Section Branding

Header Content

A Research Vessel Found SpongeBob Look-Alikes A Mile Under The Ocean's Surface

Primary Content

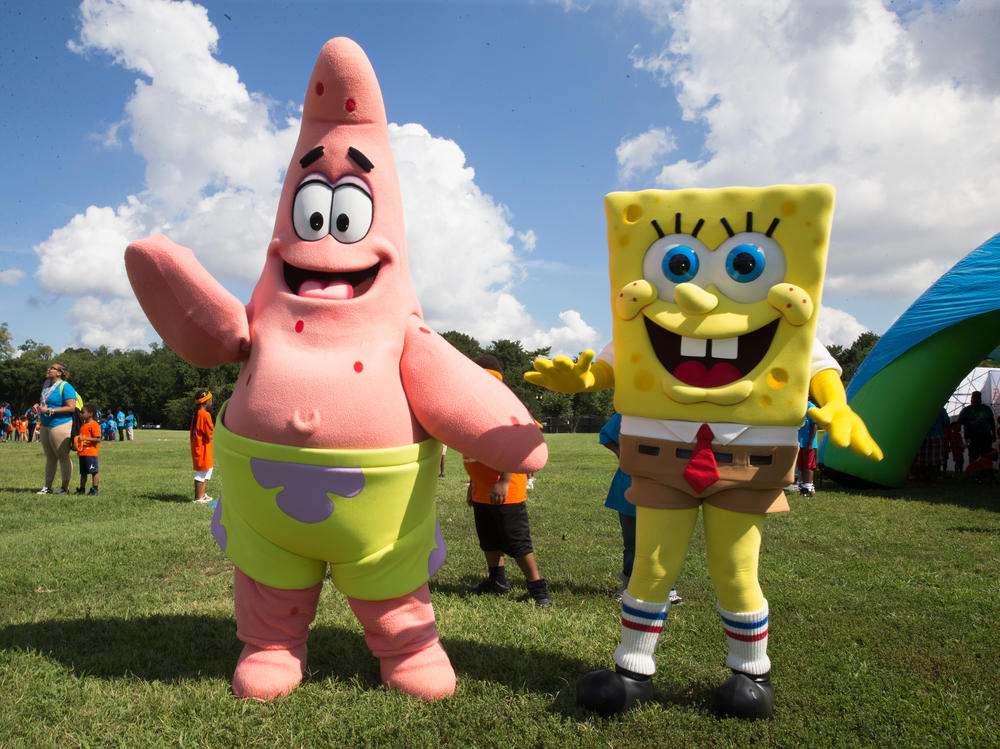

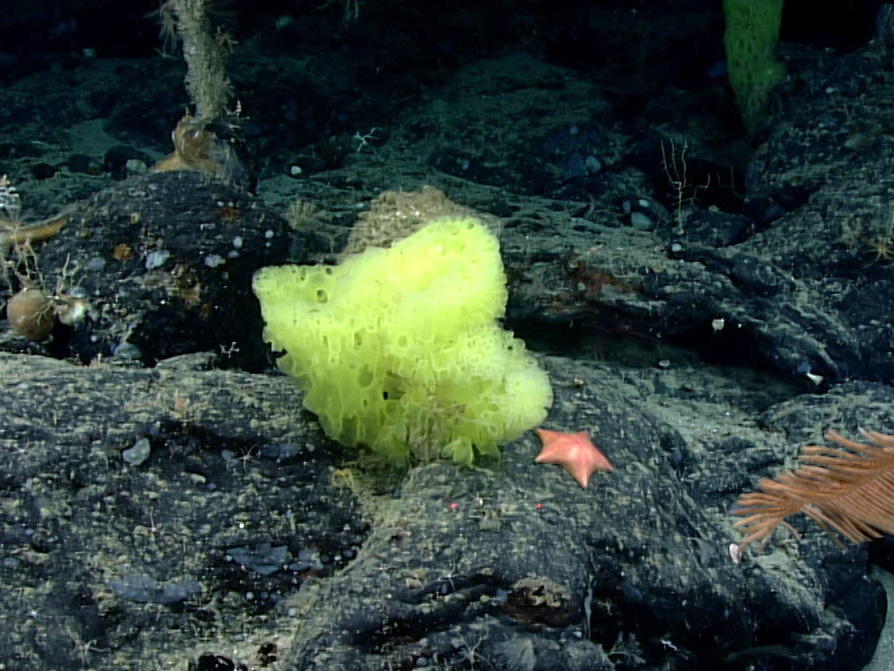

An ocean expedition exploring more than a mile under the surface of the Atlantic captured a startlingly silly sight this week: a sponge that looked very much like SpongeBob SquarePants.

And right next to it, a pink sea star — a doppelganger for Patrick, SpongeBob's dim-witted best friend.

Christopher Mah was one of the scientists watching a live feed from a submersible launched off the NOAA ship Okeanos Explorer. He's a research associate at the National Museum of Natural History who frequently collaborates with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. He's also an expert on starfish.

Mah immediately noticed the underwater creatures' resemblance to the animated buddies. "They're just a dead ringer for the cartoon characters," Mah tells NPR.

So he tweeted an image of the two noting the resemblance, delighting lots of folks. Someone helpfully added faces and legs.

Bad news: Sponges and sea stars aren't actually pals

Rather than chilling together under the sea, Mah suspects a different reason for the creatures' closeness: Sea stars like to feed on sponges.

"In all likelihood, the reason that starfish is right next to that sponge is because that sponge is just about to be devoured, at least in part," he says.

Or maybe not. The sponge might be bright yellow because of its chemical defenses, Mah says.

Either way, he says, "The reality is a little crueler than perhaps a cartoon would suggest."

In scientific terms, a sponge is Hertwigia, while a starfish is a Chondraster.

Mah says the starfish spotted by the expedition was probably a species called a Chondraster grandis — the pink starfish that was likely the inspiration for the Patrick character.

While the real-life sponge is as yellow as the Nickelodeon character, SpongeBob's shape is far from what's found in nature.

"SpongeBob is obviously shaped like a plastic cleaning sponge — he's rectangular," Mah says. But actual deep-sea sponges? "They're almost surreal. They're bizarre, crazy shapes."

Patrick's anatomy is not exactly faithful to that of a real starfish, either.

The expedition was exploring the depths of the Atlantic

The expedition was more than 200 miles off the Atlantic coast when the now-famous sponge and starfish were sighted.

The find was part of NOAA's North Atlantic Stepping Stones, a monthlong expedition on the Okeanos Explorer to collect information about unknown and poorly understood deep-water areas off the eastern U.S. coast and high seas. The expedition involved mapping the seafloor and explorations of deep-sea coral sponge communities, fish habitats and the ecosystems of seamounts, which are underwater mountains.

Deep-sea life is poorly understood

Is the fuss over a real sponge that looks like an animated sponge a bit silly?

Absolutely, says Mah. But he welcomes the attention if it means that people think about the life that is dwelling in the world's oceans.

"These are literally animals that the public might not have ever even seen before. They live at almost a 2,000-meter depth," he notes.

He hopes the hubbub brings awareness not only to sponges and starfish but also to their habitat, which is under threat from forces including mining and fishing.

The positive response from folks on Twitter has been nice, too.

"They're like, 'Oh, my God, this is perfect. This is great. I can't believe this is true,' " Mah says. "So if we can bring positivity and we can make people happy by showing them nature — well, that's what nature has always done for us before."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.