Section Branding

Header Content

Meet 4 people who worry about CTE, but never played in the NFL

Primary Content

The degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, is mostly seen in professional athletes who play contact sports. But there's also a quiet population of everyday men and women who are afraid they may have the condition: high school and college athletes, military veterans, people who've hit their heads in accidents, even victims of domestic abuse.

NPR interviewed dozens of people who never played a pro sport yet fear they could have the disease — and because it has no cure and can be diagnosed only with an autopsy, they are simply left to wonder and worry.

Here are some of their stories.

Leo Perez: "I knew there was something wrong"

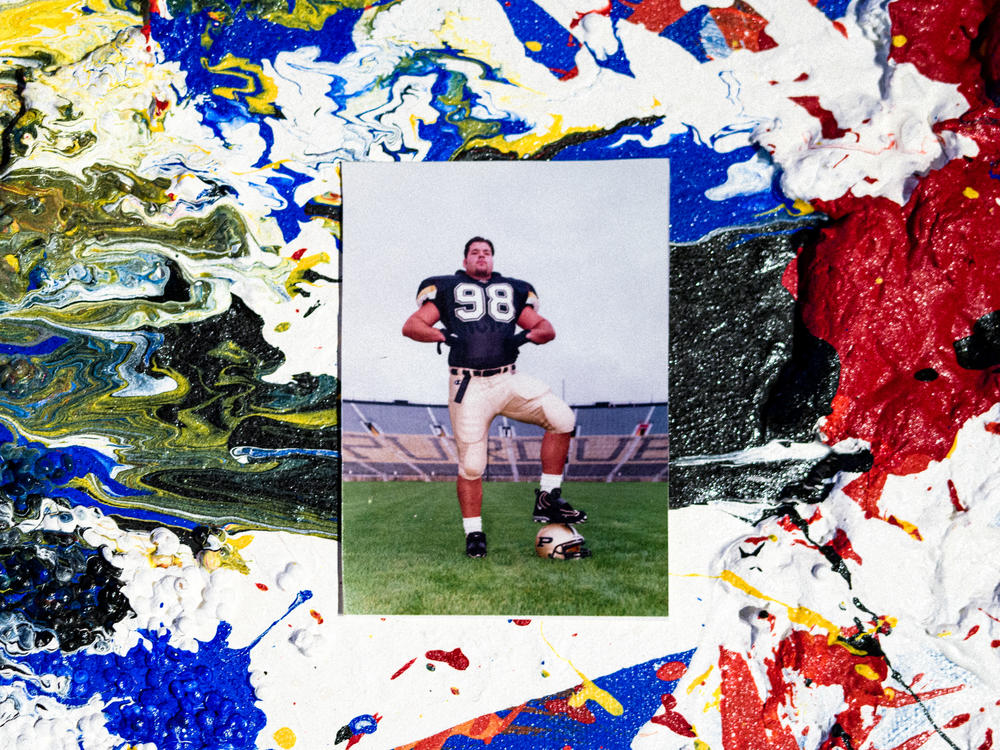

Leo Perez was a multi-sport athlete.

He ran track. He wrestled. And he played football from grade school through college. When he was young, his coaches taught him the art of "spearheading," leading with your skull while tackling and hitting as hard as you can, Perez recalled.

At Division 1 Purdue University in the 1990s, he was a defensive tackle, a position in which "every single play is a concussion," said Perez, 46, who lives in Chicago and works in cybersecurity sales.

One game video shows him so dazed after a helmet-to-helmet collision that he staggered to the opposing team's side and had to be redirected back to his own. But his coaches and trainers brushed off those injuries as just "getting your bell rung," and put him back in the game.

In his late 30s, Perez began experiencing a worrisome constellation of health issues: depression, lethargy, anxiety, light sensitivity, memory loss, ringing in the ears, balance problems. He also struggled with substance abuse and began retreating to "deep, dark places in my mind and dealing with emotions that I've never felt or experienced before," he said.

"I knew there was something wrong," he said, "and that's when I started talking to more and more of my teammates, and more and more people, and realized I wasn't the only one. There's a lot of other people out there, mostly football guys, that were experiencing some of the same thoughts and feelings of anger and sadness."

Like him, they were concerned they were showing symptoms of CTE.

Yet seeking medical help seemed purposeless to Perez because, he said, "What's that going to do? There's no pill, there's no treatment. I know some doctors are prescribing pharmaceuticals, which I'm not interested in."

Instead, Perez began making "massive lifestyle changes from diet and exercise" with the goal of improving his brain health. His pantry is stocked with coconut flour, organic peppercorns, raw almonds, cacao, Korean spice blends, caviar, bone broth, kimchi and other foods he considers nutrition-rich. He also takes collagen and several vitamins, and he meditates.

Perez believes his efforts have made a positive difference. Still, he added, "If doctors went in and opened up my brain right now, I one hundred percent think that I have CTE to some level."

In December 2020, Perez decided to consult with a doctor after all. So he flew to Phoenix, Ariz., for a Mayo Clinic neurological evaluation, reasoning that having a baseline brain exam would let him track any future cognitive decline.

When the results came in, Perez said, he was told he had ataxia, a degenerative disease of the nervous system that usually results from damage to the brain. He now does physical therapy to alleviate his symptoms.

As for whether an autopsy will one day reveal CTE in his brain, Perez tries to put that out of his mind.

"Whether it's depression or it's because of life or concussions and CTE, it doesn't really matter to me at this point," he said of his unresolved health questions. "The fact is, there is something wrong and I'm finding a way to change and improve it."

Katie Weatherston: "Knowing won't really do you any good"

In a rink in her hockey gear, Katie Weatherston describes herself as "a tiny player." At just five feet two inches, she was one of the smallest members of the Canadian women's national ice hockey team.

"But I was probably one of the fiercest," she said. "I had that bull-in-a-china-shop mentality. You wouldn't want to get in my way ... I was fearless."

Her skill on the ice won her a gold medal in the 2006 Winter Olympics, but her style of play came with a lot of bodily contact — and eventually injuries. In one game alone, she said, she took several hits to the head yet kept skating, and she now believes she suffered multiple concussions that day.

"It was the worst decision of my life, probably, to go back and play," Weatherston told NPR.

Since retiring from hockey in the late 2000s, Weatherston has been plagued by eye pain, headaches, sensitivity to bright lights and loud noises, memory problems, and mood swings. She believes a bicycle accident in which she hit pavement headfirst worsened her health issues.

To treat those symptoms, she's tried acupuncture, a chiropractor, group therapy for chronic pain, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, yoga and dietary supplements, to name a few.

"It's a money pit," said Weatherston, 38, who lives in Ottawa, Canada, and now teaches hockey. "For the amount of mixed messages I get from one doctor to the next, it's hard to know who to trust and which direction to go."

Weatherston wonders whether her problems may be due to CTE, but she knows the disease can be diagnosed only through an autopsy.

Even if there were a way to diagnose CTE in living people, Weatherston questions what value that would have, since there are no FDA-approved treatments for the disease. "So knowing won't really do you any good, would it?" she said.

For now, Weatherston said, she's focused on treating her symptoms, but "my fear is that I'm constantly going to keep going downhill."

She added: "No one has ever asked me if I wanted to pledge my brain after I die, but they're welcome to contact me, because I would 100 percent donate my brain to science."

Tommy Edwards: "There's a ton of guys who are scared to death of it"

In high school, his nickname was "Touchdown Tommy."

Tommy Edwards, 47, earned that moniker due to his prowess on the football field. He was a star player at Radford High School in Radford, Va., and later at Virginia Tech and Boise State University. He describes himself as having been a "vicious" player.

Now, Edwards suspects that football, as well as a skull fracture from a skateboarding accident, damaged his brain. For much of his adult life, he has struggled with depression, anxiety, suicidal thinking, substance abuse, and what he calls "brain fog." He also had a nervous breakdown and has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

"Now that I'm screwed up, it's easier for people to say, 'Oh, he's just crazy,'" Edwards said. But he believes he knows the root cause of his problems: "I think I have symptoms of mental illness caused by CTE," he told NPR.

He has consulted with numerous doctors for evaluation and treatment, with minimal success at easing his symptoms. He has even considered building a hyperbaric oxygen chamber for at-home hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which is promoted by some professional football players as helping them recover from concussions.

Edwards continues to try proposed remedies — despite there being no FDA-approved treatments for CTE — because the disease can be so devastating that "if somebody said this witch doctor will cure you," he said, "there would be people lining up to the witch doctor just because of the hope. Just the hope."

Edwards often speaks with others who suspect that they, too, have CTE.

"People only see it as a problem with NFL players." he said, "but, believe me, there's a ton of guys who are scared to death of it."

Shannon Mocca: "When I knew I wasn't crazy, my whole life changed"

Beginning in high school, Shannon Mocca's health began to decline. Confusion. Dizziness. Headaches. Blurry vision. Slurred speech. Sleeping and memory problems. Aggression. Anxiety. Paranoia. Eventually, suicidal thinking and drug dependence.

"I felt out of control," Mocca said in a 2019 interview with NPR from his home in Rapid City, S.D.

In his early 20s, he went to a doctor who diagnosed him with depression and "put me on drugs," Mocca recalled. That was the start of a two-decade-long journey of visiting different medical specialists and trying different prescription medications, all with little result.

"My whole life, they sent me to psychiatrists and psychologists," Mocca said. "I would go to the doctor once or twice a month saying, 'Something's wrong,' and they would give me more drugs. I think I was on nine drugs at one time."

Over the years, he lost his job, got divorced, and cycled in and out of rehab centers for drug and alcohol use. He was also diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Then, in his early 40s, he met with a new doctor who, for the first time, gave him a likely prognosis that seemed to explain his problems: CTE.

That made sense, Mocca said, because he played football in the 1970s and '80s — from a young child through high school — and his style of play was brutal. "I used my head as a weapon," he said. "A lot of people did at that time. Back then it was all violence. There were no rules."

His skull took a battering, including several concussions, one of which knocked him unconscious, Mocca told NPR. He said he also suffered concussions in a car accident and when his head hit a concrete wall while he was horsing around with a friend.

Mocca said he "felt validation" after being told he had the disease. "When I knew I wasn't crazy, my whole life changed — totally changed," he said. "Just felt better, like a big monkey off your back."

He added: "Now that I know that's what I'm living with, I'm not ashamed anymore or thinking I'm crazy."

In 2015, a judge confirmed Mocca's eligibility for disability payments, writing in a decision reviewed by NPR that "medically acceptable evidence, including signs, symptoms and laboratory findings" shows he suffered from CTE — even though the disease can officially be diagnosed only through an autopsy.

In April 2021, Mocca died at age 49 at his home in Rapid City. His brother, Jason Mocca of Battle Ground, Wash., told NPR that the cause of death has not yet been determined, but may have been a heart attack. Mocca's family donated his brain to researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, which in November 2021 said it had found evidence of CTE in his brain.

Jason Mocca called that finding "comforting, in a way, because it's very validating."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.