Section Branding

Header Content

Vaccinated seniors navigate life in mostly unvaccinated rural America

Primary Content

Updated October 29, 2021 at 6:02 PM ET

For Marge Loennig, 87, the COVID-19 pandemic has stirred up many old memories. The most vivid is of a childhood friend who was stricken with polio.

Loennig remembers reading to her while she lay in an iron lung ventilator.

"Her arms and her lower body were all in the lung," she recalls. "It was very frightening for her and very frightening for us."

Back then, everyone seemed to know someone with the disease, and when the vaccine became available Loennig remembers people eagerly lining up to get it. Today, she believes COVID is still being downplayed, its deaths and illnesses underreported. Today the laws are also different and health officials are prevented from being as open about who is sick and who is dying from the virus.

"It has been a secret and so people have not feared it the way we feared polio," she says. "I think that if people had been open, some of the anti-vaccine people would have not been so reluctant to get shots."

There is plenty of vaccine reluctance, if not outright outright defiance, in Loennig's hometown of Baker City, Ore., the historic first stop on the old Oregon Trail in the heart of the state's deeply rural and conservative eastern side.

Vaccinated rural seniors are living on an 'island'

Sitting on an antique chair in the living room of her historic Victorian home, the wall above her adorned with paintings and her 9-year-old granddaughter's art, Loennig says today her town is deeply divided and just like almost everywhere else, COVID is political.

It's the opposite of what she remembers as a little girl when families had to lock down often during polio. In the 1930s when she was 3, she also had to stay indoors for three months after contracting scarlet fever. Her father even had to temporarily move.

So taking precautions and living carefully throughout 2020 until the COVID vaccines became available was not a big deal, Loennig says. Back when she was a girl quarantines were strictly enforced by health authorities. For most people, it was a fact of life.

"They did not have this anger that just seems to overwhelm," Loennig says. "Somehow we have to get at the root of that anger if we are going to face — and we will face — future episodes of this kind."

For now, Baker City seniors like Loennig are kind of on an island, still moving cautiously, avoiding the unvaccinated as much as they can. Only about 45% of the 16,000 people in this county have gotten both shots.

But among the 70 and up demographic, it's 25 points higher.

This mirrors a trend across rural America where overall COVID vaccination rates continue to lag about 10% lower than in cities. Yet seniors in rural areas tend to be a holdout with vaccination rates higher than the national average. In towns like Baker City, many are eager to get their boosters as the shots become more widely available this week.

Still plenty of holdouts who won't get vaccinated

At a Baker City senior center, a cold rain is pounding down outside, steaming up the windows as dozens of folks line up for the buffet lunch service.

Sipping tea, Danae Simonski, 84, says she recently learned that some of the ladies in her card group aren't vaccinated. She has a pacemaker and tries to be as careful as she can.

"Well I'm not playing Bridge anymore," she says, chuckling.

Simonski says misinformation about the shots is swirling around Baker City.

"I heard someone say they're not getting it 'cause it has formaldehyde and anti-freeze in it," she says. "I mean, people can believe what they want to believe, but they have to learn to pay the consequences, that's how I feel."

A few tables over, a 73-year-old man introduces himself as Bob Brown. He is unvaccinated and doesn't sound too worried about those consequences, even with an immuno-compromised wife at home who is still suffering the effects of long COVID.

"There's almost nothing that could convince me," he says. "And most of the people I know that don't want to take it, they have the same feelings, they don't trust the government."

Brown is wearing a MAGA hat with a National Rifle Association patch attached that looks like it's had some miles. He says Democratic politicians used to mock the so-called Trump vaccine and Operation Warp Speed, and now he says they're claiming "you're evil if you don't take it."

He and some friends at the table are also comparing this current moment to polio, albeit through a far different lens.

"We took the shot, it actually worked. This thing here that they're giving ya I don't think does," he says.

The COVID vaccines being used in the U.S. range from 71 to 93% effective.

Still, nationally, polls have shown hard-line conservatives tend to be less vaccinated. Baker County voted 74% for Donald Trump.

Public health officials were encouraged to see vaccination numbers start to tick up some during the recent delta surge. At times, the small local hospital wasn't able to transfer its patients to the nearby Boise area because hospitals there were full. Still, local health leaders aren't sure what more they can do to convince the remaining holdouts to get the shots at this point.

"We have a constant challenge with misinformation," says Nancy Staten, the administrator of the Baker County Health Department. "So we just continue to stay the course and put the best information out there that's available to help people make their best decision."

Today is a far different time than during polio

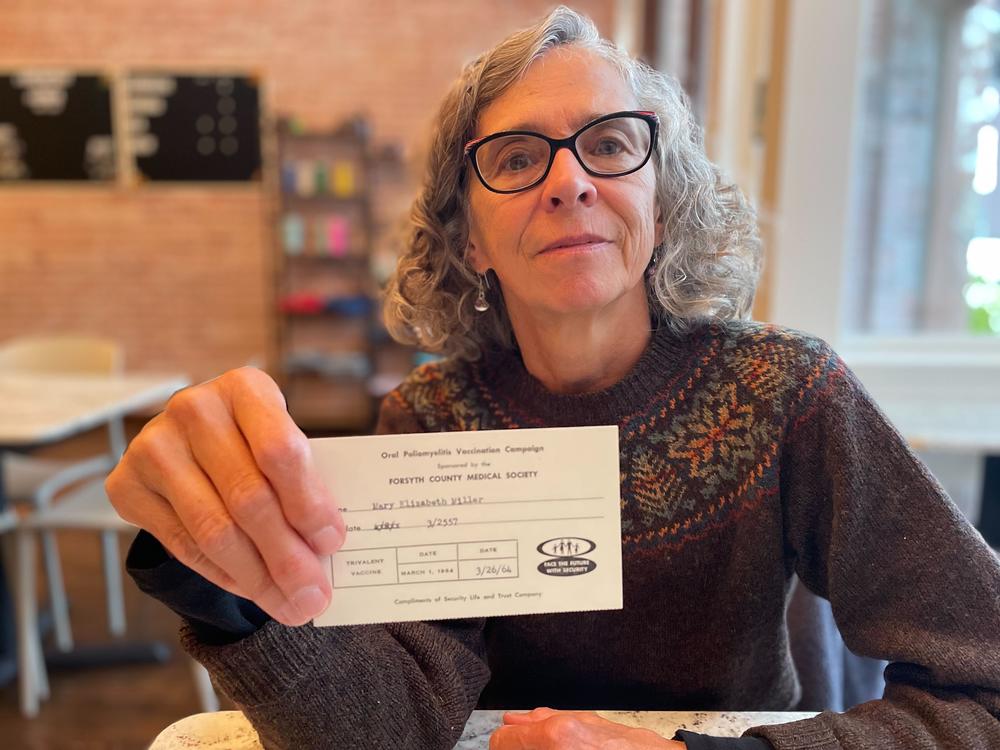

At Sweet Wife Baking, a cafe in downtown Baker City, Mary Miller is holding her polio vaccination card from 1964. Miller is a retired nurse who now works down the street at a wine store. She says she recently all but gave up trying to talk to her neighbors about why they should get the COVID vaccine.

"I have really had to work on this not causing me to lose my faith in people," Miller says.

At 64, Miller is eager to get a booster shot. She recently began to travel again, including a visit back home to see her 91-year-old mother in North Carolina after missing her planned milestone birthday last year.

Fellow regular Randy Tracy and his wife Joanie are also traveling again, some, though they still take the same precautions they did before they were vaccinated. They seek out accommodations with keypad remote entry and have only flown once since being vaccinated.

"I would like to get back to life altogether but I think we're still in a process of waiting this out," Joanie says.

She's waiting to return to volunteering at a local nursery until she's gotten her planned Moderna booster. Her husband Randy, a 72-year-old Marine veteran, sees today as a very different time than polio, when the country had gone through a Depression and World War II. Back then, he says, it felt like there was a greater sense of helping your neighbor.

"It wasn't necessarily about God and country and patriotism, it was you didn't want to let the guy standing next to you down," he says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.