Section Branding

Header Content

Voting Advocates Say Women's Equality Day Has A Complicated (And Yes, Racist) History

Primary Content

Women's Equality Day is all about celebrating equal rights, but it's important to note that when women first won the right to vote more than a century ago, equal rights weren't so equal.

The basics of Women's Equality Day are easy enough to understand: we celebrate it because on August 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment was certified, making it illegal to deny citizens the right to vote based on sex.

Here's what you might not know: the blanket use of the word "women" when discussing what the 19th Amendment changed is misleading.

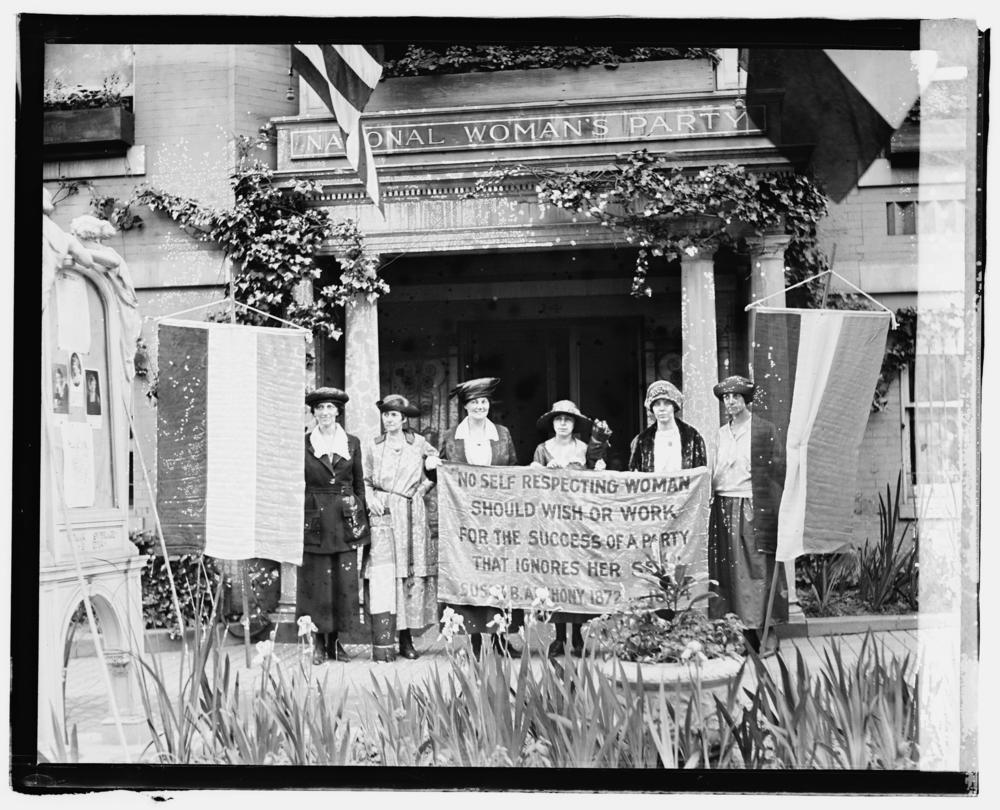

Millions of women — those who weren't white — were effectively left out when it came to gaining the right to vote in 1920, despite Black women's involvement in the suffragette movement. Some white suffragettes also viewed it as a great injustice that they did not have the right to vote, even though Black men legally did. What appeared to be a fight for equality on the surface had more than a few racist caveats tacked on, creating a stark contradiction in what suffragettes like Susan B. Anthony were arguing was morally right.

"This history should be a reminder to all of us that selective equality that only affords benefits to a privileged few is simply another form of inequality in disguise," Jocelyn Frye, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, told NPR. "Thus, it is critical to have an accurate understanding of the history being commemorated by Women's Equality Day – so that while we celebrate the progress achieved, we also recognize the inadequacy of this progress, especially for women of color."

Does that mean it's problematic to observe Women's Equality Day? Speaking to numerous women of color who are voting rights advocates, the answer isn't a simple yes or no. In fact, the question itself might be the wrong one altogether.

First things first: know your history and accept that nothing is simple

While gaining the right to vote for white women was a journey that ended in the fall of 1920, it would take other disenfranchised groups decades longer to gain equal access to the polls. Black women were largely prevented from voting due to individual state laws, harassment and violence, and other racist barriers designed to control which groups had political power.

The 24th Amendment in 1962 helped to chip away at voting equality by barring states from tying the right to vote to poll taxes, but many people of color did not fully gain the legal right to vote until the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which outright barred racial discrimination at the polls. For example, Black men were legally allowed to vote due to the passing of the 15th Amendment in 1870, but they faced an extremely difficult time actually exercising that right in practice.

But even the Voting Rights Act wasn't full-proof protection for marginalized communities: the 1975 extension of the Voting Rights Act was a huge factor in combating discrimination based on language, which had played a role for decades in the Latinx community being able to exercise their right to vote.

Similar language-based tactics were used against Asian Americans, who had to fight a hard road to first gain citizenship and then vote, Asian Americans Advancing Justice explained in a 2015 report. And although Native Americans got the right to vote in 1924 with the Indian Citizenship Act, several states continued to bar them from voting; they continued to be kept away from the polls for decades. Even today, Native American communities struggle with access due to loopholes involving voting ID laws, according to a 2019 report from the Brennan Center For Justice.

Recognizing the imbalance

So what does this day mean for every group who was left out of the 1920 victory?

It's possible to acknowledge that the 19th Amendment was an important step towards gaining equal voting rights while still acknowledging that what many suffragettes was fighting for wasn't truly fair, Tiana Epps-Johnson, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Tech and Civic Life, explained.

"As a woman of color, I get to hold multiple things at once being true," she said. "There were deliberate choices to exalt the rights of white women in particular in this effort at the expense of the rights of Black women, and that is a part of the history of women's rights that we don't really sit with."

"Like a lot of my work in democracy, I'm really fueled by that gap between the stories that we tell ourselves about what is at the heart of our democracy ... about it being for everybody, and the gap that exists in practice between that," she continued. "And I see that there continues to be these gaps today between the democracy of our ideals and that democracy in practice."

Kat Calvin, founder of the nonprofit Spread The Vote, had a similar view: that we can acknowledge an important moment, if for no other reason than that it played a vital role in reaching a later victory.

"It's not practically true [that all women were able to vote after the 19th Amendment], but it's still a thing we should celebrate," Calvin said. "And we, as Black women, would not have been able to win the right to vote, you know, practically ... if that amendment hadn't passed, so it was a really important moment and an important step for us to be able to get where we needed to go."

For Frye, it's all about the opportunity to learn and to push forward toward change using the knowledge that we can glean from our nation's complicated history.

"For me, Women's Equality Day is really an opportunity to remind people that equality in words is not the same as equality in practice," she explained, adding that the history of the holiday can be a valuable teaching moment. "The racism that fueled women of color effectively being excluded from the protections of the 19th amendment is the same racism fueling today's voter suppression efforts. These connections become clearer when we take the time to look beneath the historical rhetoric and, instead, create an accurate historical narrative that can inform our present-day actions."

Focus on what you can do today, advocates say.

The fight for voting equality didn't end on August 26, 1920, or even on August 6, 1965, when the Voting Rights Act was made law. It's not over today, either, advocates agree.

"To view voting equality as a thing of the past is to deny ongoing efforts to gerrymander districts that prevent marginalized communities from fully being able to exercise their opportunity to elect the candidate of their choice," Elizabeth OuYang, a civil rights attorney, adjunct professor and voting rights advocate, told NPR.

"[It's to ignore] the Supreme Court finding section four of the voting rights unconstitutional," she continued, referring to a series of Supreme Court decisions that have left Americans, in 2021, without many of the protections that the Voting Rights Act was intended to provide.

The fight for equal voting rights is very much in progress and it's being fought in local election offices, in voting registration drives, in protests and in rallies. And there are things you can do to get involved. Epps-Johnson stressed how essential volunteer poll workers are. OuYang suggested taking action beyond just casting your vote — learn about and get involved in redistricting, which happens every 10 years and has a powerful effect on all future elections, she said.

"Being informed and being educated is the first step," OuYang said.

For Calvin, the impact that any one individual can have can't be stressed enough.

"We're in a place now where Congress isn't going to save us. ... It's up to us to look around our family or friends or our neighborhood and say, 'All right, I'm going to make sure that 100 percent of the people in my family vote. What do I have to do to do that?'"

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.