Caption

J.C. Lewis Primary Health Care opened a pop-up vaccination center in Oglethorpe Mall in Savannah.

Credit: Jacqueline GaNun/The Current

|Updated: August 26, 2021 5:18 PM

J.C. Lewis Primary Health Care opened a pop-up vaccination center in Oglethorpe Mall in Savannah.

Jacqueline GaNun, The Current

When Beatriz Severson was eligible to get her COVID-19 vaccine, she signed up for an appointment right away. She was eager to see her 88-year-old mother, who lives alone in Bogatá, Colombia, but she wouldn’t dream of taking her first trip since September 2019 without certainty that she wouldn’t bring the virus with her on a trip.

“I was just counting the days, and counting the two weeks after she got vaccinated, making sure that she was fully protected,” Severson said. “That opportunity to be with loved ones, and have a peace of mind that really, you are protected, and you’re protecting them, doesn’t have any price.”

Since her safe trip to Columbia in May, Severson has become part of a Savannah-based team working to overcome vaccine hesitancy in Chatham County, especially among people of color, as the area’s fully vaccinated percentage has plateaued around 44%.

While Chatham’s average is slightly higher rate than Georgia’s overall vaccine rate of 42%, it falls woefully short of the levels needed to achieve “herd immunity,” when enough of the population is vaccinated in order to protect those who can’t be, such as children and immunocompromised people.

As of Monday, 93.5% of the ICU beds were full in the 13 counties including Chatham grouped together by Georgia’s Department of Public Health. Most of those beds are located in Savannah’s medical centers, such as Memorial Health, where the “vast majority” of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 are unvaccinated, said Dr. Stephen Thacker, Memorial’s associate chief medical officer.

According to Thacker, most patients coming down with COVID are infected with the delta variant, and the spread is occurring because of relatively low vaccination rates.

“This virus is so contagious, right now, and we have so many members of our community that are not vaccinated, that this really will spread like wildfire through our community,” Thacker said.

Beatriz Severson is one of an army of public health volunteers trying to stem this contagion. Working with the Coastal Georgia Indicators Coalition, Severson promotes vaccine outreach among Hispanic and Latino communities in the area.

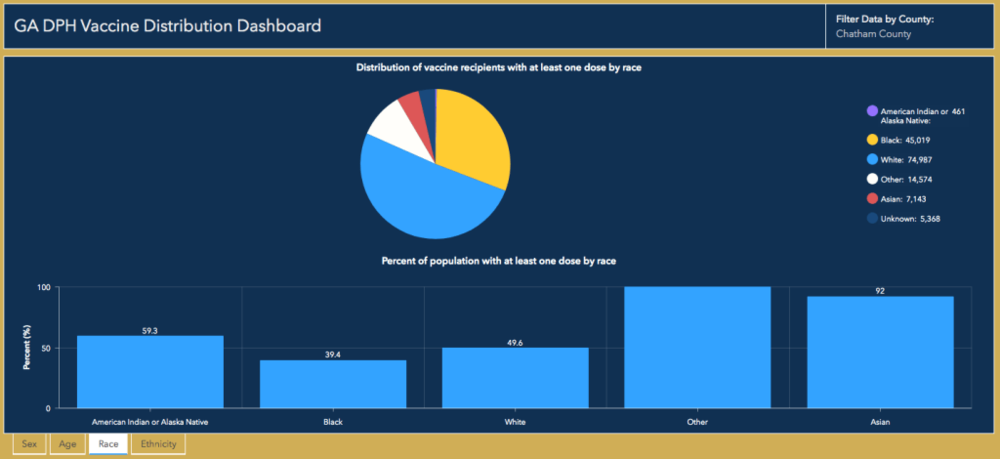

Nearly 50% of the white population in Chatham County has gotten at least one dose of the vaccine, according to Georgia’s DPH. The Black population has a vaccination rate of 39.4%, and rates among Hispanics is even lower at 33.8%.

Georgia Department of Public Health statistics on Chatham County’s vaccination rate by race as of Aug. 25, 2021. Numbers are for one dose.

Targeted public health outreach to communities of color has stepped up this year, thanks to help from Dr. Elsie Smalls and Paula Kreissler of Healthy Savannah, who have focused on better health education and access for Chatham County for several years.

Before the pandemic, Healthy Savannah’s focus was on daily wellness, including fitness, nutrition and connecting people to health clinics. Over the past five years, it’s received approximately $4 million in funding from the Centers for Disease Control for programs with a racial and ethnic approach to community health. Those programs were focused on physical activity and nutrition, and because of Healthy Savannah’s previous involvement with the CDC, it received funding for a COVID-19 and flu supplemental grant focused on vaccine equity and reaching underserved populations, Kreissler said.

The organization has taken a low-tech approach to finding out core roots of vaccine hesitancy in these marginalized communities. They conduct listening sessions with residents. What they have learned is that low-income neighbors without transportation or a cellphone have a harder time signing up for and receiving a vaccine. And disinformation about cost may have been discouraging people.

The COVID-19 vaccine is completely free, regardless of insurance or immigration status. But some sites offering vaccine appointments online ask for insurance information, adding to confusion over whether the vaccine was free, according to Smalls, who is the operations manager of the 18-month CDC grant.

While those barriers can be overcome — at least 75 mobile vaccine clinics have been held this year — a harder challenge is overcoming the mistrust of the medical community among communities of color. This concern stems from historic injustices toward Black communities such as as the infamous 20th-century study in Tuskegee, Alabama, where doctors withheld widely available syphilis treatment from Black men.

“That’s one of what we hope to do in those listening sessions is opening up a dialogue” about past medical malpractice toward people of color, according to Smalls. Her group strives to have “a respectful and engaging conversation around that, and figuring out where we go from here in this place that we’re in,” she said.

Along with the community conversations hosted by Healthy Savannah, one aspect of the program is its “trusted messengers,” people who attend training and then encourage members of their community to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Healthy Savannah’s CDC supplemental grant partners include J.C. Lewis Health Care Center, the Chatham County Health Department and St. Joseph’s Candler Hospital, Smalls said. The organization receives reports from both grant partners and community partners who work more independently of Healthy Savannah, like the Coastal Georgia Indicators Coalition.

In her volunteer capacity at the CGIC, Severson works as a conduit to encourage the vaccine among Hispanic and Latino populations in Chatham County. Severson said the CGIC has gotten more than 300 shots in arms.

Rena Douse follows the four T’s — time, transportation, technology and trust — in her work at J.C. Lewis Primary Care Health Care.

Douse, a licensed nurse practitioner, is the CEO of J.C. Lewis and has overseen a push for COVID-19 vaccinations through the health center, thanks in part to funds from the Healthy Savannah’s CDC grant.

Her clinic’s services are also federally funded and provide affordable (in some cases, free) health care for people who are uninsured or can’t afford health care based on a sliding scale of how much a patient can afford to pay.

Because of its connections to people who are low-income, J.C. Lewis has been a particularly accessible place to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, which is free to all. The clinic has vaccinated more than 3,000 people against COVID-19, according to Douse.

J.C. Lewis has an ad campaign encouraging vaccinations involving radio ads, billboards and ads on social media. Still, a key concern Douse sees among her clients involves their immigration status. They were worried about health clinics requiring personal information they may not have if they are undocumented.

Douse tells them that the vaccine is free and available to everyone regardless of income or immigration status.

To address issues of transportation and technology, J.C. Lewis also has mobile COVID-19 vaccine clinics. “We promote that the vaccines are safe, and we believe that they are safe,” Douse said.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, an independent, in-depth and investigative journalism website for Coastal Georgia.