Section Branding

Header Content

Chuck Close, Creator Of Gigantic Portraits, Has Died At 81

Primary Content

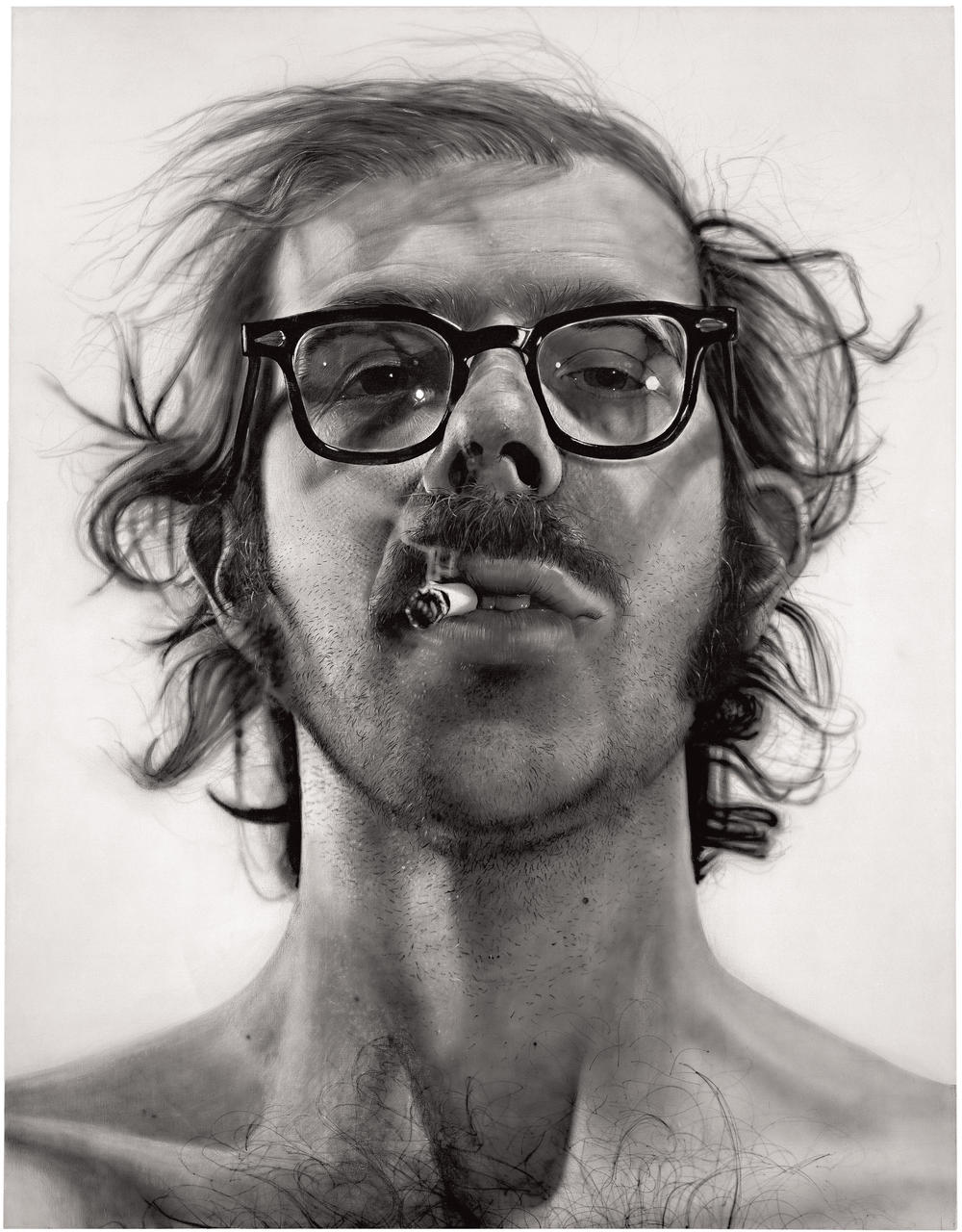

Chuck Close's face made him famous — his face on canvas, that is. Gigantic, up close and personal, his black and white 1968 Big Self-Portrait leaves nothing to the imagination. You can see every spike of stubble, every wisp of uncombed hair, every curl of smoke from his cigarette. It was a bold opening statement from someone who went on to become one of the best-known portraitists of his generation, who died today at age 81.

Close was born in Washington State in 1940, and as a child struggled with what he later realized was dyslexia—but art was never a struggle. His parents encouraged him, paying for art supplies and lessons; he told the New York Times Magazine in 1998 that he remembered staying up late, poring over magazine covers with a magnifying glass, ''trying to figure out how paintings got made,'' which might perhaps have been a hint at where his career would ultimately go.

How the big heads were made

Close didn't just work in paint—he was a photographer, a printmaker, even a weaver. But he's best known for those big heads, the pixelated portraits of himself and his art-world friends that he made by breaking down photographs into intricate grids and then blowing them up, reproducing them square by painstaking square onto oversized canvases. He even developed a system with a forklift, a platform, a chair and a rope that let him maneuver around the whole painting easily.

Close's style changed over time. He added color in the 1970s, and drifted away from the strict photorealism of Big Self-Portrait towards a brushier, looser look. But he was forced to make a drastic change in 1988, when a collapsed spinal artery left him mostly paralyzed from the neck down. He eventually learned to paint again using brushes strapped to his hands with Velcro, and canvases his assistants prepped with grids. Some of Close's later works show a loopy psychedelicism: each grid square might be accurate, or it could just as well hold a colorful blob that looks like a target, a hot dog or a teardrop until you step back to experience the whole.

Allegations of sexual harassment

Close found great success in those later years, snapping Polaroids of movie stars and painting former president Bill Clinton. But he also faced allegations of sexual harassment; several women came forward and said he'd made inappropriate comments about their bodies and private lives when they came to his studio to pose for him.

"If I embarrassed anyone or made them feel uncomfortable, I am truly sorry, I didn't mean to. I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but we're all adults," Close told the New York Times. The National Gallery of Art canceled a show of Close's work in the wake of the allegations.

Close was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia in 2015—a condition his neurologist said could have accounted for some of his behavior. He died of congestive heart failure at a hospital in Oceanside, New York; survivors include daughters Georgia and Maggie and several grandchildren.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content