Caption

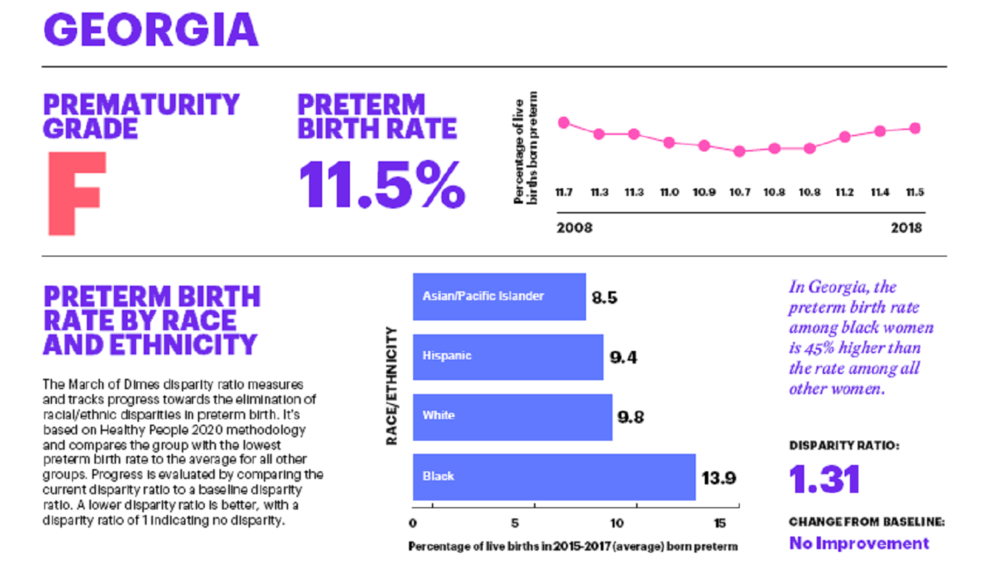

The March of Dimes says the preterm birth rate for Black women in Georgia is 45% higher than the rate among all other women.

Credit: Photo by Kei Scampa from Pexels

|Updated: July 16, 2021 11:58 AM

Health advocates are urging Congress to support Senate Bill 346, aimed at improving health care for Black mothers. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge reports.

The March of Dimes says the preterm birth rate for Black women in Georgia is 45% higher than the rate among all other women.

America is the most dangerous place among wealthy nations in which to give birth, leaders with the March of Dimes and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation say.

"We have this myth that this is the best health care system in the world," RWJF President Dr. Richard Besser said, noting that Black women are three to four times more likely to die than white women, and indigenous women are two to three times more likely to die than white women.

The statistics are not new, and the March of Dimes has been working to raise awareness of just what a national crisis the U.S. has with rates of maternal mortality and preterm birth, March of Dimes President and CEO Stacey Stewart said.

"But there is current action in Congress right now: a proposed 'Momnibus act' that has about 12 different legislative bills included in it," Stewart said. "And pieces of it are making its way through Congress even as we speak."

The Black Maternal Health Momnibus bill was introduced in the House earlier this year. The set of 12 bills would coordinate and fund federal programs to ensure that all pregnant people, regardless of skin color, have access to housing, transportation, food and other needs that influence health.

The majority of the counties in Georgia are considered a maternity care desert, Stewart said, meaning there is limited or no access to obstetric care, no hospital or office obstetric services, and a lack of other kinds of services such as midwives.

The March of Dimes most recently gave Georgia a grade of F.

STUDY: Preterm Births In Georgia Rise For The 3rd Year

The United States overall earned a grade of C, and that's based on the national preterm birth rate, which is a little over 10% and approaching 12% in Georgia, Stewart said.

For Black women in Georgia, it is especially high.

"The Black preterm birth rate is 45% higher than it is for white women," she said.

The March of Dimes says Georgia ranks 45th nationwide for its high number of perterm births. MARCH OF DIMES

The preterm birth rate is a red flag not only for the health of our children but also the health of our economy, Stewart said, because, sometimes, the costs can go up into the million-dollar range if a baby has to stay in a neonatal intensive care unit for months on end.

“Prematurity is the leading cause of death for children between the ages of zero and 5,” Stewart said. “And even babies that may not die as a result of preterm birth often are facing lifelong health challenges.”

Some of those challenges include cerebral palsy, intellectual delays or disabilities, physical disabilities and vision problems, Stewart said.

Women of color are more likely to have preterm babies in the United States.

“I grew up in Georgia," Stewart said. "A lot of times you'd hear family say, ‘Oh, the baby came a little bit early.’ Well, when babies come a little bit early and when they're born too sick and too soon, it can have a devastating impact on their lives over the course of their lives.”

The average cost of a preterm birth in Georgia is $65,000.

Stewart said it’s worth the investment to expand Medicaid coverage, which Georgia lawmakers did.

Rep. Sharon Cooper (R-Marietta) cosponsored a bill that passed last session to extend Medicaid coverage postpartum from two to six months, and allow for lactation care and services.

Now Cooper hopes to further extend postpartum coverage up to a year.

There is a connection between former slave states such as Georgia, the legacy of slavery, and how that legacy and that history has continued and perpetuated over generations, Stewart said.

"We're still dealing with the historical legacy and the impact that's having on Black and brown women today," she said. "And it's something that we are trying to make sure, as a country, we can finally address for the sake of all women and moms and babies, especially those of color."

SURVEY: Many Do Not See Racism As A Barrier To Health Care Access

The health of a woman before she becomes pregnant is a critical indicator of how healthy her pregnancy will be, and because Georgia has not expanded Medicaid, many people do not have access to critical health services, Besser said.

"If this were a problem that were primarily affecting white men in America, we would see a totally different level of attention to this issue," Besser said. "Because it's women of color — Black women in America — who are bearing the brunt of this health crisis, I think that's one of the reasons why we're not seeing more resources coming into to solve this."

Listening to people in communities, considering non-physician birth attendance such as doulas and midwives, and ensuring that those those birth attendants are covered by insurance programs will lead to improvements in maternity outcomes for women.

"We have developed a system in this country where birthing people have become almost solely reliant on delivering their babies in the hospital and going to an OB-GYN for their care," Stewart said. "And while we need a strong hospital system, and we need many OB-GYN providers in the system who are trained and capable of taking care of women across the board irrespective of their race or ethnicity, we should start looking at what other models of care are available and should be available to women to give them additional supports and do what other highly industrialized countries do, which is have a robust system of midwives."

Stewart said health leaders with the March of Dimes and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation are also looking at what can be done to reimagine what is needed to address the health inequity gap and ensure women of color receive culturally competent care.