Caption

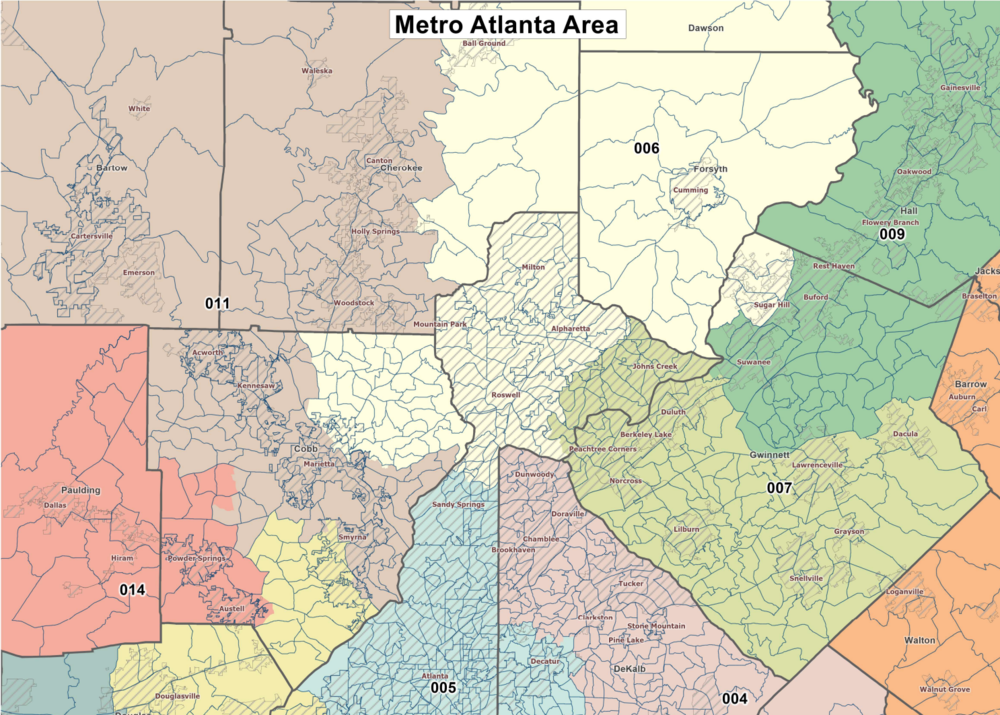

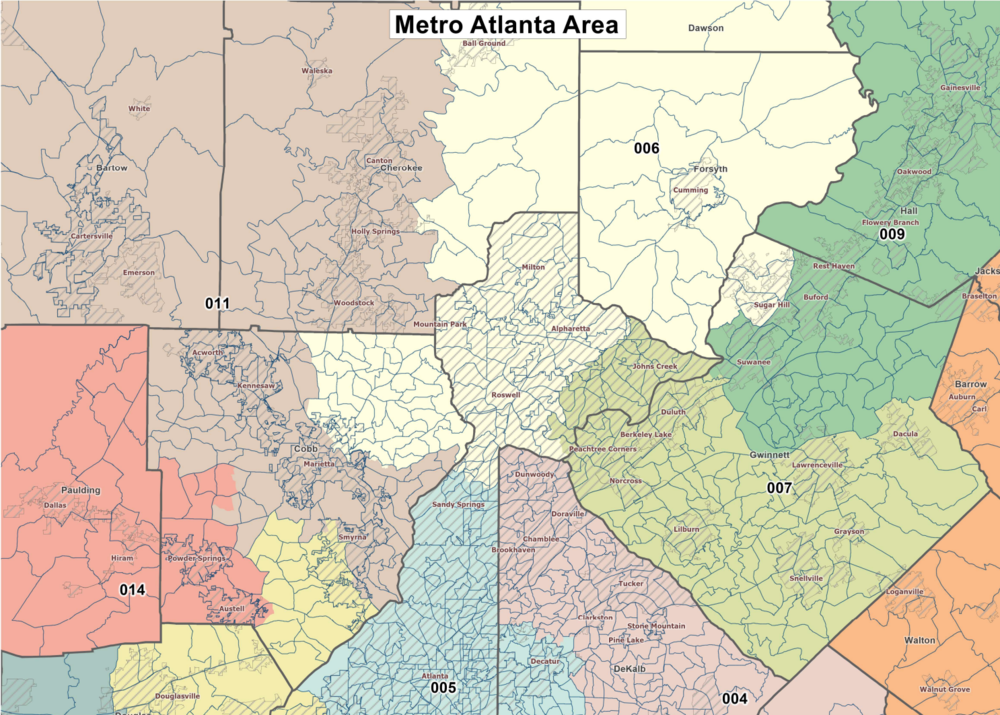

The likely new Congressional map in Georgia drastically alters the boundaries and partisan makeup of the 6th Congressional district.

The likely new Congressional map in Georgia drastically alters the boundaries and partisan makeup of the 6th Congressional district.

Georgia is one step closer to a new congressional redistricting map that bucks political and demographic trends to give Republicans another seat in the delegation.

With a 96-68 vote, the Georgia House voted Monday to send the GOP-backed proposal to Gov. Brian Kemp before the end of the special session.

The new map removes Democratic precincts in DeKalb County from Georgia's 6th Congressional District and adds in heavily conservative parts of Cherokee County, all of Forsyth County and Dawson County, stretching the formerly suburban seat nearly 80 miles north of Atlanta and making it all but impossible for incumbent Rep. Lucy McBath to win.

The neighboring 7th District's geographical footprint shrinks to include part of Gwinnett County and parts of Johns Creek to create a Democrat-dominated seat. That will likely see incumbent Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux face a primary challenge, as McBath announced she will be running in the new 7th District.

The law does not require U.S. House representatives to live in the district they represent, and current 9th District Rep. Andrew Clyde, a Republican, is also drawn out of his current seat and into the newly vacant 10th District.

This year's redistricting process is the first time that the federal government does not have to pre-clear changes in Georgia and other jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory changes, but Republicans contend their proposals still comply with the law.

"We don't draw maps to protect incumbents — an individual who happens to be sitting in the seat," House redistricting chair Rep. Bonnie Rich (R-Suwanee) said. "We draw maps for the people or the voters or the districts."

Overall, the new boundaries are likely to elect nine Republicans and five Democrats, while eight Republicans and six Democrats were elected in 2020.

Democrats, nonpartisan redistricting groups and voting rights advocates have objected to the GOP-dominated mapmaking process, arguing that Georgia's new political boundaries violate the Voting Rights Act and were not created in an open and fair manner.

Rep. Matthew Wilson (D-Brookhaven), who is running for insurance commissioner, citing the lack of public town hall meetings in many of the state's most populous communities, said Monday that Republicans' claim of a transparent process "is tantamount to lipstick on a pig."

"Now we have the map, and we can juxtapose the end result with the words we heard all summer and into the fall," Wilson said. "And the truth now is quite clear. You've been saying one thing — but doing another."

Georgia has grown by more than 1 million people in the last decade, almost entirely via a surge of Black, Asian and Hispanic people flocking to Atlanta and its surrounding counties. The new map does not add a new majority-minority congressional district, even as the state is on track to be a majority-nonwhite state, if not already.

Boundary lines for the state House and state Senate passed during the special session will create additional districts that will favor Democrats, but the minority party objects to where and how those seats are drawn. Lawsuits over all three maps are all but certain once the governor signs them into law.

"The majority party had an opportunity — indeed, an obligation — to implement a fair and transparent participant process to work across party lines on maps that are equitable for all Georgians," Minority Leader James Beverly (D-Macon) said. "Instead, they chose the process of closed doors, locked gates, closed processes to deter participation in the democratic process."

House Speaker Pro Tem Jan Jones (R-Milton) said changes to specific congressional districts cannot be viewed in a vacuum, noting each new boundary "is a piece of a large, complicated and changing population puzzle."

"That puzzle, the state of Georgia, has seen shifts in population growth that drove changes in congressional maps rippling east, west, north and south," she said. "And yes, the 6th was short by a mere 657 persons, but the districts touching it and those not touching it required movements that the 6th and all other 13 congressional districts cannot escape."