Section Branding

Header Content

The FBI Keeps Using Clues From Volunteer Sleuths To Find The Jan. 6 Capitol Rioters

Primary Content

As rioters made their way through the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, many of them livestreamed their actions and posted photos and videos on social media. That steady stream of content created an enormous record of evidence that law enforcement needed to sift through to build cases against the accused.

Now, more than 575 federal criminal complaints have been filed, and a striking pattern has emerged: Time and time again, the FBI is relying on crowdsourced tips from an ad hoc community of amateur investigators sifting through that pile of content for clues.

These informal communities go by a number of names: Some go by the moniker Sedition Hunters. Others call themselves Deep State Dogs. Together, they amount to hundreds of people who since Jan. 6 have dedicated themselves to helping law enforcement track down suspects.

Their cumulative work represents what is likely the largest spontaneous, open source information collection and analysis effort ever conducted by volunteers to assist law enforcement. Sedition Hunters are mentioned by name in at least 13 cases, other complaints reference specific social media handles of volunteers, and still more refer to evidence voluntarily submitted by tipsters — many of whom do not seem to know the accused — citing information on public platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube or Parler.

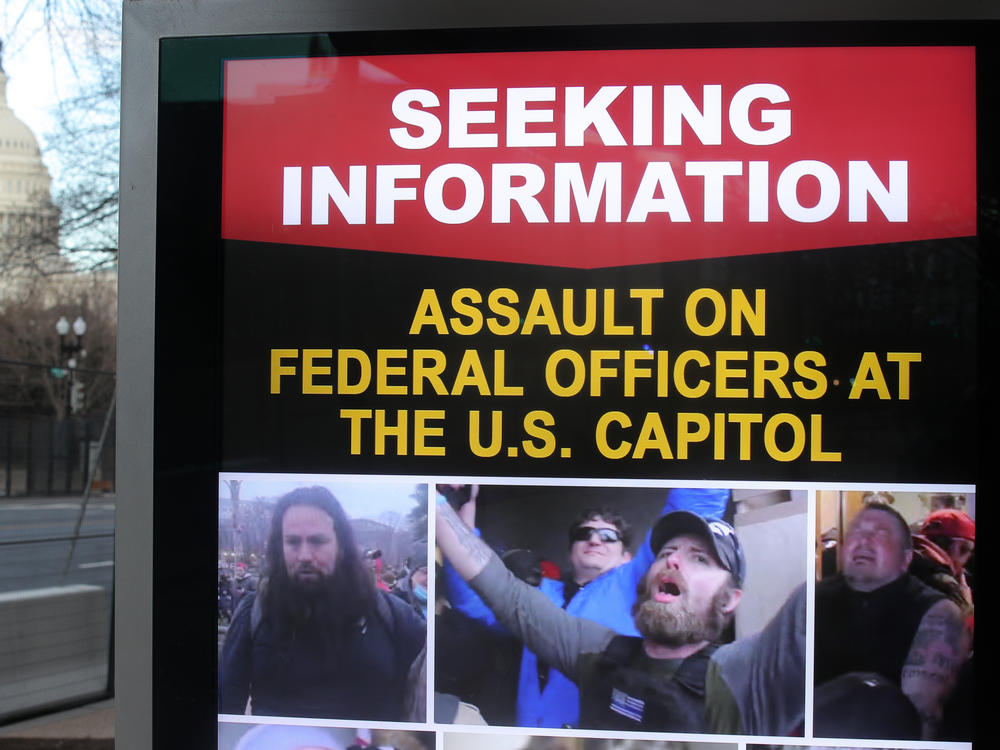

Investigators are facing a mammoth task

Part of their rise was perhaps by necessity: Federal investigators were facing a gargantuan mountain of public — or open source — evidence.

"I believe 9/11 was not as complex as this," said Greg Hunter, a defense attorney who has worked on the cases of a number of individuals charged in the insurrection. "The evidence is significantly more complicated for [the government] than they thought it was going to be. That's clear. ... They say that this is the most complex thing they've ever done."

This may have opened up an opportunity for Americans, many with no formal training in intelligence or law enforcement, to lend a hand.

"The FBI, of course, was overwhelmed with this mammoth task of identifying these individuals, the Sedition Hunters community, everyone started individually reviewing all of the footage," said Forrest Rogers, an American who is a member of the group Deep State Dogs.

The FBI's National Threat Operations Center saw a 750% rise in calls and electronic tips following Jan. 6, the bureau told NPR.

"The FBI encourages the public to continue to send tips to the FBI. As we have seen with dozens of cases so far, the tips matter. Tipsters should rest assured that the FBI is working diligently behind the scenes to follow all investigative leads to verify tips from the public and bring these criminals to justice," said Samantha Shero, a spokesperson for the FBI.

"What can I do to help prevent this?"

The volunteers who came forward to help the FBI had different motivations, but many felt a need to contribute to the effort to bring those involved in the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection to justice.

"I saw an attempted coup happen, and I never want to see that again. So for me, it was: What can I do to help prevent this?" said a Sedition Hunter named Kay, a 34-year-old stay-at-home mother in Washington state.

Kay, who requested her last name be kept private, has spent hundreds of hours looking at videos from that day in her free time. "I don't live anywhere near D.C. I have no political power. I'm just an ordinary person, really. But this was something I felt I could do," she said.

Kay began annotating videos, creating a spreadsheet where things spotted in videos could be listed: a person wearing a pink hat, for example. By using these cues, volunteers could compare different video angles to identify people committing alleged crimes.

Tommy Carstensen, a Danish citizen, said he's watched thousands of videos since January. One tactic he used was to analyze the music playing in the background in various videos of the riot.

"Someone later created a playlist, and then if you heard Elton John, you would know, OK, this is at 2 p.m. ... and then you could say, OK, this individual was at that location at this time," Carstensen said.

Some of these groups have had some measurable success in aiding law enforcement. The group Deep State Dogs was able to identify the person who allegedly used a Taser on Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police officer Michael Fanone on the Capitol steps, even when law enforcement was apparently unaware of the person's identity.

Rogers slowly watched every single frame of the incident and focused on watching the hand of the individual holding the Taser.

"We located the suspect in different places throughout that event where he was carrying the Taser in his hand," Rogers said. "Also, we found him with a frontal, and then we put it together as a compilation, submitted it to the FBI to make it easier for them to indeed identify."

Law enforcement later publicly identified that individual as Daniel Rodriguez, who has since been charged with a number of serious offenses. As part of the filings in the case, federal prosecutors cited two Deep State Dogs videos that were in their possession.

The use of this open source intelligence — publicly obtainable information — is a new twist on a longtime law enforcement tool.

"If we came back to the Wild West times of wanted posters, that's a form of open source intelligence, where they just have the sketch of the bank robber," Rogers said. "It's just because of the internet and everyone's — unexplainable, in my opinion — need to broadcast all of their private information to the world that open source intelligence is becoming much more lucrative when it comes to identifying people."

The use of facial recognition technology

Some of these volunteer sleuths, such as Carstensen, have also turned to facial recognition software to aid their efforts. It's a controversial tool that he acknowledges has broader shortcomings.

"I don't really like facial recognition when it's put in the hands of [a] government, say, China monitoring the Uyghurs," he said. "But in this case, it's all public video, from a public location."

But American law enforcement is also independently employing this technology to make the case against Jan. 6 suspects. Documents in at least a dozen cases cite the use of facial recognition software.

For example, suspect Stephen Chase Randolph, who has been charged with among other things assaulting a U.S. Capitol Police officer, was identified when the FBI used open source facial recognition to match a photo from the insurrection to the Instagram account of an acquaintance of Randolph's.

Mitch Silber, former director of intelligence analysis for the New York City Police Department, said this technology is typically only used sparingly by law enforcement.

"Law enforcement in general, when they're sort of at wits' end, and they haven't been able to make progress in identifying a suspect for a particular crime, it's sort of the move of last resort," Silber said.

But civil liberties advocates said that even if the use of this technology in these cases could be seen as a force for justice, the fundamental tool is dangerous.

"We know that many politicians and many police departments with this power would be, frankly, more likely to go after Black Lives Matter protesters than to go after insurrectionists," said Adam Schwartz of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital civil liberties advocacy organization. "We support efforts to bring those insurrectionists to justice, ... [but] face recognition technology in the hands of the government is so dangerous that we think the government should not be using it at all."

Schwartz said that it was notable law enforcement was so openly using facial recognition technology to support criminal cases, and that doing so now may be strategic.

"It is common for the law enforcement community to try to work the public in favor of a surveillance technology by not talking much about the technology until the right sympathetic case comes along, and then they talk about it a lot," Schwartz said.

But livestreaming as well as public posts, including video and photos, are realities of mass political events in our time. So the use of crowdsourcing and facial recognition associated with the Jan. 6 charges is not just unprecedented — but likely points to a trend that these tools will be used more frequently in the future.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content