Section Branding

Header Content

Destroyed in the '70's, Residents Of Black Warner Robins Community Erect Historical Marker

Primary Content

A Warner Robins woman remembers the hot, Georgia summers in the Jody Town Community, a thriving neighborhood in Warner Robins created by the Black workers who helped build Robins Air Force Base.

Shirlyn Johnson-Granville recalls going to the ice cream shop and the owner reaching his whole arm down in the bucket to get her a perfect scoop of ice cream, and she remembers going with her Girl Scout Troop leader to learn how to bake cookies and sew.

“Jody Town was more than a neighborhood. It was a community. We had businesses. We had churches. We had organizations. We had entertainment. Of course, we had this park, Memorial Park, so it was just a hub of life for military men who came from across the southeast to come lay the foundation for Robins Air Force Base,” Johnson-Granville said.

Nearly 50 years after the neighborhood was destroyed by a federal urban renewal program, the community has been memorialized by a new Civil Rights Trail historical marker in Memorial Park.

The Jody Town Community Reunion Committee, the Georgia Historical Society and the City of Warner Robins unveiled the historical marker on June 29.

“It’s just a symbol of what our ancestors did in the past, and we hope it’ll be a symbol for hope and future generations to just know that they can be all they can be as our ancestors and elders thought for us,” Johnson-Granville, who is also the chair of the Jody Town Community Reunion Committee, said.

The history of Jody Town

The Jody Town Community was established in 1943 as a segregated community for the Black civilian employees of Robins Air Force Base, according to the Georgia Historical Society.

For the next 30 years, Jody Town became a thriving community with businesses, churches, entertainment venues and recreational activities at Memorial Park, Johnson-Granville said.

The Warner Robins Jets baseball team played out of Memorial Park where the Dodgers scouted players to join their team, she said.

Rumors of Otis Redding and Little Richard performing at venues in Jody Town before they became famous continue to circle, she said. The first Black funeral home in Warner Robins was built in Jody Town as well.

Johnson-Granville and her family were forced to leave Jody Town when she was 12 years old due to a federal urban renewal program.

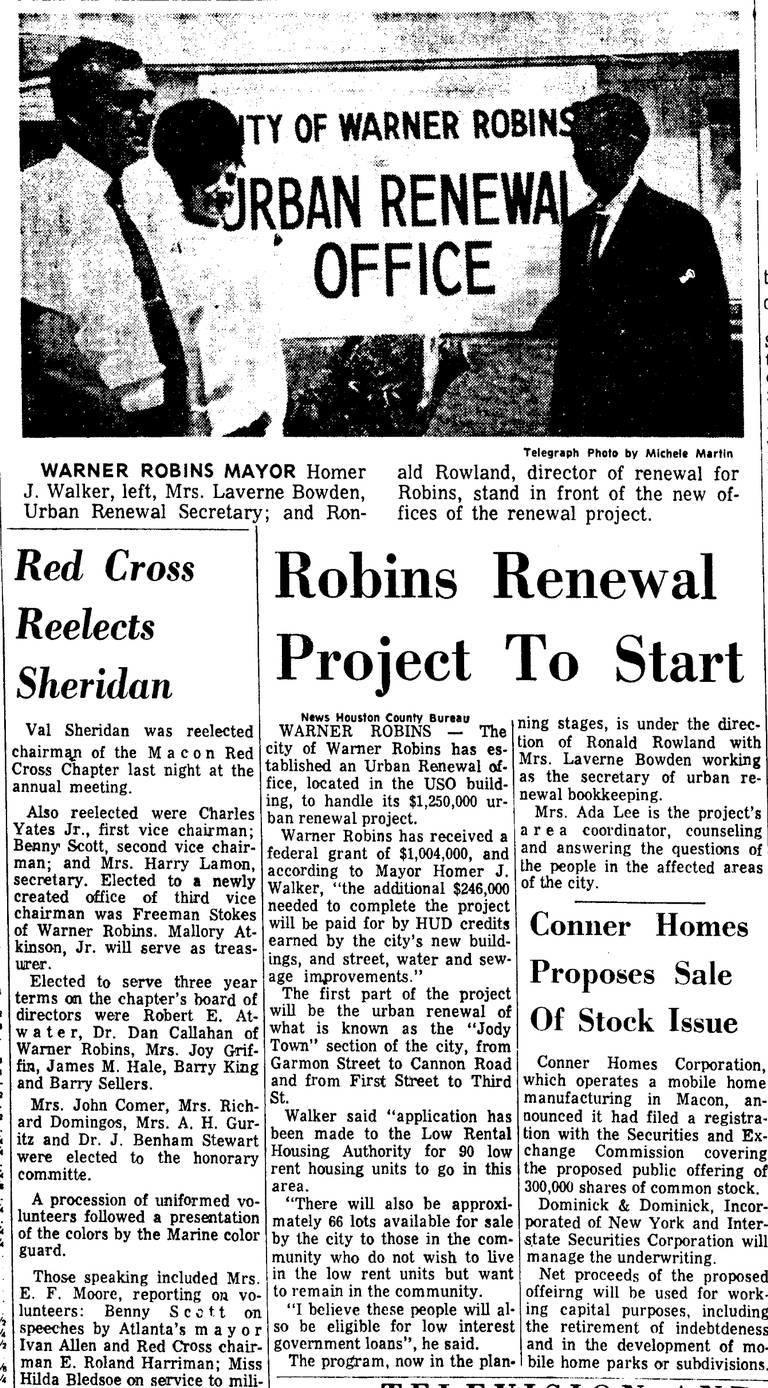

The City of Warner Robins received a more than $1 million grant from the federal government for the “urban renewal” of Warner Robins, and Jody Town was chosen as the first part of the initiative ranging from what was then Garmon Street to Cannon Road and First Street to Third Street, according to Telegraph archives.

The urban renewal programs from the 1950s to 1970s disproportionately impacted Black Americans across the country, and entire neighborhoods were demolished, according to ABC News.

More than 300,000 people between 1955 and 1966 were displaced, according to a report by the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond

“It was really, really sad to leave our community because it’s all we knew growing up,” Johnson-Granville said. “But even though we were sad to leave, we always knew we would try to come back and preserve it. It just took us all these years to do it, but we knew one day we would come back and have reunions and preserve it.”

With the new historical marker, Johnson-Granville said she hopes the legacy of her ancestors will continue and inspire future generations.

“We want the kids who live down here now and live in Warner Robins and across the southeast and across the country to come down and… read the words, see how those men had that motivation, packed up their belongings and said I’m going to move to Warner Robins, Georgia, to work at Robins Air Force Base and to build the base, and that’s that motivation piece we want the current generation, future generations to understand that it’s not your address. It’s your aspiration,” she said.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Telegraph.