Section Branding

Header Content

One Of The Deadliest U.S. Accidental Structural Collapses Happened 40 Years Ago Today

Primary Content

It was another summer night in 1981. Hundreds of people gathered for a "tea dance" at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in downtown Kansas City, Mo., on July 17.

Among them were Karen Jeter, 37, and her husband, Eugene, 48, who had just gotten married a couple of weeks earlier.

"She was a really good dancer. Loved to dance, loved music. She's the one that taught me how to dance," said Karen's son, Brent Wright. "They were really wonderful people."

Television crews were also at the Hyatt Regency that night to cover the social event in the hotel's lobby. Years later, Wright would watch footage of Karen and Eugene Jeter on a national news show.

"They had captured this video of my mother and my stepfather dancing, laughing, just having a great time," Wright said.

"It's a really nice thing to know that at least that night they were enjoying themselves and living their lives to the fullest, you know, still newlyweds," he said. "Initially, after a tragedy like that, those things are hard to watch."

The news clip captured what were some of the Jeters' final moments.

They were among the 114 people who were killed at the Hyatt Regency that night when two elevated walkways broke free from their support rods and collapsed onto the crowd below, injuring more than 200 and leaving a crumpled heap of rubble for rescuers to dig through.

It remains one of the deadliest accidental structural building failures in U.S. history and is drawing parallels to the recent condo collapse in Surfside, Fla., that killed nearly 100 people roughly 40 years later.

How the Hyatt Regency collapse unfolded

In 1981 — the same year the Champlain Towers South condo building in Surfside was constructed — the Hyatt Regency Hotel some 1,500 miles away was enjoying its second summer open to the public.

The concrete "skybridges" floating above the lobby were a marquee feature of the new, 40-story hotel in the middle of Missouri's largest city.

They would also be what doomed it. After the collapse, investigators would conclude that a seemingly minor design change contributed to the disaster.

The elevated walkways were held up with rods connected to the atrium roof. But the second-floor walkway was connected to the fourth-floor walkway — not the roof. That meant that the fourth-floor walkway was taking on double the intended load.

As the July 17 tea dance went on, the crowd grew in the lobby as well as on the skybridges, where onlookers gathered to get a bird's-eye view of the festivities below.

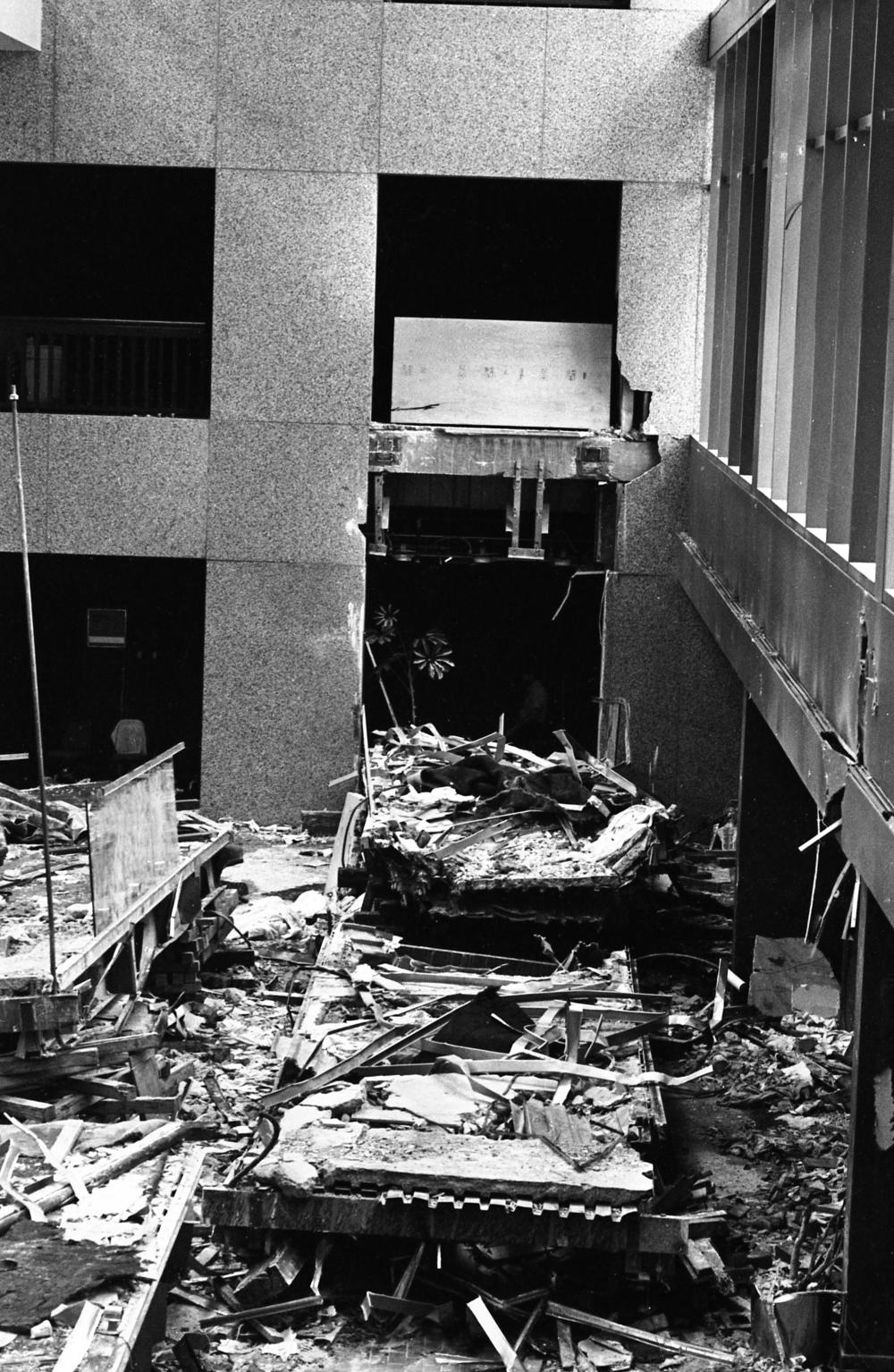

Then, suddenly, the second- and fourth-floor skybridges began swaying before collapsing and crashing down into the lobby, killing some revelers and trapping others beneath the broken concrete.

Dr. Joseph F. Waeckerle, who had recently resigned as Kansas City's medical director to take a position at a local hospital, was among the first responders on the scene.

"You have to understand the chaos and the carnage that had gone on in that lobby. The water was flowing, the mains were cut when the skywalks collapsed. Electrical wires were hanging and arcing and sparking. There were no lights," Waeckerle said.

He said he spent roughly 12 hours in the hotel lobby, overseeing rescue triage operations for those who had survived the collapse.

Even for Waeckerle, who had responded to other disasters, the scene at the Hyatt Regency came as a shock.

"Like everybody else, I shut my eyes for a moment and said, 'Gee whiz, what am I doing here?' and said a little prayer and prayed that I could do the best I can," he said. "And then got on with it."

Rescue workers toiled throughout the night, using cranes and other heavy machinery to move the massive pieces of concrete that made up much of the pile. First responders went to great lengths to extract victims who were pinned under immovable debris, at times amputating their limbs to get them out.

For Wright, it wasn't until the next morning that his father and stepmother, who had also been at the tea dance, told him and his sister that Karen and Eugene Jeter had died.

"It was unimaginable. You never expect that kind of news, especially when you're a kid. And to say it was difficult is an understatement," Wright said. "Part of your initial reaction is shock, and it's almost too horrible to even believe."

It would take months, if not years, for Wright and the other families of the victims to get answers about how something so unimaginable could have occurred during such a joyous occasion.

Lessons learned

After the collapse, the engineering firm that signed off on the plans for the skywalks lost its license, and the Hyatt Regency's owner paid $140 million in damages to victims' families.

The deadly structural failure is still closely studied by civil engineers and serves as a cautionary tale for similar designs.

Waeckerle said first responders also learned lessons after working on the collapse site, such as how to improve communications, which he said is "always the biggest problem" in a disaster.

"For example, initially we used a bullhorn, and that shorted out very quickly when you got doused with the water," he said. "Then it was dark, and so people yelled and screamed. And then we sort of got organized."

He urged first responders continuing their search at the Surfside condo collapse to adhere to the formal rules of emergency management but also maintain an emotional connection to the victims and survivors.

"Follow command and control. Follow communications. Never give up hope. And never give up respect for your patients," Waeckerle said.

Wright, who now helps run the Skywalk Memorial Foundation to honor the victims of the collapse and the first responders who rushed in to help, said he understands what many families of those lost in the Surfside disaster are going through.

"I've thought about all those people down in Florida every day since that event happened," Wright said in a recent interview. "I can only hope they have friends and family with them to give them hope and to give them comfort and take them through what are unimaginably difficult days."

Wright urged the victims' loved ones to continue their search for answers about what happened, and he acknowledged that for many, a period of agonizing grief remains ahead.

"But be patient. Sit with those people who love you and who you love and take it one day at a time. Eventually you'll see a little bit of light at the end of the tunnel. And with all of that, you'll make it through. I know you can."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.