Section Branding

Header Content

The Debt Limit And The Senate's Cloture Share A History. Both Were Born With A War

Primary Content

The federal fiscal year ends this week, and once again Congress is scrambling to get its act together. And as the prospect of government shutdown looms, so does the wilder prospect of the government running out of cash and defaulting on its debt.

As always, political differences and partisan wars make the money process difficult. But two key elements of procedure also feature in the showdown, raising the stakes and defining the battlefield.

One is the debt limit. The other are the Senate rules that allow the minority party to stop legislation cold.

The two are intertwined at this moment because the debt limit, suspended three times during the Trump administration, has passed its latest suspension date. The Treasury Department has for weeks been using "extraordinary measures" to cover the checks it writes and also honor bonds that come due.

Without a green light from Congress to borrow more money, the Treasury will be unable to continue this stopgap accounting next month. That means checks you might be expecting from the government would bounce, and the U.S. would be in default on its obligations for the first time in its history. The financial consequences, both short term and long, could be severe.

And getting that done in the usual fashion has been thrown into question with Republican threats to filibuster the debt limit suspension Democrats are seeking in the Senate.

Curiously, both these potentially crucial elements became ensconced in congressional practice in a single year a century ago — a year that changed the country in many ways.

Cloture's origin story

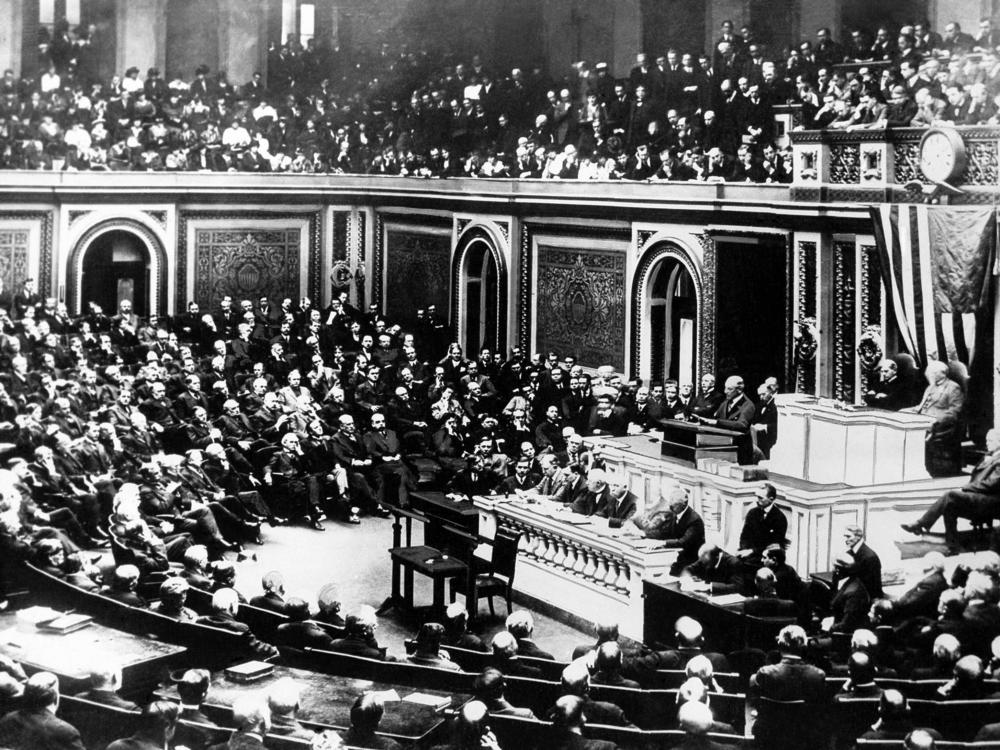

In 1917, the country was confronting momentous issues of war, conscription, Prohibition and votes for women — all at once. But the premier preoccupation was with war.

The year began with Germany escalating to unrestricted submarine warfare against U.S. shipping to Great Britain. Congress moved to arm merchant ships against these attacks, but the bill died in the Senate after a filibuster by a dozen senators who saw it as a backdoor U.S. entry into the war. They blocked a vote in the waning days of a congressional session, and the bill died when the session ended.

At the time, there was no procedure for cutting off such an "extended debate," which had been a senator's right since the early 1800s. The weapon existed but was rarely used, reserved for paramount issues such as creating a national bank or limiting slavery.

Arming the merchant ships seemed to be just such an issue to the filibustering group whom President Woodrow Wilson immediately condemned as "a little band of willful men." Wilson called a special session — and a manifesto supporting his bill and denouncing the anti-war senators was signed by 75 senators.

On top of that, the Senate adopted a rule that established cloture for the first time, allowing a supermajority to cut off debate and force a vote. The rule was adopted after six hours of debate, by a vote of 76 to 3.

War fever brought more change

That lopsided vote expressed the war fever gripping much of the country in March 1917. Most Americans had been opposed to involvement in the war that convulsed Europe beginning in 1914. Wilson had campaigned in 1916 on the slogan: "He Kept Us Out of War."

Now, Wilson was not only for arming merchant vessels, he also was moving toward an outright declaration of war. One big reason was a telegram that had been disclosed purporting to reveal a German plot to get Mexico to make war on the United States. The reward for Mexico was supposed to have been the return of the territory that had become Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

This so-called Zimmermann Telegram did not transform American attitudes as violently as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor would in 1941 and the terror attacks of Sept. 11 would again in 2001. But it moved the country and it moved the Congress.

Wilson got his declaration of war in April 1917. Congress began considering a draft to bulk up the peacetime Army and a $4 billion appropriation to bolster all the armed services as quickly as possible. Congress passed the War Revenue Act, raising income and corporation taxes, a new tax on inheritances and an "excess profits" tax and higher taxes on tobacco and a host of "amusements" and other luxury items.

But tax money comes in gradually, and much more money was needed right away. In the month Congress declared war, it also passed the First Liberty Bond Act to provide the initial billions in financing. In September, it passed a second such act, this time including a limit on the overall indebtedness of the U.S. at $15 billion.

The idea was to make the debt more palatable by keeping a lid on it, at least theoretically. Congress added the debt limit by statute. It is not a constitutional amendment. That means it could be altered or done away with at any time by the passage of another statute. And indeed, that original limit would have to be raised in the course of the war, which eventually involved more than $20 billion in five bond issues before and after the fighting ended.

This can also be seen as a nod to fiscal conservatives at the time and to those elements of the nation's population either opposed to the war or ambivalent at best. Americans with German backgrounds were distressed and in many cases persecuted, and many Americans with Irish heritage were incensed by Great Britain's suppression of Ireland's bid for independence in the Easter Rising of 1916.

The debt limit has often been circumvented but never abolished

The debt limit language also acted to ease the process of issuing new debt, which had previously been done through short-term instruments that were neither efficient nor sufficient for the fiscal task of a modern war.

As longtime Congress scholars Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein wrote in 2012: "The drive to enable Congress to issue longer-term debt instruments, even for specific appropriations, both lowered interest costs and made the borrowing easier for the Treasury Department."

Mann and Ornstein noted that the limit had long since become "vestigial," especially after Congress consolidated federal borrowing in the late 1930s, anticipating the arrival of World War II.

For most of the 20th century, Congress simply raised the debt limit to whatever was needed to accommodate the budgets already enacted. From 1979 to 1994, this was accomplished in the adoption of the annual budget resolution. It should surprise no one that the limit has been raised or suspended nearly 100 times since its creation, more than 80 times between 1960 and 2017 and three times during the presidency of Donald Trump, with Republicans in control of the Senate. U.S. debt grew by $7 trillion in the Trump years.

There have been problems from time to time, particularly when Democratic presidents sought to raise or suspend the limit when annual budget deficits were rising. Republicans in the House dug in on this battleground in 2011 under President Barack Obama, insisting he make deep cuts in federal spending. A deal was negotiated, but the specter of default haunted Washington for some while thereafter.

"Defaulting on these obligations would raise the cost of borrowing for the government, severely impact the U.S. economy and likely create upheaval in the world's financial markets," wrote Richard A. Arenberg in his textbook titled Congressional Procedure, adding that the "near miss" in 2011 led to a downgrade in the nation's credit rating by Standard & Poor's, which derided "political brinksmanship."

As the debt limit is statutory, it could be eliminated just the way it has so often been raised or suspended. But such a vote has not happened, perhaps because politically speaking it has seemed even riskier than voting to raise or suspend it.

Cloture has also become a fixture — and has shaped Senate behavior

The threshold for cloture was initially set at two-thirds, the same required for a constitutional amendment. It was not as insuperable a barrier in that era as it would later become, as there was considerable crossover between the parties on certain issues. In that same year, for example, the Senate would muster two-thirds for the 18th Amendment (Prohibition) and come within one vote of doing the same for women's suffrage. (Votes for women, the 19th Amendment, got through in 1919.)

In later generations, especially after World War II, the filibuster became closely associated with opposition to civil rights bills. Southern Democrats used it against anti-lynching laws and repeated attempts to break down segregation. It took the postwar civil rights movement and decades of effort to get two-thirds for the Civil Rights Act in 1964. The following year, the Voting Rights Act was passed without a filibuster. And 10 years later the Senate lowered the cloture requirement to three-fifths.

The requirement is still three-fifths, or 60 votes, in our time. But lowering the requirement only made the filibuster tactic seem less extreme. Allowing filibusters to be "virtual," with no all-night floor sessions needed, made it all the more attractive — a standard tool in a senator's toolbox. So, while a typical two-year Congress once had a handful of filibusters that required cloture votes, the majority leader now files cloture petitions on literally scores of measures every year.

That is why "it takes 60 votes in the Senate" has become a litany. And bringing over 10 members of the other party across the aisle on something important to their leadership is regarded as all but impossible.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.