Section Branding

Header Content

Controlling The Border Is A Challenge. Texas Gov. Abbott's Crackdown Is Proving That

Primary Content

The Mexico-U.S. border in Texas is again the backdrop for a set of hardline policies designed to discourage migrants from crossing the Rio Grande. This time, the instigator is Gov. Greg Abbott—a 63-year-old Republican running for his third term as Texas governor, who's hoping tough talk on immigrants will capture Trump's fanatical followers in Texas.

"We're not playing games anymore," Abbott said recently on Fox News. "And we have a new program in place because the Biden Administration plan is to catch and release. The Texas plan is to catch and to jail."

Abbott has launched a border crackdown that is strikingly similar to former president Trump's harsh immigration agenda. It's called "Operation Lone Star," and includes jailing asylum seekers, making disaster declarations and building a border wall. It goes even further. Abbott ordered his state highway patrol to interdict any vehicles—even commercial buses—suspected of carrying unauthorized migrants, though that action has been blocked by a federal judge.

Critics say some of the measures are blatantly unconstitutional.

Lacking the immense powers of the federal government, the Texas border initiative has not lived up to its hype.

How Abbott's border crackdown "Operation Lone Star" works

Abbott has fashioned his own Texas Border Patrol made up of state troopers, National Guard, and reinforcements from other red states, with him as commander-in-chief. Their mission is to do something about the surge of migrants crossing the Southern border—a goal the Biden Administration has so far failed to accomplish. Abbott says he is responding to complaints from border residents and ranchers who say they are being overrun.

Ground zero for the governor is Del Rio, a friendly border city of 35,000 in the West Texas scrub desert that has become the second busiest region for illegal crossings on the Southern divide. Agents apprehended 1,000 people a day in June, a 500% jump over past year.

The state strategy is to post "No Trespassing" signs on private properties along the river, then when an immigrant steps onto the bank, nab him for trespassing, which has been upgraded to a Class A misdemeanor.

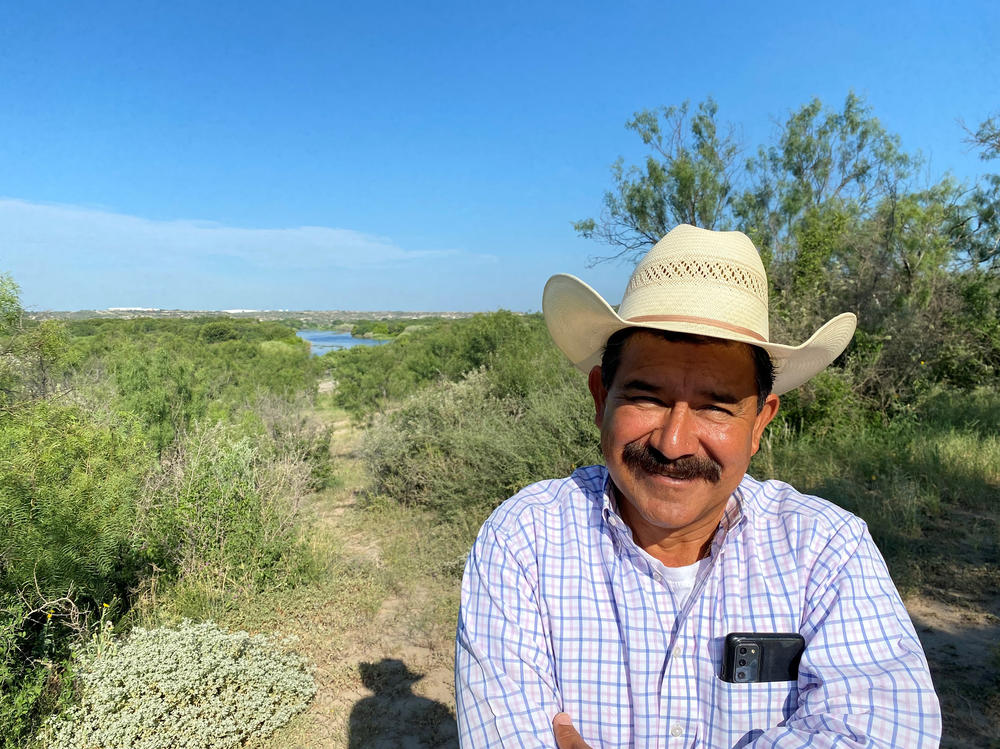

One morning last week, Val Verde County Commissioner Gustavo "Gus" Flores, who has 90 miles of river border in his precinct, hopped in a county pickup truck to give a tour to a reporter. He has a bushy mustache and wears a white cowboy hat.

"We're going down to the river area where it's a hotspot," Flores says. "A lot of immigrants are crossing through there."

But as he drives along rutted county roads between stands of thick carrizo cane, there are no immigrants to see, just black and white SUVs with the Texas Department of Public Safety and Humvees driven by bored National Guard troops.

What's happened is the human smugglers and the migrants have changed tactics. As soon as word got back that cops were arresting migrants on private property, now the vast majority are crossing downstream on federal property.

"The coyotes are getting informed (where are) the good spots to move people through," Flores says. "They have learned if they stay in federal land ... the state really can't touch 'em."

The governor was so certain his state police would be locking up multitudes of trespassers that—with great fanfare—he opened a special booking center in Del Rio and cleared out a prison in South Texas and converted it into a jail. Yet for the past two weeks, state police have been making only about eight arrests a day.

Val Verde County Attorney David Martinez, the official responsible for prosecuting the trespassers, says he was told to expect as many as 200 migrant arrests a day.

"Obviously at 200 a day that's 1,000 arrests a week. We certainly have not approached anywhere near those numbers," he says.

Abbott's border dragnet has not stopped immigrant flows but is popular with landowners

Meanwhile, every day hundreds of migrants continue to wade hip-deep across the international river and surrender to Border Patrol agents on federal property where they know they'll be booked and released. In fact, on the commissioner's riverside tour, as soon as he parked his truck near the international bridge, two large groups of mostly Haitian nationals were spotted sitting quietly inside of Trump's border wall while agents prepared to process them.

While the governor's border dragnet has not made a dent in the immigrant flows, it has been popular among some landowners. The state is paying to erect 8-foot chain-link fences topped with concertina wire on private borderland.

"Let me tell you," Flores says, motioning to a gleaming new silver fence, "this landowner here didn't have a damn fence. Now he's got a brand new fence." The commissioner also owns property on the river, where he rents a house and runs some cows, and he says he's looking forward to signing up with the state.

"Oh, hell yeah," he says, "It's your fence at the end of the day."

Local officials appreciate that the state is trying to help them out. County Attorney David Martinez, a democrat, says the situation is unsustainable; the feds cannot keep releasing immigrants onto the streets of Del Rio.

"We're not set up for this," he says. "Without a doubt, it's an issue that needs to be addressed or a lot of us over here are gonna be in trouble fast."

Border Patrol overwhelmed by number of migrants, politicians and locals are unhappy

In fact, they're already in trouble.

In Del Rio, the Border Patrol is so overwhelmed they're holding migrants in open-air corrals under the international bridge. They're also being penned under a bridge in the Rio Grande Valley—where agents now regularly encounter 3,000 immigrants a day.

Customs and Border Protection apprehended 210,000 crossers in July, surpassing a 20-year high on the Southern border, though many of them are the same people who cross again and again. Under the controversial Title 42 public health order, the Biden administration, as did Trump before him, expels them to Mexico or their country of origin in order to prohibit entry of persons who potentially pose a health risk. Critics such as the ACLU say the policy is unlawful because it turns back legitimate asylum seekers.

CBP declined to comment on the large number of apprehensions, which normally decline in the hot summer months but have remained high this year.

While Biden has kept Title 42 in place, conservative governors, such as Abbott, have blasted the president for loosening Trump's hardline immigration policies. The Trump administration had, in fact, sharply reduced arrivals of asylum seekers, but civil libertarians said it did so by massively violating human rights.

Even reliably Democratic politicians on the border are unhappy these days. In the last two weeks, the City of Laredo has sued the Biden Administration and Hidalgo County has declared a local disaster, both actions intended to get federal officials to stop releasing immigrants into their communities because all the shelters are saturated.

Hidalgo County Judge Richard Cortez, a democrat, wrote a letter to Biden calling the situation "extremely pressing."

"It's a very serious problem because we have immigrants coming into all parts of our county and they're loitering around our parks, they're coming into our cities. We're very close to a point that is unmanageable," Cortez said in a telephone interview.

Locals are upset, too.

On Veterans Blvd, the main thoroughfare in Del Rio, clusters of asylum seekers linger around a Stripes convenience store, waiting for the first in a series of buses to take them to their destination cities where they'll await their court dates.

Last week, a Venezuelan man stood in front of the Whispering Palms Motel explaining why he, his wife and infant son fled Caracas for Texas. He said the Venezuelan government was persecuting him because he belongs to an opposition party. The innkeeper burst out of the lobby to have her say.

"Don't just drop 'em on the streets," said Maria Cannon. "Have a plan for them. Have something for them."

While Cannon is distressed at all the immigrants the Border Patrol is releasing in Del Rio, she's dubious of the heavy state law enforcement presence in town.

"Because it's not going to help anything. They (migrants) are still going to come across. And you know what? I don't blame them for coming. The thing is this—they're suffering."

"Abbott cannot seek to enforce his own version of immigration policy"

Gov. Abbott keeps adding new executive orders to Operation Lone Star.

Bulldozers have cleared ground on riverside state land in neighboring Eagle Pass, where he vows to restart Trump's "unfinished border wall" using $250 million in diverted state funds, and $900,000 more in donations. The effort is not expected to yield more than a few miles of additional border barrier.

"Abbott can't simply build a border wall wherever he wants," says Terence Garrett, a political science professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, pointing out that the state does not possess the power to condemn land along the border as the federal government can. "But talk is cheap. This is a tried-and-true method used by former President Trump, and now Gov. Abbott, to generate political support."

Last week, Abbott ordered state troopers to interdict any vans or buses carrying migrants released by the Border Patrol—saying the passengers may have Coronavirus. The Justice Department promptly sued. And on Tuesday, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order that Abbott was likely overstepping his powers.

On Thursday, the ACLU announced it is suing Texas on the same grounds.

"Gov. Abbott cannot seek to enforce his own version of immigration policy," said Kate Huddleston, a lawyer with the ACLU of Texas. "That's because the federal government, not states, not local governments, sets immigration policy and enforces immigration law."

While the efficacy of Abbott's border crackdown remains elusive, it has resulted in one concrete result. Earlier this summer, Trump endorsed Abbott's bid for reelection.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.