Section Branding

Header Content

They ran the 1st New York City Marathon. Only one returns for the 50th

Primary Content

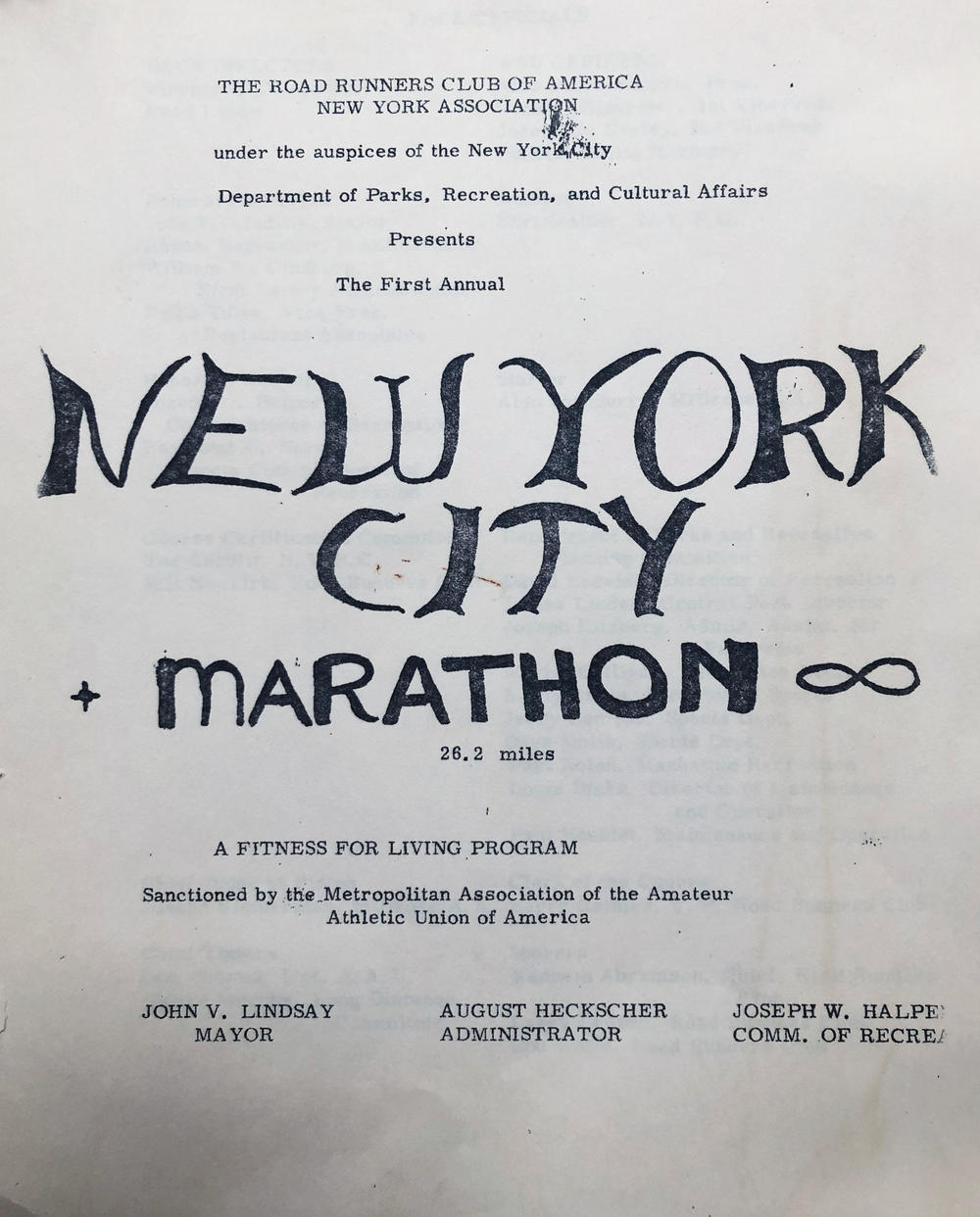

In 1970, on a hot September morning, 127 running enthusiasts safety-pinned paper numbers to their shirts and took off on the inaugural running of the New York City Marathon. The course featured four loops of Central Park, a single water stop, and cost $1 to enter. Only 55 finished, all men.

This year, only one of the original finishers will be competing in the marathon's 50th running. It will be his first glimpse of the race that now winds through all five boroughs of New York City.

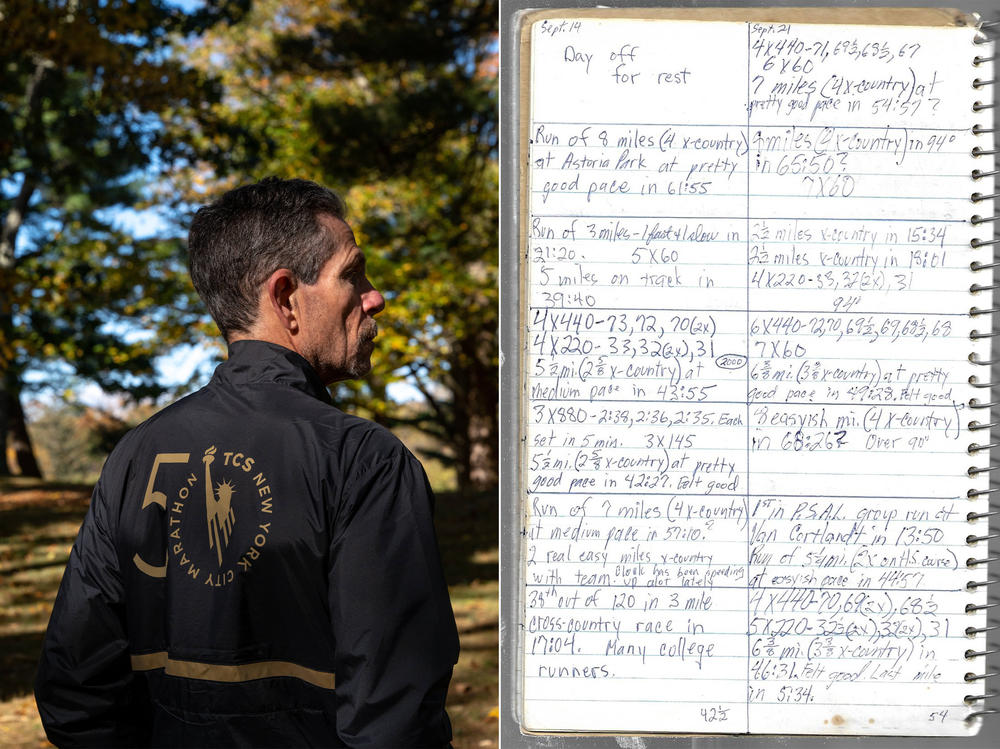

"This is one of my first endeavors as a retired person," says Larry Trachtenberg, 67, a former special ed teacher originally from Queens, N.Y., who has been training three times a week at home on the west coast.

Trachtenberg says he's surprised that he is the lone athlete to run the first and the 50th version of the race.

There should have been another: Jim Isenberg

Isenberg, now 70, would love nothing more than to lace up his shoes on Nov. 7. He placed 25th in the original race. He didn't know Trachtenberg back then, but their lives eventually intersected in several ways. They both ran at Princeton. They both became educators. And they both settled in Eugene, Ore., where they frequently discussed running New York City's 50th anniversary race.

But in December 2017 everything changed, and there was no chance the Boston native would run this year's New York race – or any other.

Strangers in a strange race

In 1970, Isenberg was a 19-year-old sophomore at Princeton. He had already run four marathons – including Boston twice – when the university's new cross-country coach, Larry Ellis, told him about a new race in New York City.

All Isenberg knew about the city, he said, was "that the 'damn Yankees' played up there," and that he wouldn't have to deal with Jock Semple, the race official who tore up Isenberg's original birth certificate and tried to disqualify him after his 26.2-mile debut at the 1969 Boston Marathon. (Semple didn't believe he was 18, the minimum age, and shredded the proof, calling it "Phony, phony!" Two years earlier, Semple tried to rip the race number off Kathrine Switzer mid-race, for being female.)

To please his coach, Isenberg took a $1.80 bus ride to Port Authority, found his way to the start, and lined up wearing bib 64.

Elsewhere in the field stood 16-year-old Trachtenberg. He hadn't consulted anyone. He didn't know how to train. He was fast, but his longest competitive effort was two-and-a-half miles, the standard high school cross-country distance. He had never run a road race, and had spent the summer working for tips at a ritzy summer camp, dashing back and forth to the highway to stay in shape. But he was up for a challenge on the day before he started 12th grade.

Heat decimated the field, attrition set in, and by the third loop, Isenberg said he was ready to jump in a pond and drink half of it. He finished in 3 hours, 18 minutes, 19 seconds.

Trachtenberg, intent on staying in his comfort zone, finished nearly four minutes later in 32nd place.

"My game plan worked perfectly," he said.

And that was it. One and done for Trachtenberg. No camera, no photos.

"I didn't think it was going to turn into anything," Trachtenberg said last week.

Running into each other at Princeton

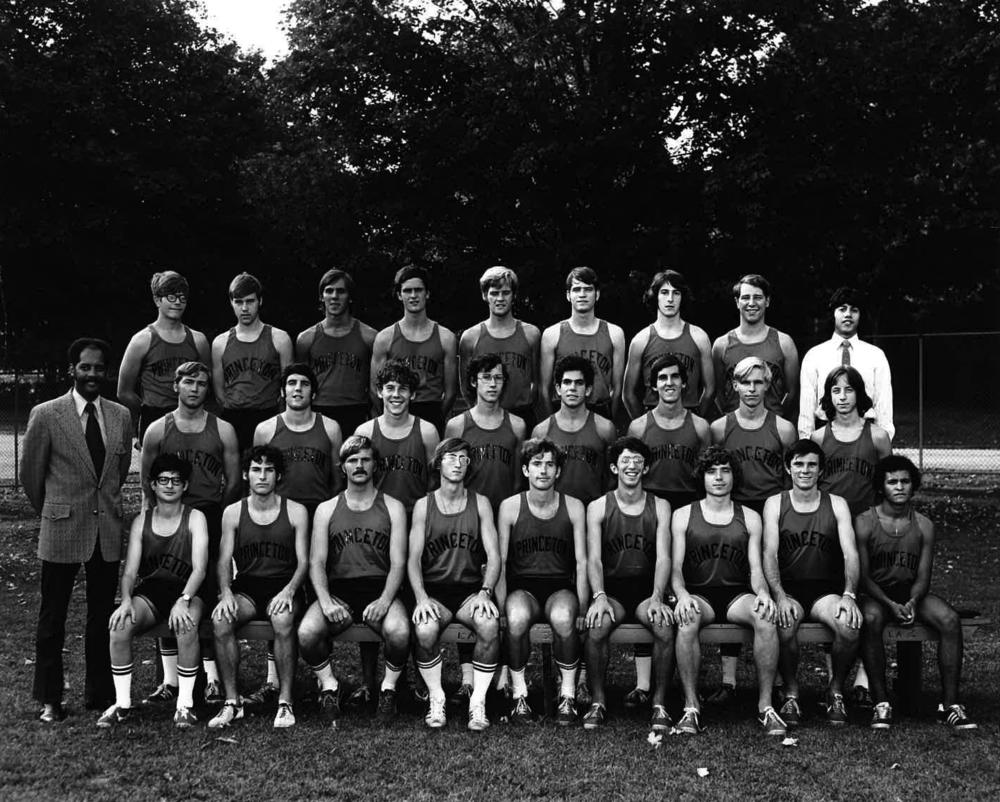

A year later, the two met at Princeton as cross-country teammates where they figured out that they were both in that inaugural race.

Isenberg continued to run marathons on the side. He graduated in 1973, earned a PhD in physics, and became a renowned math professor and physicist at the University of Oregon.

Back at Princeton, Trachtenberg qualified for three NCAA national championships under Coach Larry Ellis, the first Black head coach in the Ivy League. After graduating in 1976, Trachtenberg became a teacher, specializing in vocational skills for special ed students in the public school system.

Coincidentally, their careers brought both men to Eugene, Ore., also known as "Track Town USA."

The road to Oregon

Trachtenberg came first, in 1978, straight out of graduate school at the University of Tennessee.

Isenberg arrived in 1982 to teach college math. He continued to run marathons – including four New Yorks (most recently in 1989) and 30 Bostons. The 5-foot-3 academic also became a self-described memorabilia hoarder, collecting race shirts, trophies, uniforms, numbers – even the bottom half of the entry form from his New York City debut. The collection remains on his 18-acre farm north of Eugene, along with 10 goats, 12 sheep, 18 chickens and a llama to guard the livestock.

Isenberg ran that farm for 25 years. The neighbors run it now.

The accident

On Dec. 18, 2017, Isenberg was on a work trip in Sydney, Australia. After a 15-mile run to train for Boston, he went to Bondi beach with his wife, Pauline, and two nieces. When the nieces went into the water, he waded in to supervise them. Out of nowhere, a wave struck and flipped him facedown. He broke the C2 and C3 vertebrae in his neck and stopped breathing.

Back in Eugene, Trachtenberg heard the news via email from a man in the local running group who had been in touch with Isenberg's wife.

"It sounded extremely bad," Trachtenberg recalls. "But I still remember one word in there, the word 'partial,' like a partial severing, giving me just a little bit of hope. But he was in severe shape. Like, let's hope he survives, because there were other issues."

The prognosis was not good. Doctors told Isenberg's wife, "You should probably let this guy go," says Isenberg, who remembers neither the accident nor the next five days.

"But she was pretty persistent," he adds. "I owe a huge amount to her."

But the paralysis was permanent. After 143 marathons, Isenberg, 70, is quadriplegic. He feels nothing below about three inches underneath his collarbone. He relies on a ventilator 20 hours a day. He uses a diaphragmatic pace setter (DPS) speaking device during the other four. Four or five times a week, he is hooked up to electrodes and rides a "stim bike" for 80 minutes. He lives in a retrofitted house eight miles outside of Washington, D.C. He's still actively publishing papers, researching math, and editing journals.

He has also been giving marathon advice to Trachtenberg, as his old college teammate prepares to run his first marathon in 43 years.

Isenberg ran several Bostons in his 60s, after double knee replacement.

"So I talked to him a number of times and emailed him about how to prep for the race as an old person," Trachtenberg says.

During the race, the veteran marathoner recommended that he take walk breaks and, as much as possible, save the walk breaks for the downhill sections to reduce the pounding on his thighs.

Also to reduce impact, Trachtenberg has mostly trained on soft, bark-covered paths, logging about 26 miles a week, divided among three days. On Oct. 20, he took his longest run, 14 miles – on pavement, to get accustomed to the pounding.

"I have various ailments," Trachtenberg says, including osteoarthritis and a narrowed and calcified heart valve. He says he has been medically cleared to compete but it means he has to compromise. "I have to get in as good a shape as I can, knowing it's not really what I should be doing."

If all goes as expected, this Sunday he will line up at 11:20 a.m., in the fourth wave of starters based on his projected finish time of four hours, 26 minutes – his "best-guess estimate" – as one of the regular Joes who paid $295 to enter the race.

Trachtenberg admits he's a bit nervous.

"It's not typical for me to announce that I'm doing something," he says. "Now I feel like people are going to be watching me, tracking me on the website. So it's this little added pressure. It's funny how this thing kind of snowballed.

"Originally, I didn't know how my legs and body would respond. I had this knee thing, too. A bone fragment broke off my femur two years ago. I thought maybe if one piece of bone broke off and I started running again, more pieces of bone would break off, so I didn't want to do much running. I gradually increased it.

Trachtenberg says initially he was focused on being allowed in the race "so I could line up on the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and have that thrill. Like, maybe run over the bridge, and that would be it.

"As the training got better, I thought, 'OK, now my goal is to make it to Long Island City, Mile 15 [near the housing project where he grew up]. I feel extremely confident that I'll make it that far. Then it's kind of up in the air between mile 15 and mile 26."

If there is discomfort in his chest, he will stop.

After his echocardiogram in September, Trachtenberg said his doctor's advice was "what I was planning to do anyway. He said, 'Just go very easy. Stay within a very easy comfort zone," – the same strategy that allowed him to complete his marathon debut at 16.

"Yeah, but back then," he says, "the 7:30 pace was comfortable. Now what's comfortable is 10-minute miles."

But hey, he's still running.

"Within one to three years I'll need a heart valve. I'll come back and run the 55th New York City Marathon faster because I'll have a valve that opens all the way," he jokes. "Then I'll break four hours."

A sobering thought. For now, there are memories to carry and history to make.

If Trachtenberg once again finishes the NYC marathon, he will be the only man in history to endure both the first and the 50th running of what has become the world's largest marathon, with a record 53,627 finishers in 2019, the last time it was held.

And at the finish, he might see his old Princeton teammate who spent 48 years racing nearly 4,000 miles and, even now, still runs in his dreams.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.