Section Branding

Header Content

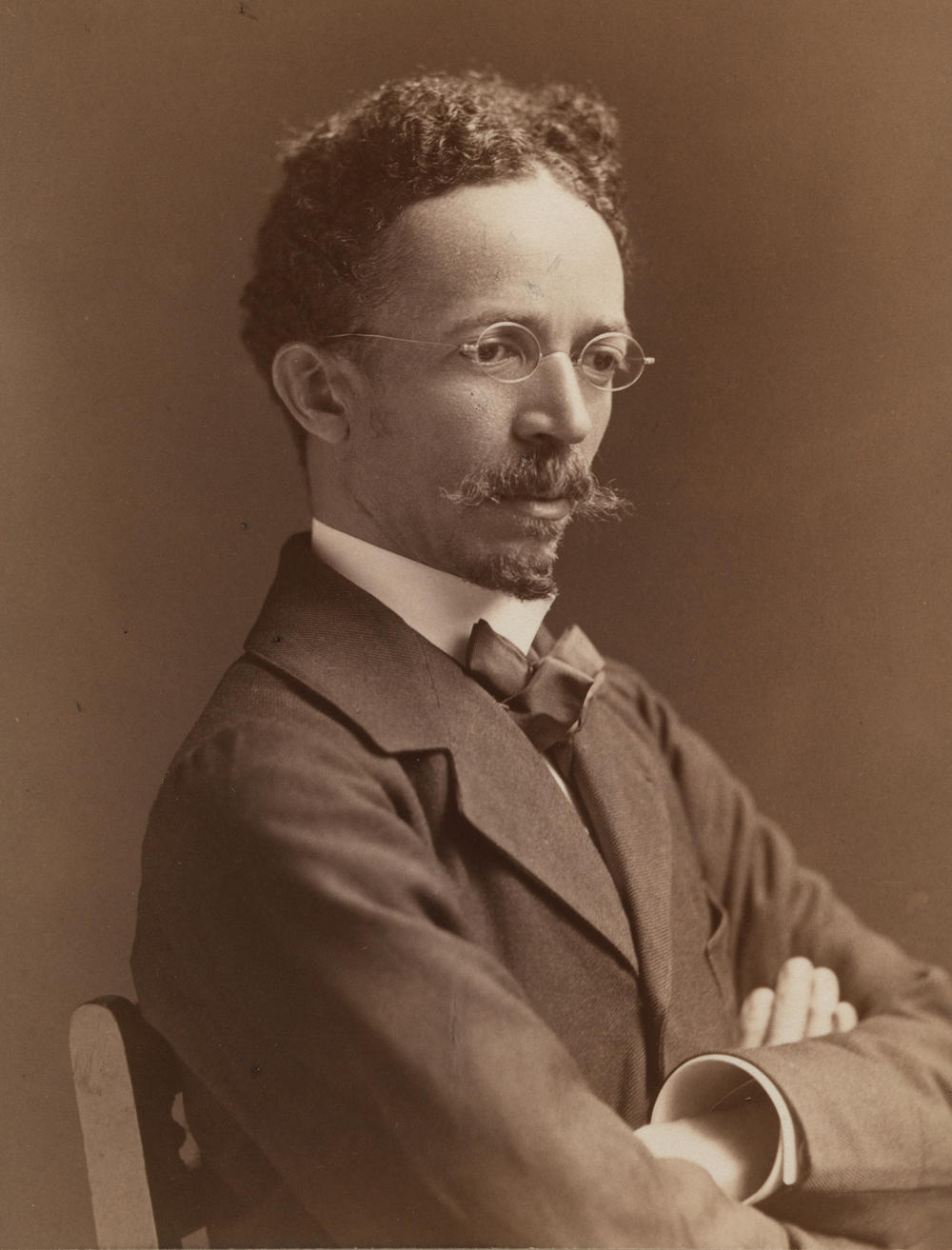

X-Rays And Infrared Reveal The Story Of The 1st Internationally Known Black Painter

Primary Content

I just met Henry Ossawa Tanner. Nice trick, since he died in 1937. Tanner was the first African American artist with an international reputation. His paintings are in many museums, but I've walked past them countless times. Now, preparing for this column, I got to know a bit about his life and times (as well as new revelations about his artistic thinking) and thought I'd make the introductions.

Quite the gentleman. Born in Pittsburgh, 1859. Grew up in Philadelphia. Died an expatriate in Paris. "He saw right away that he could do better in France," says Dallas Museum of Art curator Sue Canterbury.

He was having trouble getting into the art classes he wanted — and finding teachers who'd take him on. In France, skin color didn't matter as much. He told a magazine writer, "in Paris no one regards me curiously. I am simply M[onsieur] Tanner, an American artist. Nobody knows or cares what was the complexion of my forebears."

The French liked his work. In 1897, the government bought one of his pieces for the state collections. With that rare honor his reputation soared. Museums started buying Tanners. By 1900, when mass reproductions of Christ's portrait and books on his life were circulating, curator Canterbury says, "Tanner was considered the leading European painter of religious scenes."

It's a lovely image, with what came to be called "Tanner blue" — a color that became his signature. Tanner's models were his wife, Jessie Olsson (Swedish American from San Francisco; she was studying opera when Tanner met her in Paris), and their son Jesse. Family influence is at the heart of Tanner's religious works. His father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal church. The family was highly educated, and Canterbury says their home was "a center of black cultural life," in Philadelphia.

Christ and his Mother Studying the Scriptures is one of two Tanners on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through early January. Conservation work was done on both, and X-rays and infrared photography revealed surprises and insights into the artist's thought process.

"Conservation never gets old," says conservator Laura Hartman. "There's always an 'aha!' moment." In this one, when the painting was turned horizontally, x-rays showed another composition underneath. Two draped figures in a landscape. Aha! Nobody had seen them before. Tanner gave up on them, and turned to the Holy Family instead.

The other Tanner in Dallas (both paintings presented in conjunction with the Art Bridges Foundation) was done early in his career. Scholars call this a "genre" painting — a glimpse of ordinary daily life.

Religion plays a role in this piece, too. The old man reaches for the heavens with his praying hands. His prayer of thanks is so intense. The boy also concentrates, but I wonder if he doesn't fidget a little. See how the bench he sits on tilts forward?

Hartman's discoveries here show Tanner working on composition.

He moved plates and postures around to highlight the old man's hands. Once conservator Hartman removed the darkened coat of varnish, she revealed Tanner's use of many colors — bright blues, oranges, layered, scraped, sanded and textured.

When he was 11 years old, Henry Ossawa Tanner spotted a man painting in a Philadelphia park. The boy decided he wanted to paint, too. His parents gave him 15 cents, and he bought — his words — "dry colors and a couple of scraggy brushes." Eventually he became well known and an inspiration. Working in his Paris studio, he was a role model for other painters.

Canterbury says "any African American artist who went to Europe had to make a pilgrimage to see Tanner." They saw an artist succeeding in spite of prejudice, who encouraged and helped them with advice, even money. Those first 15 cents ended up becoming a very good investment.

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing online offerings at museums you may not be able to visit.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Correction

A previous version of this story misidentified the curator at the Dallas Museum of Art. Her name is Sue Canterbury, not Cunningham.