Section Branding

Header Content

4 of the biggest archeological advancements of 2021 — including one 'game changer'

Primary Content

Global lockdowns and political strife made it a tough year for archaeologists, at least in terms of getting out there on excavation sites.

But despite what many might think, archaeology isn't just about sifting through soil in search of lost artifacts.

A lot of the work actually happens far away from the dig site, in labs where scientists are analyzing these found objects, trying to piece together humankind's unrecorded history.

So while archaeologists spent less time out digging, 2021 was still a good year in archaeology.

We take a look at some of the biggest advancements in archaeology from this year. We spoke to the Trowelblazers, a group of four female archaeologists of different specialties dedicated to highlighting the historic and integral roll of women in the "digging sciences".

They told us what they thought were some of the most important developments in their field in 2021.

Neanderthals may have been more human than we think

Dr. Rebecca Wragg Sykes is an archaeologist who specializes in Neanderthals, a relative of modern humans that went extinct about 40,000 years ago.

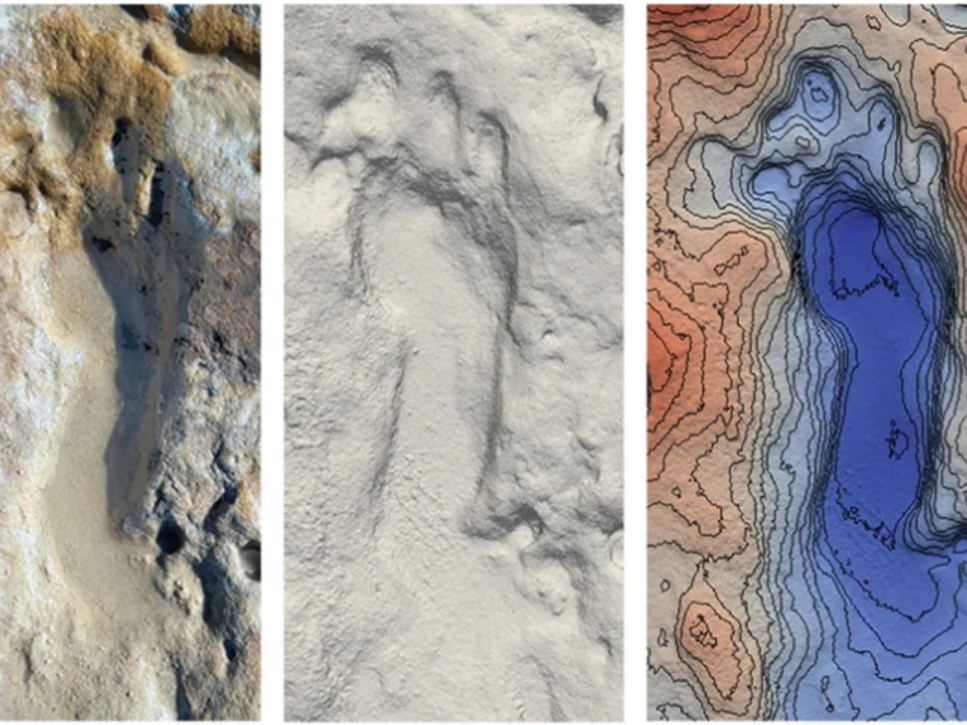

She chose to highlight a paper published last April in the journal Scientific Reports about the discovery of 100,000-year-old Neanderthal footprints on a coastal area of the Spanish Iberian peninsula.

While these aren't the first Neanderthal footprints to be discovered, they are very special.

"This is especially nice, because it's a group - mixed age, including children, some of which are quite young. They seem to be sort of foraging around on the edge of a lagoon," Wragg Sykes said.

The diversity in age is key here and actually helps to challenge a common assumption that Neanderthals foraged in solitude, with the adults peeling off from the group to find food for the children.

The discovery instead gives support to the theory that hunting and gathering might have been a family affair, involving a collaborative and intergenerational effort.

Adorably, the paper also noted that some of the footprints which belonged to children were "grouped in a chaotic arrangement," as if they were playing.

"That's an angle on the Neanderthal life that we don't often get to see," Wragg Sykes said, adding that the discovery helps give a sense of humanity to this not-so-distant human relative.

The powerful women of ancient Spain

Dr. Brenna Hasset is a biological archaeologist who describes her specialty as fascinating and exciting, while also a bit macabre.

"My job is essentially digging up dead people. So I study the lives of people in the past, to try and understand how they lived, how they died."

This year, Hasset was most excited by a paper published in the journal Antiquity about a 3,700-year-old grave site found in Spain. One tomb at the site held the remains of a man and a woman, in addition to a number of personal belongings.

The excavators found that the woman's remains were adorned with a number of precious objects, such as bracelets, necklaces, and a silver diadem, or crown.

Hasset notes that a lot can be learned about someone's role in society by the things they're buried with. The presence of such precious objects suggests that the woman held a high social status and perhaps even political power.

"We always think of these societies being run by sort of manly men, and their pointy objects to enforce power," Hasset said. "When we see these women with these exceptional artifacts, are we actually seeing signs of a type of women's power?"

The million-year-old mammoth

Dr. Victoria Herridge isn't exactly an archaeologist, she's actually a paleontologist who specializes in ancient elephant species.

She chose to highlight a paper published in Nature last February that reported the successful sequencing of DNA retrieved from mammoth teeth found in permafrost in Siberia. The DNA is more than a million years old and is the oldest DNA to ever be successfully sequenced. The discovery challenges the previously held theory that there was only one mammoth species in Siberia at the time, instead showing multiple genetic lineages. The researchers spoke with NPR's All Things Considered last February.

However, for Herridge, it was the age of the DNA that got her most excited, which has broad implications for paleontology, archaeology and a number of adjacent fields, she said.

"To me, it's just like a proper game changer!"

Herridge said this DNA was especially valuable because the last million years were a key period for understanding the course of mammal evolution.

She points out that while the cold conditions of the permafrost helped preserve the DNA, the sheer age of the samples is groundbreaking nonetheless.

"It shows that you can get genetic information way, way, way further back in time that we previously thought was possible."

Herridge made sure to highlight one of the paper co-authors, Patrícia Pečnerová, whose ingenious lab techniques made sequencing the DNA possible.

"I think it shows that the things that maybe were previously dismissed as being impossible may not be impossible. And so maybe we shouldn't rule out the chances with decent, careful lab work and developing techniques."

How to not lose track of our tracks

Dr. Suzanne Pilaar Birch is an associate professor of archaeology and geography at the University of Georgia in Athens.

She chose to feature a paper published recently in Nature about a renewed analysis of footprints discovered in the 1970s in Tanzania. Researchers returned to the site and upon reexamination determined that the tracks belonged to an early hominin species, not to an animal species like a bear, as was previously thought.

The prints, which are an estimated 3.6 million years old, are the oldest evidence of bipedal locomotion of a human ancestor. NPR's Nell Greenfieldboyce covered these findings earlier this month.

However, Pilaar Birch highlighted this story not because of its extraordinary findings, but rather for how it highlights the need for better preservation of our archaeological assets.

"This was work that was done 50 years ago," Pilaar Birch said, "[But] the casts that had been made from this trackway had actually been lost."

She notes that if the casts had been properly taken care of, it may not have been necessary to go back to the site and that we might have been able to draw this important conclusion earlier.

Pilaar Birch said there was a great need to improve long-term preservation of archaeological assets and record management.

While many institutions struggle with funding, she said there was a movement to change that, especially in the area of data preservation and aggregation.

"It's definitely an area that we're seeing a lot of advancement and the National Science Foundation is very supportive and funding new database initiatives."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content