Caption

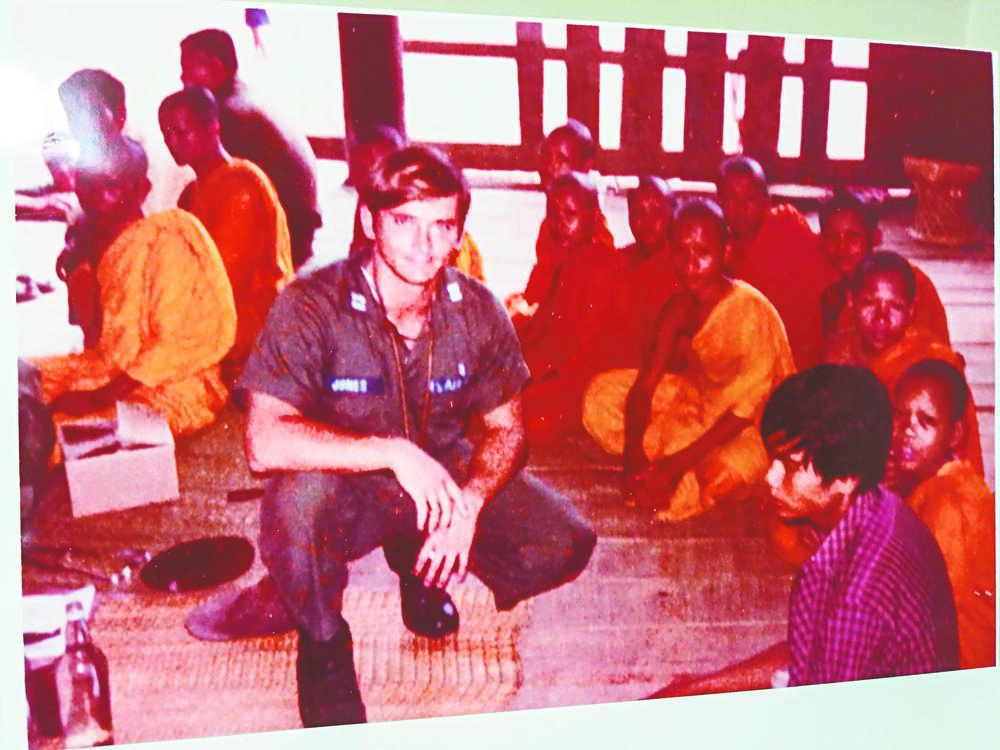

In this 1972 photo, U.S. Air Force Maj. Bobby Jones is shown helping local villagers with their medical issues as a doctor working out of Udorn Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand.

Credit: Contributed photo

In this 1972 photo, U.S. Air Force Maj. Bobby Jones is shown helping local villagers with their medical issues as a doctor working out of Udorn Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand.

By Mark Millican

Special to the Daily Citizen-News

The pilot’s instructions were both explicit and alarming: “You see that guy right there? Go straight to him, because if you don’t you’ll be chopped up by the helicopter blades!”

The small helicopter Jo Anne Shirley of Dalton was flying in had just landed at an awkward angle halfway up Bach Ma Mountain in South Vietnam, where an F-4D Phantom jet crashed during a medical mission decades earlier. They were looking for any trace of the aircraft that went down on Nov. 28, 1972, or her brother who was aboard, U.S. Air Force Maj. Bobby Marvin Jones.

“I thought right then, this is crazy! What is a housewife from Georgia doing here?” Shirley said recently. “Then they had to come back and get us in the same way. For someone like me, it was an amazing experience.”

Initially, Jones, a native of Macon, was reported as missing, but was ultimately declared dead on the same day the flight disappeared, military records state. His body has never been recovered, but Shirley has not given up hope of finding him. On the day of the 36th anniversary of the crash, the family received a “blood chit” from the Air Force that Jones carried. It’s tangible evidence Bach Ma Mountain may be his final resting place.

Jones was deployed with the 7th Air Force, 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing of the 432nd USAF Hospital.

“On Nov. 28, 1972, he was a passenger in a McDonnell-Douglas Phantom II fighter (F-4D) on an administrative flight from Udorn (Thailand) to Da Nang, South Vietnam. About 18 miles from Da Nang, radio contact with the aircraft was lost. His remains were not recovered,” according to honorstates.org.

“He was two years older than me, a great guy, and we just had a real close relationship,” Shirley said. “We were both at the University of Georgia; the older we got, the closer our relationship got. It was wonderful.”

After medical training at the Medical College of Georgia and an internship in Dallas, Texas, Bobby Jones, M.D., enlisted in the Air Force and was sent to Thailand’s Udorn Royal Thai Air Base in September 1972 as a flight surgeon caring for Air Force personnel.

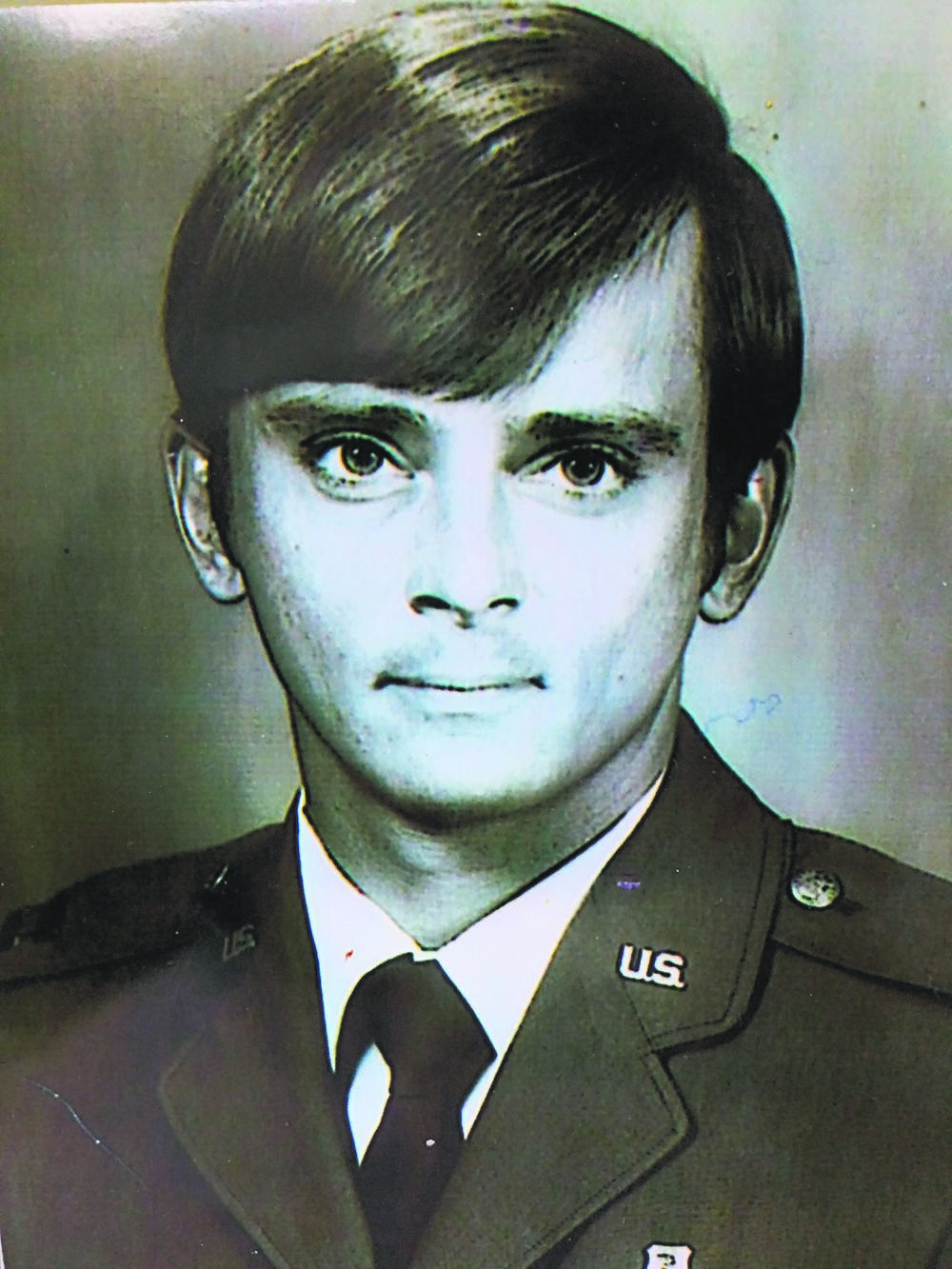

U.S. Air Force Maj. Bobby Jones

“He had to log flight time even though he wasn’t a pilot,” Shirley said. “One of his best friends was a flight surgeon in Da Nang, and so on Nov. 28 they were going to take supplies from Udorn into Da Nang, unload everything — and we don’t know if they were going to load some other stuff up and bring it back to Udorn — but he decided he would go. They went in an F-4D (Phantom) two-seater, so he was sitting in the back seat because he obviously wasn’t a pilot. They were going to fly in and do that and come back.”

She added it is unknown whether the plane was hit by enemy fire, if weather contributed to the crash or if it was pilot error — or a combination. Bach Ma Mountain is more than 4,700 feet in elevation, and Shirley said she was told the Phantom clipped the top of the mountain. Thus began a mystery that is still unsolved 49 years later.

The Jones and Shirley families soon learned of a group called the National League of POW/MIA Families.

“For about 40 years I’ve been the Georgia state coordinator,” said Shirley. “My mom and dad found out about the National League within a year after Bobby became missing ... We had no idea what that organization was, but it sounded like you were going to be there with other people who were going through what you were going through. And hopefully you’d get an update on your case.”

For around 18 years she also served on the League board of directors, 16 years as chair. During that time, Shirley also participated in four delegation trips to Thailand and Vietnam.

“You learn very quickly that, yes, it is about your loved one, but it’s also about all of our guys who are missing or unaccounted for,” she explained. “You begin to meet other family members and get close relationships with a lot of them. It was very interesting, and a real challenge.”

Two people she toured with were Ann Mills-Griffiths, who also had a brother missing, and Dick Childress, a Vietnam veteran and the No. 2 leader in the National Security Council in the Reagan Administration who became involved in the National League. They met with high-ranking government officials in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand.

“They knew Ann and Dick, but they’d look at me like ‘Who is that?’ and ‘What’s she doing here?’ As I went each time, it became a little more of them knowing who I was and why I was there,” Shirley recalled. “I was there to represent the families; Ann represents the organization and Childress represents everything. So it was really quite an experience for me. We would meet those high-ranking officials and then fly out in a helicopter to wherever they were doing excavations (where aircraft had gone down), in the middle of nowhere mostly. Most of the time we’d eat in a tent, sleep in a tent, bathe in a tent, we’d be there for several days.”

During one trip there was a “moving, emotional with tears flowing” ceremony she was part of when the remains of U.S. servicemen were found. Her most recent trip was a half-dozen years ago with her husband, Rudy, who was in medical school with Bobby Jones years earlier.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (dpaa.mil) is a bureau of the U.S. Department of Defense. It is headquartered in Hawaii and responsible for sending excavation teams into Southeast Asian countries involved in the Vietnam War.

“I’ve made close relationships with a lot of them,” Shirley said of personnel there. “A number of years went by, and they went back to decide if they wanted to excavate that (Bach Ma) mountain slope. So they went to the very bottom of it and didn’t find anything — they found a handful of airplane debris and that was it. They were thinking that if they’d clipped the top, after all those years it would wash down. They didn’t find hardly anything.”

However, several years later in 2007 a team returned to survey the central part of the mountain. They found a “blood chit” sitting in the root of a tree.

“I had no idea what a blood chit was; it’s a piece of heavy silk fabric — about a foot wide and two feet long — and it has a message in English at the top, and in Vietnamese, Laotian, Cambodian, Chinese and any (language) in that area — it’s translated (to whomever finds it). At the bottom, on the right hand side, it has a very small red number,” said Shirley.

The chit went inside a pilot or passenger’s flight vest, and the name or number went into a database. The chit would be turned in upon completion of a successful flight to be used again, but if the flight went down the number stayed correlated to the person’s disappearance.

“So they find the blood chit, and that number is barely visible,” she continued. “It was so exposed to their vision; it wasn’t covered in dirt or debris or leaves or anything. When they took it back to the lab in Hawaii, they called me and told me they’d found this blood chit — and it was the one Bobby had in his flight vest that day.”

The chit was fragile and therefore carefully opened to minimize further damage, having been exposed for decades to the soil and high humidity. The chit was sent to the Department of Mortuary Affairs, and a technician Shirley knew there said it had to be logged into the system. But he called back the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, and the chit was delivered to the family on the day after the holiday on Nov. 28, 2008, by special delivery — the exact day of the flight going down 36 years earlier.

“My kids were home, my parents were there, and we were able to open it up together for the first time,” Shirley remembered. “I took it and had it framed so people can’t touch it because it’s kinda fragile if you touch the edges.

“When I got it, I thought this might be the only thing I ever have. They went back into that central part of the mountain and excavated (where the chit was), and found no remains. They went back in a couple of years to the upper part, and didn’t find any remains. Now they’ve decided they should’ve expanded it more than they did. They were going back this year on Aug. 1 to Sept. 30 and expand the search to both sides. They had to cancel it because of the coronavirus.”

Shirley is reflective about the possibility of finding something more of her brother.

“Will I ever get my brother back? I don’t know,” she pondered. “But honestly, I’ve just turned it over to the good Lord … (Capt.) Jack Harvey was the pilot. It’s not just about Bobby, it’s about both of them. This Nov. 28 will be 49 years I haven’t had my brother, so it’s been quite a journey along the way. Getting involved I’ve had some real close relationships with people who have really worked these cases.

“I’ve actually flown over Bach Ma Mountain three times on the way out to another site, and when the (pilot) up front was told that my brother went down at the top they made a little U-turn and went back. A couple of times there were clouds at the top. (The League) has told me in 2022 they’re going back out to do that expansion.”

Shirley was asked if finding her brother’s remains has become a life mission.

“It has, and even though I know I might not get him back — and there are times when I feel like they’re not going back out to his site — and I understand that because they have so many others that they’ve got to go do,” she replied. “I just pray for him every day, lift him up to the good Lord and say, ‘I hope he’s up there with you and my mom and dad,’ and I hope that at some point I’ll be able to bring him back.”

Ann Mills-Griffiths is the current chair of the National League of POW/MIA Families board of directors, and was asked about a potential trip to Bach Ma Mountain in 2022.

“They have a team in Vietnam as we speak doing investigations, and it’s a joint team between U.S. and Vietnamese investigators,” she said from their headquarters outside Washington, D.C. “We have worked on training Vietnamese personnel to be able to conduct unilateral recoveries, especially in sensitive areas where they much prefer there be no Americans running around. I know Bobby Marvin Jones is a high priority to our team of DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency) specialists, the Stony Beach team.”

The fragmentary remains of Griffiths’ brother, U.S. Navy Commander James B. Mills, were found when a Vietnamese fisherman’s net snagged on the wreckage of an F-4D Phantom off the coast of North Vietnam. He was serving as a radar intercept officer on the jet.

Dick Childress is a Korean War veteran who was deployed as a province-level civil affairs adviser in Vietnam. His training included going to language school and earning a graduate degree in Asian studies, and his mission included living with the Vietnamese during the war. He characterized the National League as “simply a unique organization in this country.”

“It’s led by a small cadre of elected leaders, but also serving all the families of those that are missing in action or KIA/DNR (killed in action/did not return),” he began. “They’ve gone through (presidential) administration after administration. Some (U.S. presidents) tried to write it off, tried to avoid it.

“I went to the National Security Council when Reagan was the hero of this (League), and I wrote the original strategy that opened up the warehouse where they’re (Department of Defense) storing remains, and had some archives opened and started the joint crash site excavations.”

Childress noticed while he was in “partnership” with the League, President Ronald Reagan “loved them and had them in there to see him two or three times — plus the national security advisers.”

“At the White House level, when you get bureaucratic incompetence you can intervene (and say), ‘This is the White House calling …’ and get problems straightened out pretty quickly,” he revealed. “Those days are gone. Now we’ve got a tremendous amount of resources, (such as) personnel. We’ve entered a new relationship with Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, which has helped account for people too. But we still have major challenges — our own internal agencies’ bureaucratic (red tape), and we’re watching carefully our state-to-state relations (in an international sense) with all three countries, that they don’t interfere and that we can keep it separate and humanitarian as we started the thing.”

Childress said Jo Anne Shirley came to the League “at one of the critical times.”

“I dealt with her closely and spoke at every League meeting,” he said. “I took many trips over there as a government official, and started going with the League on their trips. (The League) is fulfilling the pledge that we troops on the ground couldn’t always do while we were in combat — leave no man behind. Well, they’re not leaving their men behind …

“I got very close to the League, not just because I’m a Vietnam veteran but because I believe in the mission and the importance of it nationally and for active-duty troops, for veterans, for millions of Americans. We, in fact, care for our missing and pull out all stops to get them returned, alive or dead. At least, give answers to the families why neither is possible.”

Childress was asked about another trip to search for Maj. Jones.

“That’s my understanding,” he confirmed. “They’ve recovered some more information that may lead to another investigative trip, to finish it up. You have to do that sometimes. We’ve gone to some (search for remains) cases four or five times. And if you get new information from the archives or a new analyst who looks it over or other intelligence, you build more leads.

“When we started, it was like bread crumbs, picking them up at Stony Beach — our intelligence operation at that time — the data, and as we picked them up they eventually turned into loaves of bread that I could take to the Vietnamese politburo in my negotiations and turn them into things.”

Still, there are bureaucrats who “stand in the way.”

“You just kinda break their back and move on,” Childress said of the League’s indomitable spirit. “My eyes were opened a lot about our government when I was at the National Security Council. It’s not that people are evil, it’s just that they mislead themselves and go into group-think and defend each other instead of looking at the mission. They lose sight of it.”

Childress said he began the military leg of his career in Georgia, in the Army’s 4th of the 61st Artillery, at the former Nike Hercules (missile) site in Byron near Warner Robins Air Force Base.

Maj. Bobby Jones and Capt. Jack Harvey are both listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington, D.C. Jones’ commendations and medals include a Purple Heart, National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Campaign Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Air Force Presidential Unit Citation, Vietnam Gallantry Cross and Air Force Good Conduct Medal.

As of Nov. 19, 2021, the number of Americans missing and unaccounted for from the Vietnam War is 1,584, according to pow-miafamilies.org.