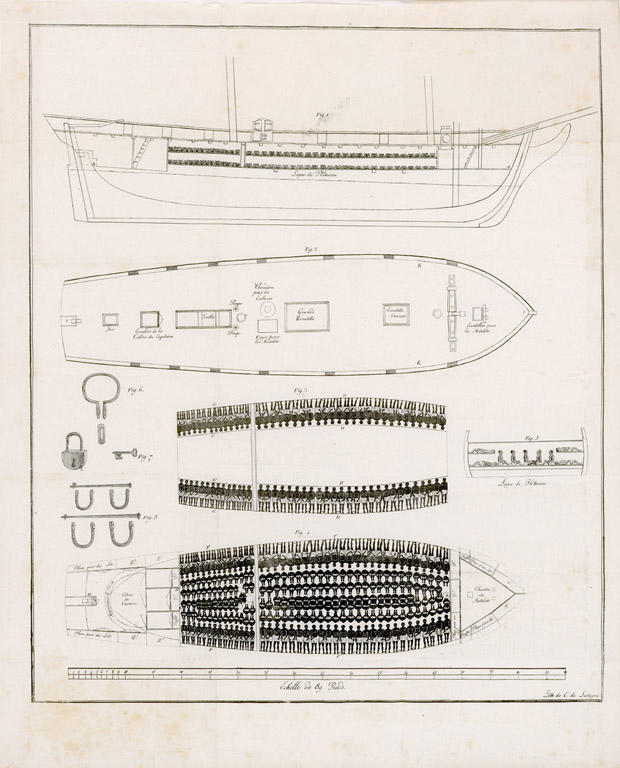

An image, dated from the year 1822, of a slave holding ship that departed from France and carried 345 slaves. This was one of the many ships intercepted by anti-slave trade cruisers before it reached the Americas. The Africans were taken to Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Credit: (Image Courtesy of SlaveVoyages.com and Brown University)