Section Branding

Header Content

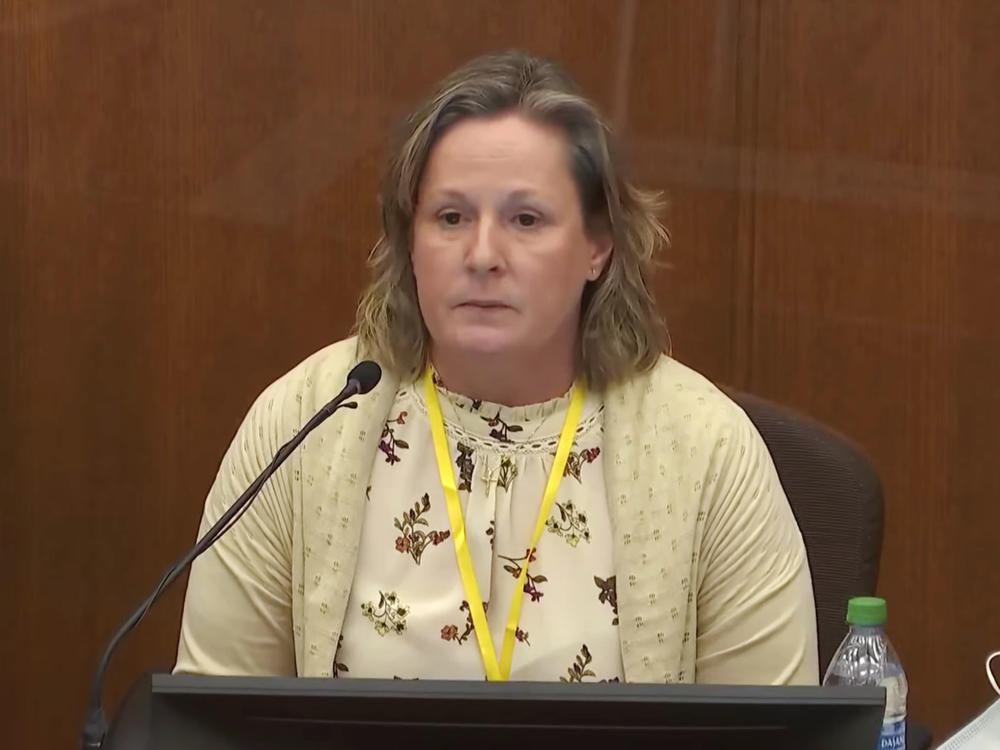

The jury begins deliberations in Kim Potter's trial over the killing of Daunte Wright

Primary Content

Updated December 20, 2021 at 2:28 PM ET

The manslaughter trial of former police officer Kim Potter is now in the hands of the jury after attorneys finished their closing arguments. Potter fatally shot 20-year-old Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in the Minneapolis suburb of Brooklyn Center last April.

"I am certain you realize this case is important and serious and therefore deserves your careful consideration," Judge Regina Chu told the jurors early Monday afternoon. "We will await your verdict."

Potter sobbed as she took the stand on Friday, testifying that she meant to draw her Taser instead of her handgun when she shot Wright. She also said that she was concerned he might be carrying a gun, after discovering that Wright had an arrest warrant linked to a gun charge.

Potter faces two counts: first-degree manslaughter and second-degree manslaughter.

Prosecutors have argued that Potter had been thoroughly trained on the use of a handgun and a Taser, and that her use of the Taser in this situation was inappropriate.

Defense attorneys, meanwhile, have argued that Potter's use of force was appropriate: At the time, fellow officer Sgt. Mychal Johnson was leaning into the passenger side of the car, and they feared Wright might drive off. The shooting of Wright was an accident, the defense said.

The deadly incident touched off days of protests in Brooklyn Center, and occurred while the murder trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin was taking place in nearby Minneapolis.

Prosecutor says Potter should have known the difference between her gun and her Taser

"The defendant told you her sons will be home for the holidays," Erin Eldridge, an assistant attorney general for the state of Minnesota, said as she began her opening statement for the prosecution.

"But you know who won't be home for the holidays is Daunte Wright."

Speaking directly to the jury, Eldridge rehashed arguments prosecutors had made throughout the case. Potter should have known that she had drawn her service weapon, Eldridge said, and Wright's attempt to flee didn't change the fact that Potter fired the lethal shot.

Eldridge emphasized that Potter had had yearly trainings on "weapon confusion" in her 26-year career on the police force, yet she still drew her Glock during the April 11 traffic stop and held it for about five seconds before firing on Wright.

"This was no little oopsie. This was not putting the wrong date on a check. This was not entering the wrong password somewhere. This was a colossal screw up, a blunder of epic proportions," Eldridge said. "It was precisely the thing she had been warned about for years, and she had been trained to prevent it."

Eldridge also criticized an argument made by the defense that Potter fired because she feared that Wright was about to drive away and endanger the life of her fellow officer, Johnson, who was leaning into the passenger door of the car.

"Sergeant Johnson was clearly not afraid of being dragged. He never said he was scared. He didn't say it then, and he didn't testify to it in court," the prosecutor said.

She added that Johnson even shut the passenger door before Wright drove away.

Eldridge urged the jury to set aside their feelings about Potter and apply the law to the two charges she's facing.

Potter didn't cause the shooting and was permitted to use deadly force, defense says

Potter didn't cause the situation that led to Wright's death and her use of deadly force was legal, even if she didn't know she was doing it, defense attorney Earl Gray said in his closing statement.

Gray described the "chaos" of the traffic stop and said Wright's decision to resist arrest and attempt to flee made him responsible for his own death.

"He didn't want to go to jail. He wasn't going to listen to these police officers," Gray told the jury. "That's the cause. Everything before that the police officers did as they were supposed to."

The defense lawyer also recounted the testimony of some witnesses who said that, because Johnson was leaning into the car as Wright prepared to drive away, Potter was justified in using lethal force.

Gray, who described Potter as a "peaceful" and "law-abiding" person, said it would be wrong to send the police force veteran to prison over what he characterized as a mistake.

"A mistake is not a crime. It just isn't. It just isn't in our freedom-loving country that we're going to put you in jail for a mistake you made," he said.

A person in Minnesota is guilty of first-degree manslaughter if they cause someone's death while also committing a misdemeanor — in this case, the reckless handling of a firearm. For second-degree manslaughter, prosecutors must only show that the defendant showed "culpable negligence" in taking actions that created an "unreasonable risk" of causing death or great bodily harm.

On rebuttal, prosecutors say Potter didn't believe deadly force was justified

During his rebuttal, Minnesota assistant attorney general Matthew Frank recounted that in body camera footage of the moments after the shooting, Potter expressed shock that she shot Wright and said she thought she was going to go to prison for it.

Frank says those actions show that Potter didn't believe that the use of lethal force was justified, as the defense had argued in the case.

"Is that the reaction of somebody who thought deadly force was really necessary?"

Frank also told the jurors that making a mistake is not a defense to breaking the law.

Judge denies a defense motion for a mistrial

After Chu sent the jury away to begin deliberations, both Gray and fellow defense attorney Paul Engh rose to request a mistrial.

Engh argued that Frank read from pre-written notes in his rebuttal and went beyond the scope of the defense team's closing arguments, delivering a lengthy rebuttal instead of what should have been a brief argument.

"They sandbagged us," Engh said.

Gray also asked for a mistrial, saying that Frank misstated the law to the jury during his rebuttal.

Chu denied the motion for a mistrial.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.