Section Branding

Header Content

COVID-19 Delayed Quinceañera Celebrations. And Now, 17 Is The New 15

Primary Content

Citlaly Olvera takes a deep breath as she absorbs the scene in front of her at a rented Jewish temple in Brooklyn: Under the neon blue lights, a sea of family and friends, in gala gowns, suits and tuxes, cowboy hats and boots, are laughing and dancing to ranchera music so loud you can feel your rib cage vibrate.

She, herself, looks like a fairytale princess in her cream-colored, hooped dress, her translucent sparkling nails and, of course, her tiara.

They are all here for her, to celebrate her quinceañera. It's a traditional Latino ceremony for 15-year-olds to mark their transition from girlhood to womanhood.

In a moment, she'll be accompanied to the stage by about half a dozen chambelanes, the young men chosen to escort the birthday girl for the formal start of the evening.

In all the fanfare surrounding her quinceañera, there's just one little glitch: Citlaly isn't 15. She's 17. And there are plenty of girls just like her across the country.

The pandemic delayed many traditions and ceremonies. Weddings, birthdays even memorial services were put on hold, some for more than a year, while communities endured lockdowns and economic instability.

As more people have gotten vaccinated, however, events like these are coming back. That's meant a huge demand for event planners like Marcos Ortiz, in Brooklyn, who worked with Citlaly and her family to make her long-delayed celebration happen.

"It's really crazy," Ortiz says. "We're doing five or six events per day on the weekend."

With everything coming back a the same time, he says there's a huge backlog, with some people who have been on his wait list for more than a year. In fact, the wait for her party was so long, Citlaly almost gave up.

Almost.

A self-described "tough cookie," Citlaly was raised by her mom, Miriam, and her grandfather, Antonio Salazar. He was a tough cookie himself, she and her mother say. He used to be a boxer in Mexico City.

"He was so very strict, and somewhat sexist," Citlaly's mom, Miriam, remembers. "But he turned soft with his grandchildren. With time he turned into a feminist."

In fact, he showed Citlaly how to defend herself if a man ever tried to hurt her.

"He's the one that taught me that my left is always my domain," Citlaly says holding up a small fist with a mischievous smile. "So he was like 'you a lefty, so punch 'em with your left.' "

Citlaly's father died when she was a little girl, and she viewed her grandfather as a dad. She says on weekends, when the family would get together, the two of them would plan her quince — what she would wear, what kind of music there would be.

He wanted Mariachi —a strolling Mexican band— to accompany a procession to the church service, where they honored family members and prayed, before the party. Each detail of the tradition was important to him.

"I would be like, 'Are you ready? Are you ready?' " Citlaly says. 'We're gonna dance all night.' And he was like, 'Yeah, we are.' And then one day my mom was like, 'He's gone.' " Her voice trails off and she looks away.

Family loss and a pandemic's toll nearly prove to be too much

It's still hard for the family to speak about the losses they endured in the last year.

Don Salazar died in April 2020, of cancer, days before the planned party. And just a few months before her July birthday. She was devastated by his death. So she postponed her quince.

"I said, 'I don't want to do this no more. My papa isn't here no more,' " she says, looking away again.

Citlaly says she used to be someone who showed a lot of emotion, but in the last year or so, she learned not to wear her heart on her sleeve so much.

The postponement became weeks, months, then indefinite. In April 2020, New York was just emerging from a massive lockdown because of COVID-19. The city had been a veritable ghost town.

Miriam, who cleans houses for a living, had lost most of her income. Still, Citlaly says her mom tried to encourage her.

"My mom, she's in my room so many times and said, 'You got this, you got to keep your head up.' "

When things got back to normal, her mother said they could have the party. Her uncle stepped up and offered to take Antonio Salazar's place, as father and sponsor of the Quinceañera ceremony.

But things never really got back to normal, especially for many Latinos. The community has been hit hard by the pandemic: Nationally, Latinos had more than twice the death toll as whites. In New York, Latinos also lead in the mortality rates.

Citlaly's family was no exception. In the next few months, she lost the uncle who was supposed to replace her grandfather. Then her aunt. Followed by her godmother.

Two other family members were placed on respirators.

Citlaly turned 16. Then 17. She felt there was no point in doing a quinceañera.

Instead, she got a tattoo on her left ankle, in heavy, black bold font.

It reads: "They come, they go."

"People come and go," she says. "So I better not get attached. I better not feel like they're gonna be here forever, because they're gonna leave at some point."

Maybe a party will help the family heal

By 2021, vaccinations brought welcome change to New York. The city began opening up, and Miriam found work.

To be honest, Miriam says, neither she nor Citlaly was in the mood for a party. There had been too much loss. But the dancehall reservation was non-refundable. And the spirit of her father, Citlaly's grandfather, still lingered.

"When my husband died many years ago" Miriam says, "and I did not know how to carry on, it was my father who told me, 'You have to get up. For your children.' "

She says she suddenly felt a sense of defiance and announced, "We are going to do this ceremony."

Normally, quinceañeras are a celebration, says Ortiz, who also serves as MC at many events he plans. Because so many families experienced losses, he now has to find the right tone between remembrance and celebration.

"It's my responsibility to make the event fun, but also incorporate the loss," says Ortiz, who admits it sometimes can be difficult. "I come up with it in the moment, I feel what the customers feel. I've already had two quinceañeras who didn't have their father. I try and get in their shoes. I lost an uncle to COVID; he only lasted one week. I get it."

It was like that for Citlaly.

She had spent years with her grandfather planning this day. He had explained to her the importance of this day, on which she would become a young woman.

She and her mom go to his former house to get dressed. As the last curl is pinned on Citlaly's head and the last bit of her corset tightened, the Mariachi arrive, just as Antonio Olvera had wanted.

They begin playing in the hallway, ready to escort her to church and later the Jewish temple, where she'll complete the transition.

The spirit of her late grandfather helps her cope

At a table sits a porcelain doll, hand painted to resemble Citlaly. This is known as el último juguete — the last toy. It represents Citlaly's childhood, and it will be gifted to her tonight. She will then give it away — she's chosen her younger sister — and in exchange will get makeup. Citlaly and her sister will dance holding the doll, an important symbol of the transition into womanhood.

Waltzes also play a key role at a quinceañera, none more important than the one when a girl dances with her father, or grandfather.

A somberness falls over the venue; Citlaly breaks tradition. She picks up a photograph of them together, and heads to the dance floor.

"Nobody is ever gonna fill his spot," she says of her grandfather. "I want him to have his spot."

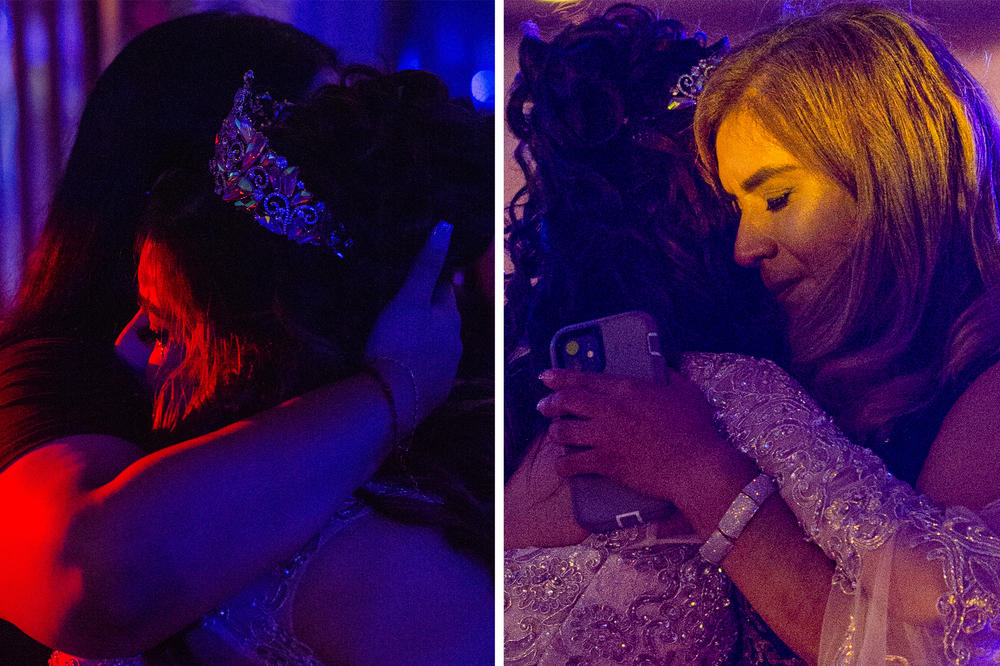

Holding the picture tightly, she twirls by herself, in a translucent halo of cream fabric. Her mother, Miriam watches.

"This is what I have tried to make of her," she says of her daughter's strength. "The dance has to continue. Even if on the inside you are sad, even if on the inside you are destroyed, the dance continues."

But even the toughest cookies crumble. As Citlaly waltzes alone, with the photograph, she starts to sob.

Her mom is quickly by her side. Holding her, and they start to dance.

They come and they go, Citlaly's tattoo says. Far too many of their family members have left.

But the two women who are still here waltz together, on a summer Saturday night, in Brooklyn.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.