Section Branding

Header Content

A Disturbing Number Of Hospital Workers Still Unvaccinated

Primary Content

Brenda Goodman is a senior news writer for WebMD. Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News. This is the first of a series.

Tim Oswalt had been in a Fort Worth, Texas, hospital for over a month, receiving treatment for a grapefruit-sized tumor in his chest that was pressing on his heart and lungs. It turned out to be stage 3 non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Then one day in January, he was suddenly moved from his semi-private room to an isolated one with special ventilation. The staff explained he had been infected by the virus that was once again surging in many areas of the country, including Texas.

“How the hell did I catch COVID?’” he asked the staff, who now approached him in full moon-suit personal protective equipment (PPE).

The hospital was locked down, and Oswalt hadn’t had any visitors in weeks. Neither of his two roommates tested positive. He’d been tested for COVID several times over the course of his nearly 5-week stay and was always negative.

“Well, you know, it’s easy to [catch it] in a hospital,” Oswalt said he was told. “We’re having a bad outbreak. So you were just exposed somehow.’”

Officials at John Peter Smith (JPS) Hospital, where Oswalt was treated, said they are puzzled by his case. According to their infection prevention team, none of his caregivers tested positive for COVID-19, nor did Oswalt share space with any other COVID positive patients. And yet, local media reported a surge in cases among JPS hospital staff in December.

“Infection of any kind is a constant battle within hospitals, and one that we all take seriously,” said Rob Stephenson, MD, chief quality officer at JPS Health Network. “Anyone in a vulnerable health condition at the height of the pandemic would have been at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 inside — or even more so, outside — the hospital.”

Oswalt was diagnosed with COVID in early January. JPS Hospital began vaccinating its health care workers about 2 weeks earlier, so there had not yet been enough time for any of them to develop full protection against catching or spreading the virus.

Today, the hospital said 74% of its staff — 5,300 of 7,200 workers–are now vaccinated.

Oswalt’s case illustrates the threat of healthcare-acquired COVID — a danger that lurks in American hospitals, where significant numbers of health care workers are still not vaccinated against the SARS-CoV2 virus.

Refusing vaccinations

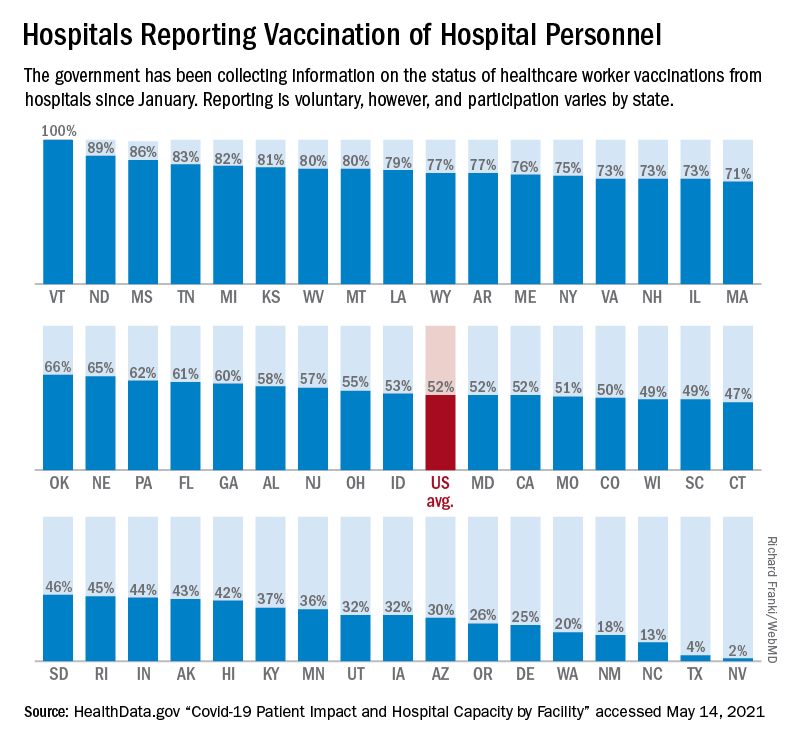

In fact, nationwide, 1 in 4 hospital workers who have direct contact with patients had not yet received a single dose of a COVID vaccine by the end of May, according to a WebMD and Medscape Medical News analysis of data collected by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from 2,500 hospitals across the U.S.

Among the nation’s 50 largest hospitals reviewed, the percentage of unvaccinated health care workers appears to be even larger, about 1 in 3. Vaccination rates range from a high of 99% at Houston Methodist Hospital, which was the first in the nation to mandate the shots for its workers, to a low between 30% and 40% at some hospitals in Florida.

Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center, in Houston, has 1,180 beds and sits less than half a mile from Houston Methodist Hospital. But in terms of worker vaccinations, it is farther away.

Memorial Hermann reported to HHS this month that about 32% of its 28,000 workers haven’t been inoculated. The hospital’s PR office contests that figure, putting it closer to 25% unvaccinated across their health system. The hospital said it is boosting participation by offering a $300 “shot of hope” bonus to workers who start their vaccination series by the end of June.

Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla., reported to HHS that 63% of its health care personnel are still unvaccinated. The hospital did not return a call to verify that number.

To boost vaccination rates, more hospitals are starting to require the shots, after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission gave its green light to mandates in May.

“It’s a real problem that you have such high levels of unvaccinated individuals in hospitals,” said Lawrence Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

“We have to protect our health work force, and we have to protect our patients. Hospitals should be the safest places in the country, and the only way to make them safe is to have a fully vaccinated work force,” Gostin said.

Data misleading

The HHS system designed to amass hospital data was set up quickly, to respond to an emergency. For that reason, experts say the information hasn’t been as carefully collected or vetted as it normally would have been. Some hospitals may have misunderstood how to report their vaccination numbers.

In addition, reporting data on worker vaccinations is voluntary. Only about half of hospitals have chosen to share their numbers. In other cases, like Texas, states have blocked the public release of these statistics.

AdventHealth Orlando, a 1,300-bed hospital in Florida, reported to HHS that 56% of its staff have not started their shots. But spokesman Jeff Grainger said the figures probably overstate the number of unvaccinated workers because the hospital doesn’t always know when people get vaccinated outside of its campus, at a local pharmacy, for example.

For those reasons, the picture of health care worker vaccinations across the country is incomplete.

Where hospitals fall behind

Even if the data are flawed, the vaccination rates from hospitals mirror the general population. A May Gallup poll, for example, found 24% of Americans said they definitely won’t get the vaccine. Another 12% say they plan to get it, but are waiting.

They also align with recent studies. A review of 35 studies by researchers at New Mexico State University that assessed hesitancy in more than 76,000 health care workers around the world found about 23% of them were reluctant to get the shots..

An ongoing monthly survey of more than 1.9 million U.S. Facebook users led by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh recently looked at vaccine hesitancy by occupation. It revealed a spectrum of hesitancy among health care workers corresponding to income and education, ranging from a low of 9% among pharmacists to highs of between 20% and 23% among nursing aides and emergency medical technicians. About 12% of registered nurses and doctors admitted to being hesitant to get a shot.

“Health care workers are not monolithic,” said study author Jagdish Khubchandani, professor of public health sciences at New Mexico State University.

“There’s a big divide between males, doctoral degree holders, older people and the younger low-income, low-education frontline, female, health care workers. They are the most hesitant,” he said. Support staff typically outnumbers doctors at hospitals about 3 to 1.

“There is outreach work to be done there,” said Robin Mejia, Ph.D., director of the Statistics and Human Rights Program at Carnegie Mellon University, who is leading the study on Facebook’s survey data. “These are also high-contact professions. These are people who are seeing patients on a regular basis.”

That’s why, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was planning the national vaccine rollout, they prioritized health care workers for the initially scarce first doses. The intent was to protect vulnerable workers and their patients who are at high risk of infection. But the CDC had another reason for putting health care workers first: After they were safely vaccinated, the hope was that they would encourage wary patients to do the same.

Hospitals were supposed to be hubs of education to help build trust within less confident communities. But not all hospitals have risen to that challenge.

Political affiliation seems to be one contributing factor in vaccine hesitancy. Take, for example, Gordon County, where residents voted for Donald Trump over Joe Biden by a 67-point margin in the 2020 general election. Studies have found that Republicans are more likely to decline vaccines than Democrats.

People who live in rural areas are less likely to be vaccinated than those who live in cities, and that’s true in Gordon County, too. Vaccinations are lagging in this northwest corner of Georgia where factory jobs in chicken processing plants and carpet manufacturing energize the local economy. Just 24% of Gordon County residents are fully vaccinated, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

At AdventHealth Gordon, a 112-bed hospital in Calhoun, just 35% of the 1,723 workers who serve the hospital are at least partially vaccinated, according to data reported to HHS.

'I am not vaccinated'

One reason some hospital staff say they are resisting COVID vaccination is because it’s so new and not yet fully approved by the FDA.

“I am not vaccinated,” said a social services worker for AdventHealth Gordon who asked that her name not be used because she was unauthorized to speak to Medscape Medical News and Georgia Health News. “I just have not felt the need to do that at this time.”

The woman said she doesn’t have a problem with vaccines. She gets the flu shot every year. “I’ve been vaccinated all my life,” she said. But she doesn’t view COVID vaccination in the same way.

“I want to see more testing done,” she said. “It took a long time to get a flu vaccine, and we made a COVID vaccine in 6 months. I want to know, before I start putting something into my body, that the testing is done.”

Staff at her hospital were given the option to be vaccinated or wear a mask. She chose the mask.

Many of her co-workers share her feelings, she said.

Mask expert Linsey Marr, Ph.D., a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech, said N95 masks and vaccines are both highly effective, but the protection from the vaccine is superior because it is continuous.

“It’s hard to wear an N95 at all times. You have to take it off to eat, for example, in a break room in a hospital. I should point out that you can be exposed to the virus in other buildings besides a hospital–restaurants, stores, people’s homes–and because someone can be infected without symptoms, you could easily be around an infected person without knowing it,” she said.

Eventually, staff at AdventHealth Gordon may get a stronger nudge to get the shots. Chief Medical Officer Joseph Joyave, MD, said AdventHealth asks workers to get flu vaccines, or provide them with a reason why they won’t. He expects a similar policy will be adopted for COVID vaccines once they are fully licensed by the FDA.

In the meantime, he does not believe that the hospital is putting patients at risk with its low vaccination rate. “We continue to use PPE, masking in all clinical areas, and continue to screen daily all employees and visitors,” he said.

AdventHealth, the 12th largest hospital system in the nation with 49 hospitals, has at least 20 hospitals with vaccination rates lower than 50%, according to HHS data.

Other hospital systems have approached hesitation around the COVID vaccines differently.

When infectious disease experts at Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville, Tenn., realized early on that many of their workers felt unsure about the vaccines, they set out to move the needle.

“There was a lot of hesitancy and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious disease at Vanderbilt. So the infectious disease division put together a multifaceted program including Q&As, educational sessions, and one-on-one visits with employees, “from the custodians all the way up to the C-Suite,” he said.

Today, HHS data show the hospital is 83% vaccinated. Schaffner thinks the true number is probably higher, about 90%. “We’re very pleased with that,” he said.

In his experience with flu vaccinations, it was extremely difficult in the first year to get workers to take flu shots. The second year it was easier. By the third year it was humdrum, he said, because it had become a cultural norm.

Schaffner expects winning people over to the COVID vaccines will follow a similar course, but “we’re not there yet,” he said.

Protecting patients

There is no question that health care workers carried a heavy load through the worst months of the pandemic. Many of them worked to the point of exhaustion and burnout. Some were the only conduits between isolated patients and their families, holding hands and mobile phones so distanced loved ones could video chat. Many were left inadequately protected because of shortages of masks, gowns, gloves and other gear.

An investigation by Kaiser Health News and The Guardian recently revealed that more than 3,600 health care workers died in COVID’s first year in the U.S. Medscape has curated a continually updated list to honor the fallen health care workers.

Vaccination of health care workers is important to protect these front-line workers and their families who will continue to be at risk of coming into contact with the infection, even as the number of cases falls.

Hesitancy in health care is also dangerous because these clinicians and allied health workers–who may not show any symptoms—can also carry the virus to someone who wouldn’t survive an infection—including patients with organ transplants, those with autoimmune diseases, premature infants, and the elderly.

It is not known how often patients in the U.S. are infected with COVID in health care settings, but case reports reveal that hospitals are still experiencing outbreaks.

On June 1, Northern Lights A.R. Gould Hospital, in Presque Isle, Maine, announced a COVID outbreak on its medical-surgical unit. As of June 22, 13 residents and staff have caught the virus, according to the Maine Centers for Disease Control, which is investigating. Four of the first 5 staff members to test positive had not been fully vaccinated.

According to HHS data, about 20% of the health care workers at that hospital are still unvaccinated.

Oregon Health & Science University Hospital experienced a COVID outbreak connected to its cardiovascular care unit from April to mid-May of this year. According to hospital spokesperson Tracy Brawley, a patient visitor brought the infection to campus, where it ultimately spread to 14 others including “patients, visitors, employees, and learners.”

In a written statement, the hospital said “nearly all” health care workers who tested positive were previously vaccinated and experienced no symptoms or only minor ones. The hospital said it hasn’t identified any onward transmission from health care workers to patients, and also said “It is not yet understood how transmission may have occurred between patients, visitors and health care workers.”

In March, an unvaccinated health care worker in Kentucky carried a SARS-CoV2 variant back to the nursing home where they worked. Some 90% of the residents were fully vaccinated. Ultimately, 26 patients were infected; 18 of them were fully vaccinated. And 20 health care workers, four of whom were vaccinated, were infected.

Vaccines slowed the virus down and made infections less severe, but in this fragile population, they couldn’t stop it completely. One resident, who had survived a bout of COVID almost a year earlier, died. According to the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47% of the workers in that facility were unvaccinated.

In the United Kingdom, statistics collected through that country’s National Health Service also suggest a heavy toll. More than 32,300 patients caught COVID in English hospitals since March 2020. Up to 8700 of them died, according to a recent analysis by The Guardian. The U.K. government recently made COVID vaccinations mandatory for health care workers.

COVID delays cancer care

When cancer patient Tim Oswalt contracted COVID-19, the virus took down his kidneys first. Toxins were building up in his blood, so doctors prescribed dialysis to support his body and buy his kidneys time to heal.

He was in one of these dialysis treatments when his lungs began to quit on him.

“Look, I can’t breathe,” he told the nurse who was supervising his treatment. The nurse gestured to an oxygen tank already hanging by his side, and said, “You should be OK.”

But he wasn’t.

“I can’t breathe,” Oswalt said again. Then the air hunger hit. Oswalt began gasping and couldn’t stop. Today, his voice breaks when he describes this moment. “A lot of it becomes a blur.”

When Oswalt, now 61, regained consciousness, he was hooked up to a ventilator to ease his breathing.

For days, Oswalt clung to the edge of life. His wife, Molly, who wasn’t allowed to see him in the hospital, got a call that he might not make it through the night. She made frantic phone calls to her brother and sister and prayed.

Oswalt was on a ventilator for about a week. His kidneys and lungs healed enough so that he could restart his chemotherapy. He was eventually discharged home on Jan. 22.

The last time he was scanned, the large tumor in his chest had shrunk from the size of a grapefruit to the size of a dime.

But having COVID on top of cancer has had a devastating effect on his life. Before he got sick, Molly said, he couldn’t stay still. He was busy all the time. After spending months in the hospital, his energy was depleted. He couldn’t keep his swimming pool installation business going.

He and Molly had to give up their house in Fort Worth and move in with family in Amarillo. He has had to pause his cancer treatments while doctors wait for his kidneys to heal. Relatives have been raising money on Go Fund Me to pay their bills.

Months after moving across the state to Amarillo and hoping for better days, Tim said he got good news recently: He no longer needs dialysis. A new round of tests found no signs of cancer. His white blood cell count is back to normal. His lymph nodes are no longer swollen.

He goes back in for another scan in a few weeks, but the doctor told him she isn’t going to recommend any further chemo at this point.

“It was shocking, to tell you the truth. It still is. When I talk about it, I get kind of emotional” about his recovery, he said.

Tim said he was really dreading more chemotherapy. His hair has just started growing back. He can finally taste food again. He wasn’t ready to face more side effects from the treatments, or the COVID–he no longer knows exactly which diagnosis led to his most debilitating symptoms.

He said his ordeal has left him with no patience for health care workers who don’t think they need to be vaccinated.

The way he sees it, it’s no different than the electrical training he had to get before he could wire the lights and pumps in a swimming pool.

“You know, if I don’t certify and keep my license, I can’t work on anything electrical,” he said. "So, if I’ve made the choice, not to go down and take the test and get a license, then I made the choice not to work on electrical stuff."

He supports the growing number of hospitals that have made vaccination mandatory for their workers.

“They don’t let electricians put people at risk,” he said "And they shouldn’t let health care workers for sure."

Chris Bolton and Dejania Oliver contributed additional reporting.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Health News.