Section Branding

Header Content

There's A Shortage Of Home Health Aides For The Elderly, And It's Getting Worse

Primary Content

Many Americans hope to spend their old age at home, rather than moving into a care facility. When the time comes, they rely on the more than 2 million home health aides who provide day-to-day support.

But there are about 54 million Americans age 65 and older, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and that number is expected to rise to 95 million by 2060, making it increasingly difficult to get help. And as baby boomers age, the demand is expected to be much higher.

In fact, there are more projected job openings for home health aides in the next decade than for any other occupation. One study estimates that 70% of adults age 65 and older are expected to need some form of basic assistance. The demand and supply is very imbalanced.

Kezia Scales is the director of Policy Research at PHI, a national nonprofit organization that advocates for home health aides. She says these jobs are exhausting, with low wages, little respect and almost no career growth.

"And so we end up having a fairly unstable workforce with high levels of turnover and job vacancies, not because people don't want to do this work, but because they can't afford to do this work," she says.

These jobs have traditionally been "invisible and undervalued," Scales says, because the vast majority of aides are women, people of color, and immigrants.

For years, advocates like Scales have been calling for changes in training, wages and supports for home health aides.

"We don't need tweaks to the system, we need a complete transformation," she says.

Now, a proposed $400 billion infusion of federal money into the nation's "care economy" over eight years, could do just that. Though there aren't a lot of details available, it appears the bill would expand access to home or community based care for seniors and people with disabilities, extend a Medicare program that helps move elderly residents out of nursing homes and into their own homes or homes of their loved ones, and improve wages and benefits, working conditions and training for home health aides.

A successful model trains and employs home health aides

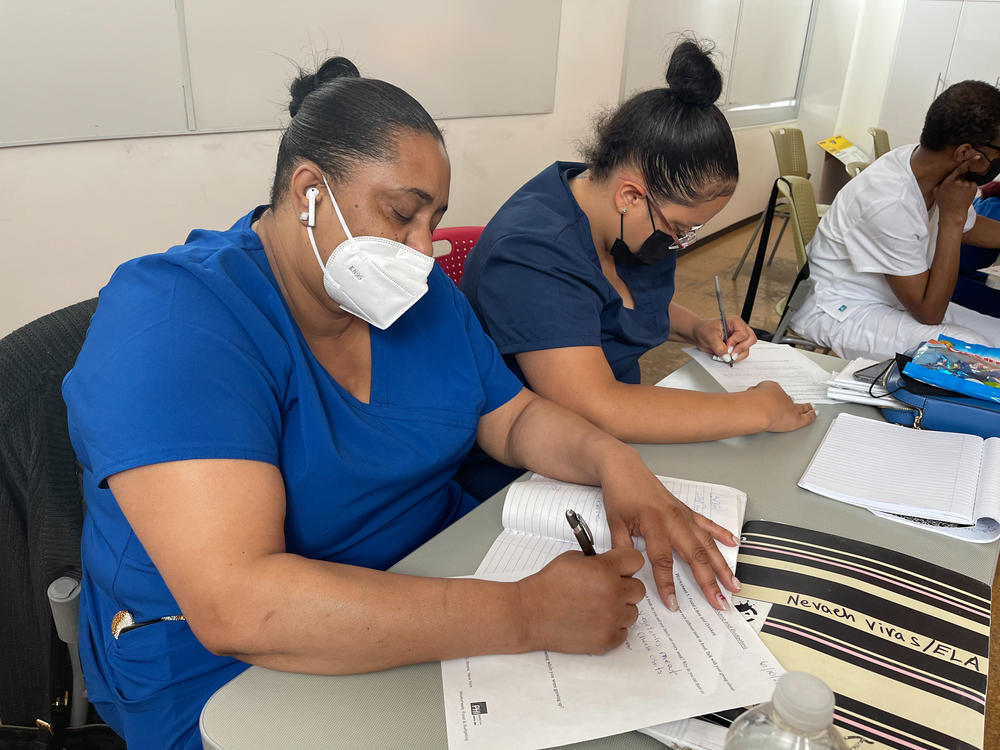

Scales points to Cooperative Home Care Associates as an example of a successful model that trains and then employs home health aides. It's funded with a mix government and private money, including from PHI.

Tashawna Vivas is one of the students. During a lesson this summer in "Bed-bath," the 49-year-old practices washing a classmate's foot. Instructor Andria Sharper reminds her to make sure the skin is completely dry.

"In between the toes is very important right? Specially [for] diabetic clients," Sharper says.

Vivas looks proud of herself. "My back is a little busted but it'll be OK!"

Vivas will also learn how to safely turn someone to prevent bedsores, what a normal blood pressure reading is, and when changes in urine color might indicate a health problem.

The work deserves a higher wage but Medicaid reimbursements lag

The four-week full-time training course is free, which is unusual. Matt Sigelman, CEO of the job market analytics company Emsi Burning Glass, says the median wage for a home health aide is $24,000 a year.

"For perspective, that's only about $500 more per year than your average fast food cook. So the notion of taking out a loan [and] going into debt, to get into a job that pays you the same as you would make in a fast food restaurant is pretty hard to swallow."

Cooperative Home Care Associates also provides benefits. But even here, aides make only minimum wage. CEO Adria Powell says that's because reimbursement rates from Medicaid and Medicare are so low. "The work is deserving of a higher wage, we are unable to do that because of the reimbursement structure," she says.

Paul Osterman, author of the book, Who Will Care for Us? says home health aides are very restricted in what they can do for their clients. For example, they can only remind a client to take their medication, they can't actually give it to them.

Osterman argues for better training and expanded duties for home health aides, which he believes will help clients better manage chronic conditions and stay out of hospital.

"That would also save money and to some extent, take over some of the work from much higher paid nurses. So that would then create savings, which could then be used in part to pay for the higher wages," he says.

Cooperative Home Care Associates has career counselors who help mentor students if they want to study further and move up the career ladder with higher paying jobs such as certified nursing assistant (CNA) or licensed practical nurse (LPN). Tashawna Vivas hopes to be a nursing assistant one day.

"I enjoy helping people, taking care of people, 'cause I'm going to need somebody need to take care of me, too!" Vivas says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.